Support the author!

Non-Imperial History: The Zaporozhian Cossacks. The Beginning

The history of the formation of the Cossacks in the territories of modern Ukraine and Russia had common features and causes. But there was also one fundamental difference. While in Russia the Cossacks are considered a separate, specific part of the Russian people (although some Cossacks categorically define themselves as a separate ethnic group), in Ukraine they are an integral and, without quotation marks, state-forming part of the Ukrainian nation. So the words of the anthem, “І покажем, що ми, браття, козацького роду” (“And we will show that we, brothers, are of the Cossack lineage”), are not just a beautiful metaphor.

The term “Cossack” is first mentioned in the Codex Cumanicus—a dictionary of the Cuman (Old Kipchak, that is, Polovtsian) language, presumably compiled at the end of the 13th century by Latin missionaries in the territory of the Golden Horde and published in 1303. There, the word “Cossack” is translated as “guard,” “sentry.” And in translations from a number of Turkic languages, the word “Cossack” means “free,” “independent” (thus, the well-known expression “free Cossack” is essentially a tautology).

The fact that the word “Cossack” is most likely of Turkic origin is confirmed not only by the Codex Cumanicus, but also by the fact that, in this meaning, it is the self-designation of one of the major peoples of Central Asia—namely, modern Kazakhs. In fact, Kazakhs have always called themselves “Cossacks,” and their country—not “Kazakhstan,” but “Kazakhstan.” In fact, this name for their country has survived to this day.

In 16th–17th century Russia, including in official documents, the ethnonym Cossack was also used in relation to the Kazakhs. For example, the Russian chronicler of the first half of the 17th century, Savva Yesipov, who appeared in Tobolsk in the 1620s, called the Kazakh Khanate, with which the Siberian Khan Kuchum interacted, the “Cossack Horde.” Likewise—“Kasaccia Horda”—the Kazakh Khanate is labeled on a British world map from 1780.

Russian historian, writer, and ethnographer Alexey Levshin wrote in 1827: “The name ‘Cossack’… belongs to the Kirghiz-Kaisak hordes from the beginning of their existence; they call themselves nothing else.“.

Levshin’s point of view is notable, on the one hand, for his understanding of how the Kazakhs called themselves, and on the other, for reflecting the fact that for almost 200 years, from 1734 to 1925, this people were mistakenly called “Kirghiz-Kaisaks” in Russia.

In 1925, the 5th All-Kazakh Congress of Soviets adopted a decree “On restoring the name ‘Cossacks’ for the Kirghiz nationality.” Up until 1936, the future Kazakh SSR was called the “Kazakh ASSR.” And only then, as part of the major Stalinist turn to the traditional Russian imperial discourse, in the USSR (apparently to distinguish the “truly Russian” Cossacks from one of the Turkic peoples), the terms “Kazakh” and “Kazakhstan” were invented. However, in practice, these terms were used mainly in Russia and/or by Russian-speaking citizens, since even after 1936, Kazakhs themselves continued to call themselves Cossacks, and their republic “Қазақ СССР“

However, when it comes to Cossacks in the generally accepted sense, this term usually refers to the two Slavic ethno-social communities known worldwide—the Ukrainian and Russian Cossacks.

These, in turn, are divided into many other groups (Zaporozhian, Don, Terek, Ural, and several others). Their modern ethnic affiliation is determined primarily by the fact that they all spoke and speak Slavic languages—Russian and Ukrainian, as well as their dialects.

Brodniki from the Wild Field

In the Great Steppe (“Wild Field,” Desht-i-Kipchak)—the forest-steppe zone, on a vast territory from the lower Danube in the west to the Irtysh in the east, from the Black Sea coast in the south to the middle reaches of the Dniester, Dnieper, Don, and Volga—many peoples have coexisted since time immemorial. The Iranian-speaking Cimmerians, Scythians, and Sarmatians of antiquity were displaced in the early Middle Ages by the Huns. Then came the turn of numerous Turkic peoples: Bulgars, Black Hats, Torks, Berendei, Khazars—who remained there likely after the collapse of the Turkic, Avar, and Khazar khaganates, or migrated there later, like the Pechenegs and Kipchaks (Polovtsians).

