Support the author!

«You can’t outplay the secret services on their own turf.» A long conversation about the participants in the famous Sinyavsky and Daniel trial

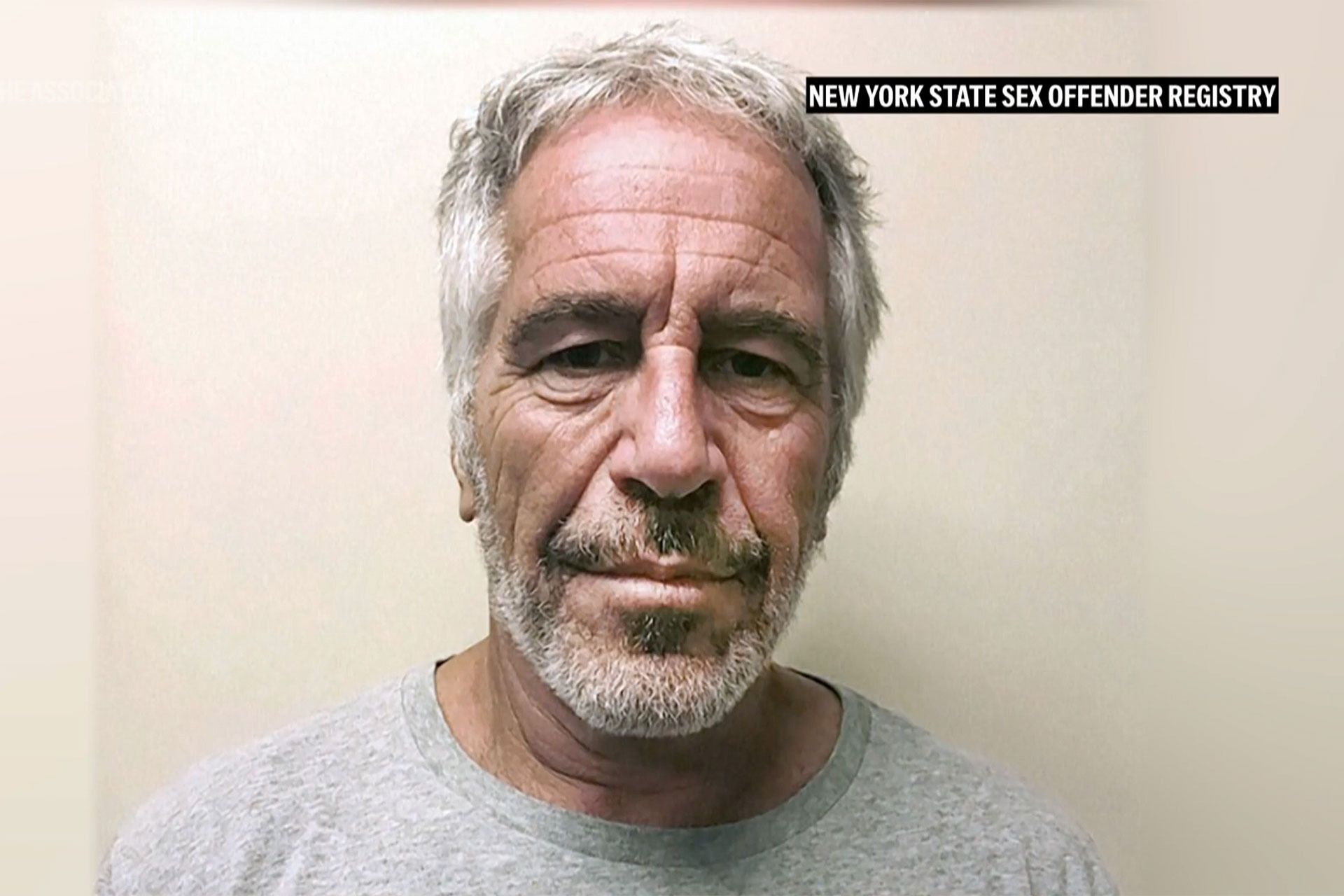

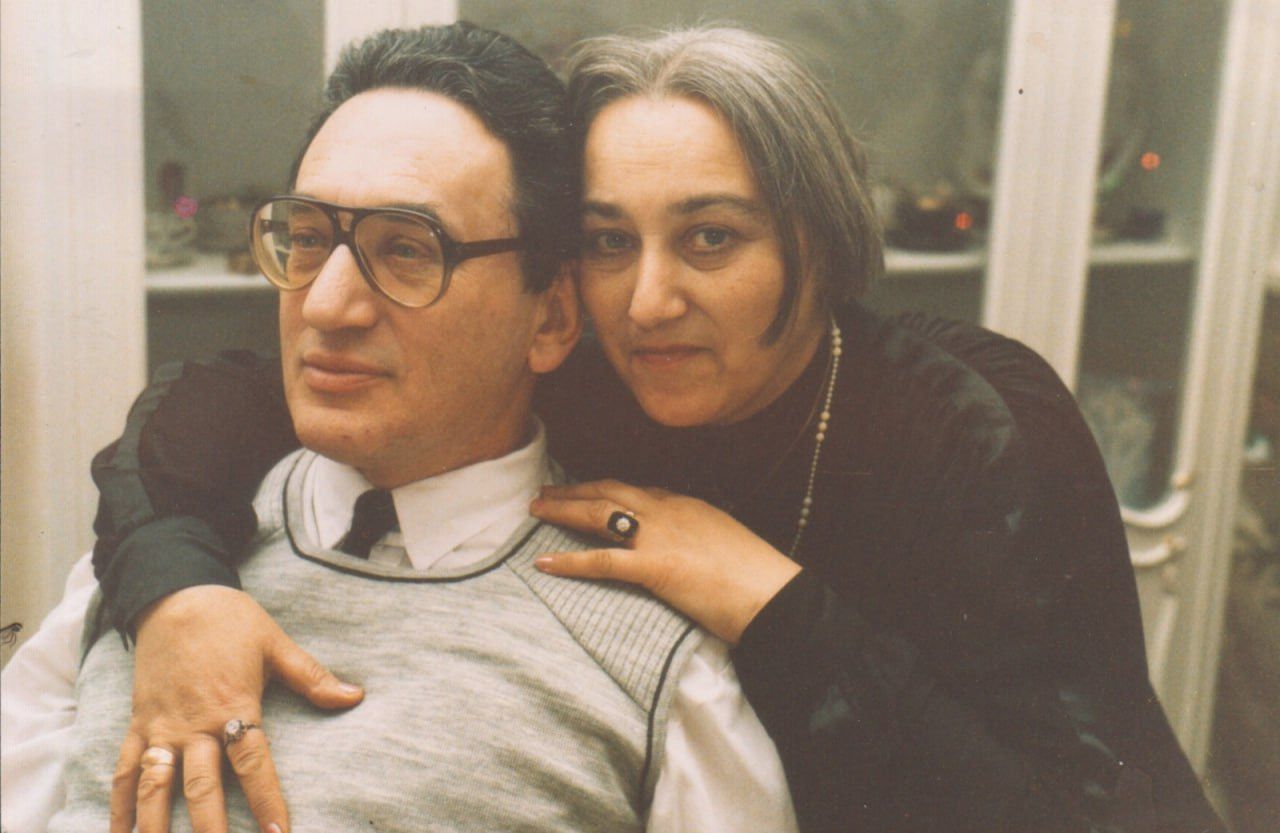

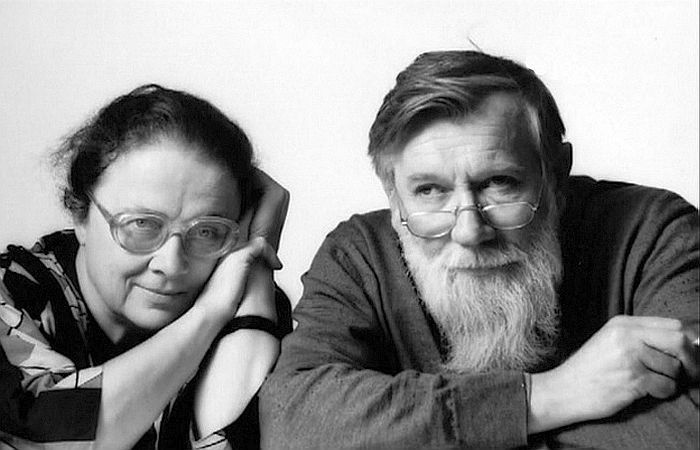

Exactly 60 years ago, the USSR began the trial of writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, which marked the beginning of the Soviet dissident movement. One of the prosecution witnesses at this trial was the Orientalist Sergei Khmelnitsky — the father of historian of Soviet secret services and “Most” columnist Dmitry Khmelnitsky. Dmitry himself was 12 years old at the time. A couple of years later, Dmitry learned that his father had been a secret NKVD informant, whose denunciation in the late 1940s led to the arrest and imprisonment of two of his friends. After being released during the Khrushchev Thaw, they publicly exposed Sergei Khmelnitsky, and all his close friends turned away from him. Among them was Andrei Sinyavsky. However, few people know that the famous writer himself was recruited by the NKVD at the same time as Khmelnitsky and continued to cooperate with the KGB. Dmitry tells how it all happened in his forthcoming book “Khmelnitsky, Sinyavsky, and the KGB.”

- I read the manuscript of your new book with great interest, because I knew almost nothing about the backstory of the trial of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel — especially about the fate of your father, Sergei Khmelnitsky, who was connected to the dissident movement in the USSR and at the same time was recruited by the Soviet secret services. Why did you decide to tell the whole story now?

