Support the author!

«You sit and think that God will punish you»

In 2023, when the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation declared the non-existent “International LGBT Social Movement” an extremist organization, the Russian queer community finally went underground. For distributing any content mentioning LGBT, you can receive a hefty fine or even a criminal case. Stores stopped selling books with stories about same-sex love, online cinemas are deleting series and films with queer characters, and the social network VKontakte blocks search queries about LGBT. Queer people who agreed to talk about ways to preserve their identity under these conditions were forced to hide even for phone interviews—in friends’ apartments, or even in the forest.

This material was prepared by the team of the project “Blue Capybaras“, where mentors work with aspiring journalists.

The names of all the protagonists have been changed at their request for their safety

Without festivals and libraries

Twenty-year-old journalist Katya lives in a large Siberian city. In high school, she realized she liked girls. But Katya is afraid to say this out loud. Her father once remarked, “If my daughter were a lesbian, I would shoot myself.” At school, Katya was bullied for her appearance: seeing a girl with bright red hair, younger students would shout after her, “feminist and LGBT-trash.” In 2024, during the presidential election, Katya went to her old school to vote—and heard the usual insults from the same now older kids.

The young woman says she can’t cope with external homophobia—outside pressure creates feelings of rejection inside:

“An entire state hates me just for who I am.”

Just six years ago, Katya and her friends participated in a cosplay festival at the local state theater. Music played in the city park, participants set up themed stands for their fandom: anime, movies, books. As Katya recalls, many participants displayed queer symbols; someone even wrapped their child in a rainbow flag. “We took photos, had fun. Just a regular festival,” she says. Fifteen-year-old Katya went there in a rainbow-colored costume with a friend. Now they don’t talk: since 2022, Katya’s former friend publicly discusses “traditional” values, calls queer people “filth,” and supports the war in Ukraine. But Katya has maintained good relationships with many friends from the city’s queer community, who used to meet at local theater and library events.

In 2025, the apartments of Katya’s friends from the Siberian queer scene are the only places where they can openly discuss their problems. Festivals where you could come in a rainbow costume are no longer held in their city. Katya is surprised that just a couple of years ago, organizers spent “state money” on such activities—in her opinion, they couldn’t have been unaware that cosplay attracts the LGBTQ community and that local queer teens often spent time in the library. After COVID restrictions on mass gatherings were lifted, the library stopped holding youth events, keeping only children’s activities. Katya never really liked queer clubs and bars, and now it’s become unsafe to visit them due to police raids.

Until 2021, the St. Petersburg queer film festival “Side by Side” systematically spoke about LGBT issues in Russia. The organizers held film screenings not only in St. Petersburg, but also in Moscow, Novosibirsk, Kemerovo, Tomsk, and Perm. In 2020, anti-LGBT activist Timur Bulatov filed a complaint against “LGBT sexual perverts,” the court suspended the festival’s activities for violating the “self-isolation regime,” the website was blocked, and “Side by Side” canceled screenings in theaters. In 2021, the queer film festival was held online. In 2022, the organizers launched a new project, Q-Space, in Estonia and have since held film screenings outside Russia.

Festival spokesperson, journalist, and podcast host of “Queer Talks” Konstantin Kropotkin recalls that before the ban on “LGBT propaganda,” public discussions and book presentations were among the main gathering points for the queer community in Russia. For example, the novel about the relationship between a camp counselor and a pioneer, “Summer in a Pioneer Tie,” became the second most popular among Russians in the first half of 2022. At the end of the year, the book was withdrawn from sale at the request of Alexander Khinshtein—then a State Duma deputy and co-author of the law banning “LGBT propaganda.”

However, censors didn’t catch everything that made it to bookstore shelves, Kropotkin notes. In 2023, at the Non/fiction fair in Moscow, there was a presentation of Hanya Yanagihara’s novel “To Paradise.” The plot is built on an alternative American history of the past three centuries: for example, in the novel’s reality, the United States legalized homosexual relationships at the end of the 19th century. In these conditions, the main character’s grandfather tries to marry off his grandson for convenience. According to Kropotkin, “everyone who needed to bought this novel, but no one like Zakhar Prilepin and his company made a fuss.”

“Everyone looked at me like I was a giraffe”

Dmitry realized he was gay at 14. He decided to look for gay porn online and accidentally downloaded a virus. The repairman who fixed his phone told Dmitry’s father about his browser history. It ended in a family scandal: his dad yelled at him, and his mom suggested seeing a psychologist.