To a large extent, all these peoples formed the ethnic basis of the future Cossacks. This opinion was held, in particular, by the well-known Soviet historian Lev Gumilev. As the contemporary Russian historian and ethnologist, Doctor of Historical Sciences Alexander Sopov, noted, “L.N. Gumilev, repeatedly emphasizing the origin of the Terek Cossacks from Christian Khazars, generally traces the Cossacks back to baptized Polovtsians.”.

In the 10th century AD, we also find Slavs in the Desht-i-Kipchak. In particular, the fact that Slavs lived on the Don (Tanais) was reported by the 10th-century Arab historian, traveler, and geographer al-Masudi, who visited Khazaria in the first half of that century. There, as wrote history professor Pyotr Golubovsky, many Slavs lived in the 8th–10th centuries.

Another hypothesis about the origin of the Cossacks should also be mentioned. Polish writer and archaeologist Jan Potocki believed that the Cossacks were descendants of the Kasogs, whom Grand Prince of Kiev Mstislav Vladimirovich settled in the 11th century in the Chernihiv region as his guard. The version is not without logic. The point is not only the similarity between the words “Cossacks” and “Kasogs,” but also that the Kasogs are one of the exoethnonyms of the Circassians, who were later called Cherkasy or Cherkasy in Russia and Ukraine.

At the same time, Nikolai Karamzin in his “History of the Russian State” wrote that the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (10th century) called the territory between the Caspian and Black Seas, where the Circassians (Adyghe) lived, “Kazakhia.” In addition, Karamzin notes that the Ossetians still call the Circassians “Kasakhs.”.

It is also notable that the Zaporozhian Cossacks themselves called themselves Cherkasy for quite a long time. At the end of the 14th century, the city of Cherkasy was founded on the Dnieper. Then, as reported in his “History of the Don Army” by Pushkin’s contemporary, Major General and historian Vladimir Bronevsky, Cherkasy, whom he calls Zaporozhian Cossacks, already founded the city of Cherkassk on the Don (now the village of Starocherkasskaya).

In the 12th century, the Brodniki appeared in the Desht-i-Kipchak. In their way of life, they greatly resembled the future Cossacks.

The Brodniki were also free people, united in militarized communities, engaged in fishing, robbery, and periodically hired themselves out as troops or guards to various princes of the former Kievan Rus’ lands, as well as to Polovtsian khans. It is also notable that the Brodniki had neither princes nor khans. Of their rulers, only voivodes are mentioned in the chronicles, which also brings them closer to the Cossacks and their atamans.

The most famous episode involving the Brodniki dates to 1223, during the Battle of the Kalka, where they acted as allies of the Mongols. The Brodniki voivode Ploskynya promised the surrounded Russian princes that the Mongols would not shed their blood and kissed the cross, which clearly characterizes him as a Christian. The Mongols “kept” their word. The surrendered princes were laid under a wooden platform, on which the Mongols sat to feast and dance, crushing their captives to death.

The Brodniki are fairly regularly mentioned in Russian chronicles of the 12th–13th centuries, as well as in reports by foreign authors. Thus, in a letter from Pope Gregory IX from 1227, the phrase “Cumania et Brodnic terra…” (land of the Cumans and Brodniki) appears. That same year, a papal archbishop was appointed to Cumania (the Polovtsian steppe) and the land of the Brodniki. In 1250, Hungarian King Bela IV informed the Pope that the Tatars had captured the eastern neighbors of his kingdom, among whom he listed the Brodniki. In Bela’s message from 1254, Russians and Brodniki are named as tribes of “infidels,” which in the terminology of contemporary Catholics meant “Orthodox.”

The very name “Brodniki” is interpreted by researchers either as “wanderers” or as people living by a ford. Despite a number of reports by medieval authors that allow the conclusion that the Brodniki were Christians, their ethnic affiliation is a subject of scholarly debate.