- My father's story is actually not unknown, but it's often retold in a distorted way. That's why I wanted to get to the bottom of it. He was recruited by the NKVD while still a student, in the late 1940s, to spy on specific foreign students at Moscow State University. In fact, both he and Sinyavsky were recruited at the same time — they were friends, studied together. And most likely, my father was recruited at Sinyavsky's suggestion (I explain how this happened in the book).

But unlike Sinyavsky, my father bore a heavy guilt. He was forced to testify against his friends, Yuri Bregel and Vladimir Kabo — and they each got 10 years. My father's testimony was shown to them during the investigation, so when they were released early about five years later during the Khrushchev Thaw, rumors started spreading. He was talked about as an informant. Bregel and Kabo came to his thesis defense in '64 at the suggestion of mutual friends, who also wanted to get to the bottom of things — and publicly accused him of informing. And after that, we had a kind of “comrades' court” at our home for my father. In general, he was probably one of the very few in the Soviet Union to be publicly shamed as an exposed informant.

- And when and how did you learn about this story?

- About three years later, when I was 14. My acquaintances told me everything, and after that I kept hearing my father's story, always told completely falsely. My father was never a voluntary informant, he was forced into informing. And when the scandal broke out in 1964, there was one relief: the KGB left him alone. As an exposed secret employee, he no longer had any value for them.

But the situation with Sinyavsky continued to develop. Apparently, he and his wife Maria Rozanova really began cooperating with the KGB during his imprisonment. And they emigrated, judging by many signs, precisely as Soviet agents of influence in the West.

- But then why did the Soviet authorities need a high-profile trial of Sinyavsky together with Daniel? And moreover, both of them actually served time in prison.

- They were arrested quite seriously, because from the Soviet authorities' point of view, they really did commit a crime: they published their (not so anti-Soviet, but still disloyal) texts abroad.

And the authorities decided, as I understand it, to use this situation to roll back the Thaw. That's why they were imprisoned in all seriousness, to the full extent. But after that, during their imprisonment, negotiations apparently began, which have been described by many others and which I write about — between Rozanova and the authorities.

Here's a nuance: Rozanova simply could not have avoided being a secret NKVD employee, just by being the wife of an informant. I know this for sure from my mother, who was also forced to sign a nondisclosure agreement. Only my mother never got involved and just cooked at the meetings that took place in our home, while Rozanova [as a secret NKVD employee] was much more active than Sinyavsky in a social sense.

- Tell me, did you discuss this story in your family while your parents were alive?

- No, I never asked my father about it — I knew it was extremely painful for him, and I drew my own conclusions. All his closest friends broke off relations with him back in '64, when everything came out. The comrades' court was held in our apartment, where he was asked for explanations. And his explanations were completely unsatisfactory: he made up some stories about passing information to a certain person who was interested in his friends — and allegedly didn't know that this was an NKVD employee. It was an obvious lie. When in the early '90s I spoke with [Yuli Daniel's ex-wife] Larisa Bogoraz, who was present at the comrades' court, I asked her why everyone broke off with him. The answer was: “But he lied! We all lived in that time, we understood the situation, we asked him to explain how it all was — but he lied.“

For a long time I thought my father lied out of cowardice. But when he died and my mother began writing her memoirs, I asked her to tell me about the hardest thing in her life, especially about cooperation with the KGB. And then something came up that was completely unexpected for me.

My mother talked about what happened on the eve of that comrades' court, at which, by the way, Sinyavsky himself was not present. But the day before the court he was at our house. And my mother remembered how he was walking, backing down the corridor of the communal apartment, and as he said goodbye, he told her and my father: “Guys, whatever you do, don't confess, or everyone will die, both families will die.” I was surprised, and she said: well, of course, it was an article of the law. And then it dawned on me. Secret NKVD employees signed a nondisclosure agreement about everything related to their activities. If they disclosed it, it was considered treason, with all the consequences. That's why, by the way, in Soviet times there were no self-exposures of informants, only after the early '90s — for example, actor Mikhail Kozakov confessed.

I think there were a lot of people who got caught in this trap and were forced to cooperate. As many as the organs needed. Because it was hard to refuse even in the more lenient Khrushchev-Brezhnev times, and in Stalin's time it was a sentence: if you don't want to cooperate, then you're an enemy. If you're an enemy, you go to the camp, that's it. Another matter is how people behaved in this situation.

- How did your father cope with being exposed?

- He moved to Dushanbe, where I actually grew up. He was an Orientalist, so it looked natural. There were no conversations in the family about what had happened in Moscow. When it came to close friends, including Sinyavsky and Daniel, my parents only remembered funny stories. They were all close professionally, too — my father was a poet, a very good one. Not a single bad word was said about them, but my father was very hurt by them. Because Sinyavsky knew exactly why he lied at the comrades' court — and moreover, he himself made up the story for my father to use as an excuse. They had the same NKVD handler.