“My parents kind of support me, but weird stereotypes never go away,” says Dima. For example, as a child, his mom encouraged his interest in clothes and bought dolls for him to design outfits for. “I had almost the entire collection of Disney princesses. I still brag about it,” he recalls now, as he prepares to study clothing design. When Dima was six, his mom, under pressure from relatives, threw out the whole collection, telling him that boys don’t play with dolls, but later secretly bought him another one. His parents also banned him from playing the life simulator The Sims, claiming it was “for girls” (in reality, the game is for users of any gender, but in the Russian internet some compare The Sims to playing with dolls).

Dima says that as a teenager, he tried to change his orientation. His mom insisted it was possible. He watched straight sex videos and tried dating a girl, but after a couple of months in a heterosexual relationship, he realized he wasn’t attracted to women. He waited to turn 18 so he could move from his native Kuban to Moscow or St. Petersburg and meet other queer people there.

To deal with psychological trauma, Dima sought professional help. But he never achieved the desired result. A specialist in his hometown explained his interest in the same sex as hereditary. “I have a second cousin who divorced his wife and moved to another country. The psychologist suggested he was gay and that I inherited it,” he says (a genetic analysis of half a million people showed that homosexual orientation and behavior have a genetic basis and are inherited, though no specific gene responsible for homosexuality was identified). A coach Dima later saw claimed the reason for his homosexuality was a bad relationship with his father and suggested fixing his financial situation—which she considered the most important issue.

In high school, after Dima became sure he wasn’t attracted to girls, he found refuge on the internet: watching reality shows like the Kardashians, reading queer blogs, chatting with guys—“doing everything to escape reality.” One of these chats helped Dima accept himself. For the first time, he could openly ask a new acquaintance questions about same-sex relationships: “He was 25, I was 16. I just chatted with him, asked questions.” Offline, Dmitry didn’t tell anyone in his hometown he was gay until he was 18, except for a couple of friends. Because of his not-masculine-enough appearance, he was bullied at school. “But I did dance, so my legs were strong. As soon as they started, I’d kick them in the stomach, and they’d leave me alone,” he adds.

After graduating, Dima signed with a modeling agency in St. Petersburg. At first, his career didn’t take off—over three months, he was offered only one commercial shoot, so he got a job as a sales assistant in a clothing store. He liked that the employer immediately said, “There’s no homophobia in our team. We don’t put anyone down.” Soon, Dmitry was invited to a fashion shoot in Shanghai. “I could go out in a see-through tank top. Passersby looked at me with inspiration,” he recalls. “When I dyed my bangs blonde in my hometown, everyone looked at me like I was a giraffe. It was dangerous to walk around like that.”

In the professional modeling community, Dmitry didn’t have to feel like a “giraffe”: “There it’s 50-50, or maybe 60-40 gays and straights.” But outside photo studios, he doesn’t feel safe. For example, in Kuban, when Dima was walking home after a shoot in a torn sweater, locals yelled at him, “Are you a faggot?”

Film and the censorship scissors

Films and series with queer characters have become commonplace in many countries in recent decades. But not in Russian distribution anymore. In 2025, the publication “Verstka” calculated that out of 71 series with LGBT storylines, only 25 projects were available on “Kinopoisk.” Another 16 series could only be found by direct link, not by searching in the app. The online cinema also cuts scenes involving queer characters.

One of the series removed from the site was the American The L Word about the lives of eight lesbian women. In Russian online distribution, it’s known as “Sex in Another City.” Journalist Katya watched it in 2023 on a pirate site. The plot revolves around election campaigns, divorces, relationships, job searches, friendships, and bar hangouts. “It’s not about homophobia in our scary world. And that really helped me accept myself,” says Katya.

She chooses films where the focus isn’t on the problems of characters because of their orientation: “I like movies about ordinary people, where homosexuality isn’t a separate plot arc, but just part of the character’s biography. Why does there always have to be a huge backstory: how the character realized they’re gay? What a drama! Awful!” One of Katya’s favorite films is “Happiest Season” with Kristen Stewart. It shows the difficulties LGBT characters face in relationships with their parents and each other. Among series, Katya notes the Russian crime drama “Snail Run”: “The main heroines’ relationship is complicated. But not because of homosexuality, but because of complex human characters.”

Streaming platforms are also unhappy with the law, which forces them into self-censorship and competing with pirate sites. Video hosting sites that violate copyright aren’t controlled by Roskomnadzor, so they don’t have to cut scenes or put up warnings.