Thus, Svetlana Pletneva, a specialist on the nomadic peoples of the medieval Black Sea steppes and the forest-steppe zone of Ukraine and Russia, Soviet and Russian historian and archaeologist, and laureate of the USSR State Prize, based, among other things, on the results of her excavations in the Don region, called the Brodniki “the oldest Don Cossacks.” Pletneva considered them descendants of both runaway peasants and townspeople from the northern Russian principalities (in particular, Ryazan), as well as the local Alan-Bulgar population.

There is, however, a less well-known but not unfounded opinion that the word “Brodniki” comes from the Brodings (Brodings)—a branch of the Germanic Heruli tribe. This version was once put forward by Russian historian Vasily Vasilyevsky, who doubted the theory that derived the term “Brodniki” from the word “to wander.” In his opinion, it “is not entirely obvious due to the existence of the Germanic people Brodings (a branch of the Heruli), whose name is very close in sound to Brodniki.” The version has a right to exist, especially given the significant role of Germanic tribes, primarily the Goths, in the history of the Northern Black Sea region, Crimea, and the Sea of Azov from the 3rd to the 9th centuries AD.

From the mid-13th century, the term “Brodniki” disappears from written sources, but, as noted above, from the beginning of the 14th century, the term “Cossacks” (“Kozaky”) appears more and more frequently. Most likely, this was due to the intensified Turkification of the vast expanses of the “Wild Field” at that time, whose western part, as the Golden Horde broke up into several warring hordes, came under the control of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Cossack historian and hereditary Don Cossack Yevgraf Savelyev considered the Cossacks indigenous inhabitants of the shores of the Azov and Black Seas, the Don, and the lower Dnieper. Like Lev Gumilev, he believed that “the remnants of the Horde Cossacks who did not join the Kyrgyz (Kazakhs)—their fellow tribesmen who formed a new khanate—could have been the first nucleus around which Russian fugitives gathered.”

Space of Super-Freedom

The Cossacks as we know them, as a socio-ethnic community, are directly connected to the political and socio-economic processes that took place in the territory of modern Ukraine and Russia in the 15th–16th centuries.

First and foremost, this was the intensification of serfdom, both in Muscovy and in the territory of Lithuania, and later the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. But while in Western Europe peasants resisted the increase in feudal dependence by fleeing to cities (the well-known principle “city air makes you free”), peasants from Muscovy and Lithuania fled south, to the Wild Field, where a similar principle applied: “there is no extradition from the Don” (as from the Dnieper).

At this stage, it is almost impossible to distinguish between Ukrainian and Russian Cossacks. As noted above, the city of Cherkassk-on-Don, which for a long time was the capital of the Don Cossacks, was founded by Zaporozhian Cossacks. Moreover, Cossacks, who in Russia were usually called Russian both in literature and in everyday life, generally did not consider themselves as such.

Sopov, in the article “The Problem of the Ethnic Origin of the Cossacks and Its Modern Interpretation,” writes:

“Even in the 1930s, judging by the census, the absolute majority of Kuban Cossacks and most of the Don Cossacks of the lower Don called Ukrainian their native language (and even identified themselves as Ukrainians). The change in linguistic orientation occurred only after the Great Patriotic War.”.

At the same time, Sopov refers to cultural scholar Igor Yakovenko, who draws attention to the fact that “according to some reports, even in the 19th century, Cossacks were mostly bilingual and in everyday life used the ‘Tatar’ (i.e., Polovtsian) language”, as well as the large number of Turkic-origin words among the Cossacks, which are still used today. These include, for example, kosh, kuren, yurt, beshmet, maidan, esaul, ataman, etc.

Almost all Cossacks had in common the type of political organization based on autonomy and military democracy (the Cossack circle—an analogue of the Mongol-Turkic kurultai, as well as the Slavic veche).

However, there is one serious difference between Russian (Don, Terek, Ural) and Ukrainian (Zaporozhian, Cherkasy) Cossacks. This difference is the result of their different historical paths. The Cossacks who lived on the Don, Volga, Ural, and North Caucasus eventually became a special sub-ethnos and/or part of the Russian people. At least, that is the prevailing opinion about them in Russia. But what is absolutely certain is that they became here a separate, specific service class of the Great Russian state. Ukrainian Cossacks were also a special service class in Lithuania and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. But even more importantly, by historical fate, they became the foundation for the formation of the Ukrainian nation and, ultimately, the Ukrainian state.

“The character of the ruling elite of the Dnieper (Zaporozhian) Cossacks was shaped under the influence of the Polish ‘szlachta,’ who did not recognize supreme authority over themselves. This ‘super-freedom’ became a distinguishing feature of the ruling elite of the Dnieper Cossacks. They waged open war against the kings under whose rule they were; if unsuccessful, they switched to the authority of the Moscow prince, whom they also did not wish to obey, betrayed him, and returned again to the Polish king’s authority, and sometimes decided to go under the Turkish sultan.“

Thus, the author of the four-volume work “History of the Cossacks,” Don Army Colonel Andrey Gordeev, wrote about the Ukrainian Cossacks.

The Formation of the Cossacks

The process of the formation of the Cossacks in the form in which they appear to us in later times was also influenced by the geopolitical transformations that took place in Eastern Europe and Asia Minor from about the mid-14th century to the second half of the 15th century.

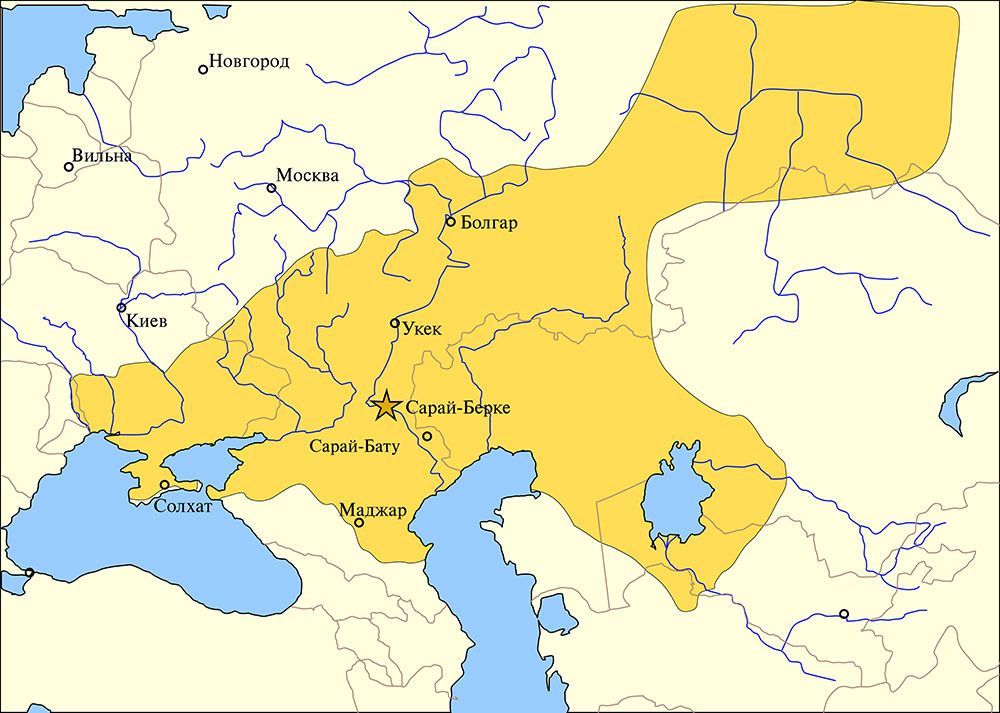

This was a time, on the one hand, of the rise of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and on the other, the collapse of the Golden Horde (Ulus Jochi), the strengthening of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, and the emergence and rise of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1324, the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas defeated the troops of Kiev Prince Stanislav at the Irpin River and, after a month-long siege, captured Kiev. A year earlier, Gediminas had already annexed the lands of the Galicia-Volhynia principality to Lithuania. Almost all the territory of present-day western and central Ukraine came under Lithuanian rule.

In 1362, Grand Duke of Lithuania Algirdas defeated the Golden Horde army at the Blue Waters. Almost all the territory of modern Ukraine, including the then Kiev, Pereyaslav, Chernihiv principalities, Podolia, as well as part of the Wild Field up to the western coast of the Black Sea, became part of Lithuania, which became the largest state in Europe at that time.