Before the law banning “LGBT propaganda” was passed, the “Kinopoisk” service published articles about the history of queer cinema, LGBT in Soviet films, and mass culture. In 2021, summing up the year, journalist Konstantin Kropotkin highlighted three Russian films with queer characters. “Compartment No. 6” is about Finnish student Laura’s journey from Moscow to Murmansk. On the way, Laura realizes her crush on Moscow native Irina is unrequited, and she meets the charming worker Lekha. “Day of the Dead” is another road movie, in which a mother tries to accept her son’s homosexuality after his death. The series “Psycho” shows successful Muscovite Artem, who struggles with internalized homophobia and only allows himself to have relationships with men abroad. But even then Kropotkin emphasized: “Of course, something has already been irretrievably lost. For example, the viewer’s pleasure from uncut films, from getting to know the author’s intent untouched by censorship scissors.”

In 2024, the “queer” label from film critics was given to the Russian film “Holidays,” about the relationship between strict deputy principal Maria and young theater club leader Tanya. Journalist Katya recalls how one night she saw a show on Channel One where host Alexander Gordon asked, “Is there a subtext of sexual relations between the heroines in the film?” But the viewer will not find a direct answer in the film itself or in director Anna Kuznetsova’s interviews.

“The ideal framework [for representation] is the maximum amount of the author’s work reaching the audience. If the creators of a film or series decided to tell a story about a queer person, the distributor’s sacred duty is to show the film as it was made. Any cut distorts the author’s meaning and the viewer’s perception. If we talk about positive representation, it should be a person or character who is equal to the world, who is three-dimensional and holographic,” says Konstantin Kropotkin.

Among films whose characters can provide Russian queer viewers with the support, images, and associations they need, the critic points to works by Georgian directors, for example, “Intersection”—in which a history teacher from Batumi searches for her trans niece. Among Russian projects, Kropotkin recalls the fiction film “Bad Daughter” (2020) about a forced coming out to family, “Sasha” (2022) about a schoolgirl who, after moving to another city, is mistaken for a boy by her new friends, and the documentary “Transition Prohibited” (2024) about the lives of transgender people after emigrating to the Netherlands.

A guide to the queer community

On the social network VKontakte, when searching for “LGBT” in the “communities” section, users from Russia get no results without a VPN. The network reports that the request is unacceptable in Russia. But it wasn’t always like this. In 2016, VKontakte became a “guide to the queer community” for collage artist Polina. Back then, you could find communities, fanfics, art, photos, and films on queer topics in the social network.

When Polina was 13, she found the Norwegian series “Skam” in one of these groups and started watching it every day at six in the morning before school. Her favorite season is the third: it tells the story of Isak Valtersen, who falls in love with upperclassman Even. At the same time, Polina began reading fanfiction about the character Thomas Newt from the film “The Maze Runner.” Although Newt is not gay in the film, some viewers paired him with another character and expressed their fantasies through creativity.

As a teenager, Polina didn’t consider her interest in the LGBTQ community as anything serious. “I think when I read gay fanfic, it helped me experience emotions, but not relate them to myself. That’s easier, right?—the artist reflects. When you don’t accept your orientation, you try to put off reflecting on it as long as possible.”

Today, one of Polina’s favorite films with queer characters is “Little Ashes” about the artist Salvador Dalí.

Polina’s apartment shows her interest in creativity: on the shelf is the magazine “Dialogues about Art,” and her own collages in frames. A bouquet of roses in a vase—a gift from Polina’s girlfriend. According to the collage artist, her relationship with her partner helped her fully accept herself. Polina also tries to choose supportive friends and read independent publications that write about LGBTQ issues.

The only question she still has: will her family accept her bisexuality? “My father will be furious. If he doesn’t accept it, it will be a big blow for me,” says Polina.

A safe space for escapism

What can Russian queer people do who are used to finding like-minded people on social networks? Tonya from Siberia realized she liked girls at 14—she attended a humanities school known as “the place where all the LGBT kids study.” At that time, she had a VKontakte public page where she posted fanfics about same-sex relationships. On this social network, Tonya also met her ex-girlfriend, as well as a friend she now lives with in St. Petersburg.

Tonya considers the viewers of the show “Improv” on TNT to be one of the queerest fan communities. Users of X (formerly Twitter), as well as fanfic authors and readers, fantasized that hosts Anton Shastun and Arseny Popov were in a romantic relationship. She herself says the story she grew up on was the series “Supernatural.” One of her favorite characters in this dark fantasy is the demon hunter Dean Winchester.