This victory of the Lithuanians over the Tatars was of enormous significance for the further historical fate of the Ukrainian people. And not only because Ukraine stopped being a tributary of the Horde several centuries earlier than Muscovy. Another advantage was that the Grand Duchy of Lithuania practically did not interfere in the affairs of the East Slavic lands, which made up most of its territory.

On the contrary, Lithuania adopted the principle “we do not break the old, we do not introduce the new,” which meant non-interference by the central Vilnius authority in the rights of the Orthodox Church and local jurisdictions, which were largely based on the statutes of the Russkaya Pravda —the first code of laws adopted at the beginning of the 11th century in Kievan Rus’.

This favorably distinguished Lithuania, and after its union with Poland in 1569 under the Union of Lublin, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, from the Muscovite state. In the latter, all local features of the political life of the lands included in its composition were immediately and mercilessly eradicated, as happened in 1478 with Novgorod, where veche democracy was uprooted by Ivan III along with the veche bell, which was taken down and transported to Moscow.

But while for Lithuania the second half of the 14th century to the mid-15th century was a period of greatest growth and power, for the Golden Horde (Ulus Jochi) it was a time of collapse. In 1359, the so-called “Great Troubles” began. In 21 years, as a result of endless coups in the struggle for the title of Great Khan, 20 rulers changed. It was during this time that the Golden Horde suffered a series of heavy defeats—in 1362 at Blue Waters by Algirdas, in 1378 at the Vozha River by Dmitry of Moscow, and in 1380 by the same Dmitry at the Don (Battle of Kulikovo). In the last two battles, a key role was played by Volhynian-born voivode Dmitry Bobrok-Volynets.

In 1379, Tokhtamysh became Khan of the Golden Horde. In 1382, he devastated Moscow and restored his influence there. However, after this, Tokhtamysh turned against his former ally and patron, Emir Timur, which proved fatal for him.

Timur dealt Tokhtamysh a crushing defeat in 1395 on the Terek and subjected the main cities of the Golden Horde, including its capital Sarai, to devastating destruction.

Tokhtamysh fled to Lithuania and asked Grand Duke Vytautas for help, promising the ambitious Lithuanian dizzying prospects. In particular, it was about the Golden Horde, in case of victory over Timur, being ready to give up its rights to control over Muscovy and other eastern Russian principalities, which meant that Lithuania could finally unite all the lands of former Kievan Rus’ under its rule. For this, it was only necessary to defeat the young, inexperienced new Khan Timur-Kutlug, who was placed on the throne by beglerbeg Edigu.

Vytautas gathered a powerful coalition of Polish, German, Lithuanian knights, Russian warriors, as well as Tokhtamysh’s Tatars, and declared a “Crusade against the Tatars.” Moreover, his army was also armed with firearms—15 cannons.

In 1399, the armies met in the historic Battle of the Vorskla River. The young Khan Timur-Kutlug was terrified by Vytautas’s numerous army, shining with steel armor. He tried to negotiate with Vytautas. However, the battle-hardened Edigu persuaded him to start the battle. As a result, the Lithuanian coalition suffered a crushing defeat by the troops of Timur-Kutlug and Edigu, and Vytautas’s ambitious plans, and barely escaping after this battle, were dashed.

The defeat at Vorskla pushed Vytautas to rapprochement with Poland.

For the Golden Horde, this victory turned out to be the last in its history. As subsequent events showed, it was already impossible to preserve this state within its former borders. The process of its collapse became irreversible.

By the second half of the 15th century, several independent khanates had formed in its place, including the Crimean, Kazan, Nogai Horde, and several others.

At the same time, the Ottoman Turks, having recovered from the defeat inflicted by Tamerlane in 1402, resumed their expansion in Europe at the beginning of the 15th century. In 1453, the Turks captured Constantinople, thus ending the history of Byzantium. At the same time, the Ottoman Empire continued to expand its influence to the northeast, into the Northern Black Sea region.

The Crimean Khanate became a vassal (according to other sources, an ally) of the Ottoman Empire. For the next centuries, up to the 18th century, the Crimean Khanate claimed succession from the Ulus Jochi (Golden Horde), and, notably, had historical and legal grounds for this: the Crimean Khans—the Girays—traced their lineage directly from Jochi, the eldest son of Genghis Khan. And their “raids” on Moscow in the 15th–17th centuries were explained by periodic delays in the payment of the traditional tribute (“vykhod”), which their vassal, the Grand Prince of Moscow, was supposed to pay them annually. By the way,the legitimacy of paying this tribute was never disputed by the Grand Princes and Tsars of Moscow. The disputes were only about its size and the timing of delays. Legally, this tribute was abolished only by the Russo-Turkish treaty of 1700 under Peter I.

Due to all these events, and primarily because of the collapse of the Golden Horde, vast expanses of the Wild Field (Desht-i-Kipchak)—from the Danube Delta to the Urals—became either “no man’s land,” that is, weakly controlled, or contested by various Turkic (“Tatar”) hordes and khanates, as well as Lithuania and Turkey.

These places became “wild” at the same time—in the 15th–16th centuries. According to the outstanding Ukrainian historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky, at the end of the 15th century, “all Ukraine... became the scene of terrible devastation—Tatar, Turkish, Wallachian… The achievements of civilization and culture of many centuries disappeared in an instant. The entire steppe side, the entire southeastern belt up to the forest line—Pereyaslav, southern Chernihiv, southern and central Kyiv, and eastern Podolia—became a desert...”.

It was to these deserted places that peasants began to flee en masse from the increasing feudal oppression both in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and in Muscovy. Joining them were small-town craftsmen and traders, the so-called “common people,” dissatisfied with rising taxes and the arbitrariness of their rulers.

It was here, in the Wild Field, mixing with the remnants of other tribes and peoples, that the Cossacks known to the whole world today began to form.

At the same time, important trade and diplomatic routes from Moscow, Lithuania, and Poland to Crimea and Turkey and back continued to pass through this territory. These lands, depopulated by that time, were controlled by the Cossacks, who, on the one hand, offered their services as guards and guides to all comers, both for trade and diplomatic caravans, and on the other, did not disdain to rob them.

About the life of the “common people” who became Zaporozhian Cossacks, the 16th-century Polish historian Marcin Bielski wrote: “These common people usually engage in fishing on the Lower Dnieper, where they dry the fish in the sun without salt and feed on it during the summer, and in winter disperse to the nearest towns, such as Kyiv, Cherkasy, and others, having first hidden their boats in some secluded place on a Dnieper island and leaving several hundred men in the kuren, or, as they say, on guard. They also have their own cannons, some taken from Turkish fortresses, some seized from the Tatars.”

At the same time, he notes that “previously (that is, not before the mid-16th century, when his notes were first published) there were not so many Cossacks, but now their number has reached several thousand people“. Thus, it can be assumed that the Cossacks only began to represent a serious force at this time.

At the same time, in the early 16th century, under the rule of Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland Sigismund I, the idea arose in Lithuania to use the Cossacks as an organized military force on the borders with the Crimean Khanate. With the same initiative—to set up a permanent guard of 2,000 men in the lower Dnieper beyond its rapids—in 1533, Cherkasy starosta Yevstafiy Dashkovich came forward. However, this plan was also not implemented.

The first reliably known Zaporizhian Sich (fortified wooden town) was built on the Dnieper island of Mala Khortytsia by Volhynian prince Dmytro Vyshnevetsky (Baida) at his own expense in 1552.

After the creation of the united Polish–Lithuanian state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in 1569, its king Sigismund II Augustus on June 2, 1572, signed a historic universal, according to which Crown Hetman Jerzy Jazłowiecki hired the first 300 Cossacks for service on the southern border. These Cossacks were entered into a special register and received pay for their service.

Thus, in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Zaporozhians were officially recognized and established as a special service class of “registered Cossacks,” that is, people officially in military service to the Polish–Lithuanian state. And a new stage in their difficult history began.

TO BE CONTINUED