- It’s cool when there’s a character who isn’t written as queer, but there’s something about them. Representation in movies is often crappy. No one acts like that in real life. In the media, many queer people are open, they have same-sex relationships. I watch and think, “Well, damn, I’ll never have that.” And that’s why I find characters who look like they’re still in the closet—still at the stage of acceptance. They’re just like me, Tonya says.

The romantic relationship between “Supernatural” characters Dean and Castiel is hinted at in their lines in the series: for example, Dean says Castiel is his family. The creators never confirmed that Dean and Castiel are a couple, so some viewers accuse them of queerbaiting.

At 24, Tonya doesn’t believe she’ll ever fully accept her orientation. Her parents constantly ask if she has a boyfriend. She’s afraid of her relatives, so she doesn’t even consider coming out: in her religious family, it’s believed that “God doesn’t like any of that [queer people].” Although Tonya used to watch “Bohemian Rhapsody”—the 2018 musical about Queen frontman Freddie Mercury—with her family. Back then, the elders were ready to accept the idea that “gays can be good people,” even if they look comical, she thinks. “The bar for representation was extremely low, but at least people knew that gays existed,” she recalls.

After the ban on “LGBT propaganda” in Russia, Tonya’s relatives started saying that queer people should be isolated from society. Now she often thinks about the sinfulness of loving someone of the same sex:

“God said you have to kill gays. But God forgives everything because He loves you—He created you in His own image. So what’s the problem? But you still sit and think that God will punish you.”

The virtual world helps Tonya distract herself from dark thoughts. In 2022, she closed her VKontakte public page and now watches queer content on TikTok, discussing what she sees on X: “You go on Twitter and someone drew fan art of your guys [gay characters]—and you think, ‘Oh, how nice.’” Tonya divides Russian-speaking queer users of X into activist and fandom communities. She admits she doesn’t have the strength to change anything, so she sees social networks as a safe space for escapism.

“Basic advice: move to another country”

Semyon grew up in Moscow. At 16, he realized he was attracted to people of his own gender, and closer to 20 he understood himself as a non-binary person. At school, his classmates watched videos of foreign queer bloggers like Troye Sivan, Connor Franta, or gay couple Alex Bertie and Jake Edwards.

During the pandemic, Senya created a YouTube channel where he posted conversations with a friend about gender and orientation. Thanks to this channel, Senya’s father learned about his sexual identity.

- He accepted me on the principle of Fake it till you make it. It was a bit hard and strange for him. At the same time, his political views suggest he’s tolerant of everything, so he tries to act that way, Semyon explains.

In his teen years, Senya shared thoughts about queerness on Twitter, “a separate little world,” and was involved in activism—it gave him support and hope. In 2018, he went to study in the Netherlands for a year, where he realized and accepted his homosexuality and non-binary gender. Returning to Russia, he participated in protests against the exclusion of the opposition from the Moscow City Duma elections: “It was a sudden, uplifting moment. That time made me want to stay in Russia and change life here.” He was also helped by working at a shelter for LGBTQ+ and feminist activists, where they could rest after stressful work.

In 2021, Semyon started studying design and continued to promote feminism. Now he participates in a libertarian feminist project that does human rights work and holds lectures and festivals. However, after graduating with his bachelor’s degree, Semyon plans to listen to his parents and emigrate: “Dad regularly laments and says I’ll be killed or jailed. His basic advice since I was 12: move to another country.”

Psychologist Yulia Nikonorova volunteers at “Vyhod”*—a non-profit organization that helps LGBTQ people from Russia. In her experience, people who feel internalized homophobia lack support from close ones and a space for self-expression. “Most people who contact ‘Vyhod’ from Russia feel trapped. Homosexuality isn’t just a word. Orientation affects appearance and self-expression. Some people are afraid to go outside and put themselves under house arrest. There’s a lot of fear,” Yulia shares. According to her, most of Vyhod’s clients are preparing to emigrate: learning foreign languages and looking for jobs abroad, information about asylum.

Semyon from St. Petersburg plans to apply for a master’s program abroad. Katya, the Siberian journalist, often visits friends in Georgia, where, she says, she can be her true self—and when she returns, she notices how much self-censorship she imposes on herself at home. Because of homophobia, Katya prefers to answer questions about orientation with, “I don’t date guys.” For this publication, she gave an interview via Zoom from a friend’s apartment: at her parents’ home, she’s afraid to talk about her sexual identity out loud, even locked in her room—they might hear. And Dima from Kuban called from the forest. While he prepares to enter a design program, he lives with his parents and doesn’t dare tell them he dreams of leaving Russia and finding love.

Collage artist Polina also wants to live and study in another country—where she can openly express love for her girlfriend: hold hands, kiss, plan a future together. In Russia, all this is impossible for queer people. “These aren’t difficulties, it’s a disaster. And I don’t plan to deal with them,” says Polina. “You don’t have to endure it if there’s even the slightest chance to find an environment where you won’t be stoned for who you are.”

*recognized as foreign agents in the Russian Federation

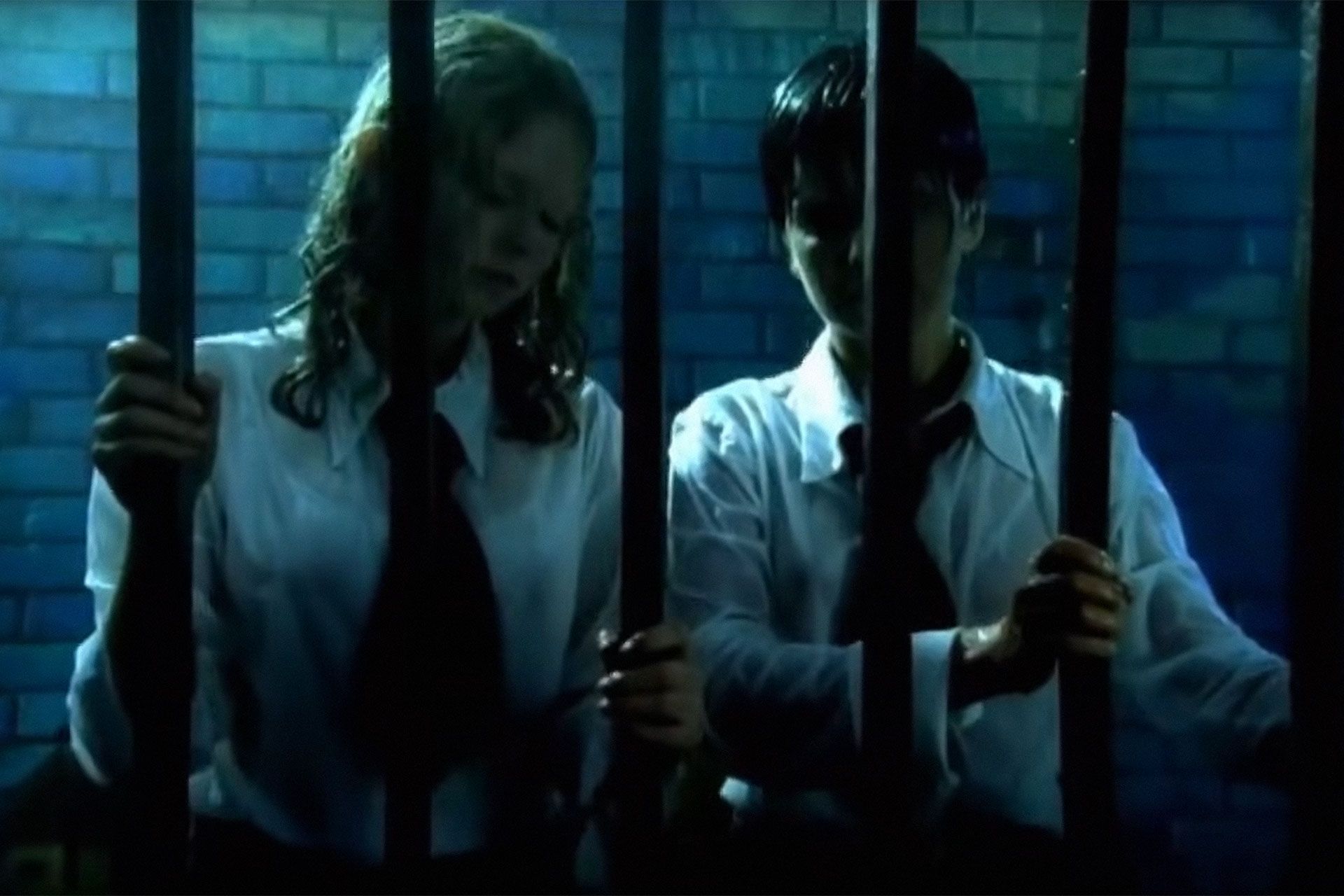

Main photo—a still from the music video for t.a.T.u.’s song “All the Things She Said.” Source: YouTube