In 1980 my father emigrated to Germany. Then a situation unfolded. Apparently, Sinyavsky was very afraid that my father, having arrived in the West, would tell everything. Because by then Sinyavsky was an extremely prominent figure in emigration — the most prominent Soviet writer to go West before Solzhenitsyn. And he wrote a book called “Good Night,” in which a whole chapter was devoted to my father. And that chapter was absolutely false, including psychologically. It described a person who had nothing to do with my father — a born informant, malicious, eager to do harm to people. In general, a disgusting figure, the complete opposite of what my father was. I can't even understand how he was an informant, given his naivety and tendency to blurt out anything without thinking — he was absolutely unsuited for the role.

When my father read all this, he was outraged by the unbearable lies. And in 1985 he wrote an essay called “From the Belly of the Whale,” where in great detail, with specifics, he told the story of his guilt and Sinyavsky's role in it — sparing no one, including himself. The essay was published in the magazine “22,” which was published in Israel by my father's friends Sasha and Nelya Voronel — they were at the comrades' court, but in the 1970s restored relations with him on their own initiative. And in the emigration there was a wild scandal: suddenly it turned out that Sinyavsky and Rozanova were informants. And most importantly, by that time there was a lot of evidence that Sinyavsky in emigration behaved like a Soviet agent of influence. He fought with Solzhenitsyn, with Vladimir Maksimov and his magazine “Kontinent.“ There was a completely unbelievable story of Sinyavsky and Rozanova leaving the USSR: they left for Paris in 1973 literally with a train car full of antiques — 18th-century furniture, a valuable collection of old spinning wheels, a collection of icons, which simply could not have been exported from the Soviet Union, and if dissidents were allowed to leave the country at all at that time, all their valuables would be taken from them. In short, a lot of episodes added up to a big picture.

And the Soviet émigré community split into two groups: those who defended Sinyavsky — and those for whom my father's memoirs became a clarifying point in the overall picture.

- What do you remember about the Sinyavsky and Daniel trial, how did these events seem to you in February 1966?

- I was 12 years old, we were already living in Dushanbe. I remember my father going to Moscow — he was called as a prosecution witness, there were no defense witnesses at all. The fact that he was called as a prosecution witness was the subject of all sorts of gossip — that he had also betrayed Sinyavsky and Daniel. That was pure nonsense, moreover, at the trial, according to Larisa Bogoraz herself, he behaved more courageously than anyone else.

Daniel was charged over the story “Moscow Speaks” — its plot was invented by my father and revolved around the Day of Open Killings [according to the story, the CPSU Central Committee in 1960 declares a day in the USSR when anyone can kill anyone — Most.Media]. My father did not know that Daniel had written and published this story abroad, but at the trial he said: yes, that's my idea. He was in general a very outspoken person, and at a party in Moscow, when someone came and said they'd heard such a story on “Radio Liberty” or “Voice of America,” my father exclaimed: “What! That's my idea, that's Yulka!” Everyone gasped, Daniel, of course, was told about it, and when my father was asked about it at the trial, he said: “Yes, we talked, Daniel scolded me for it and he was right.” Why was he right, they asked — and he replied: well, you can't publicly mention someone as the author of an anti-Soviet publication, that's mean.

That's what my father said at the trial, and it's recorded in the “White Book,” published by Alexander Ginzburg — with transcripts of the trial of Daniel and Sinyavsky: the transcripts were made by Larisa Bogoraz, transcribed by Nelya Voronel, and Ginzburg served time for this book.

- Sinyavsky and his co-defendant's lives turned out very differently. Yuli Daniel never emigrated, stayed in the Soviet Union, after his release lived in Kaluga, earned a living through translations under a pseudonym, and died in Moscow already during Perestroika. Do you know how he lived after his release?

- I know his story mainly from various memoirs. But, generally speaking, their fates began to diverge even in prison. Sinyavsky served time relatively comfortably: he wrote long letters home, from which, I think, “Strolls with Pushkin” and some other texts later emerged. And he behaved extremely quietly.

Daniel, on the contrary, participated in protests, demonstrations, spent a lot of time in solitary confinement, supported other prisoners. In general, he served hard time. And he served the full sentence. He got five years — and served all five, with the last eight months in Vladimir Prison.

With Sinyavsky the situation was different. They wanted to release him earlier, and as far as I understand, there were talks with Rozanova about persuading him to accept a pardon. But he said only together with Daniel — because otherwise it would look bad: he gets released, but Daniel doesn't. That was one of the reasons why Daniel was released first, and only later Sinyavsky was pardoned early. And a couple of years later Sinyavsky left for abroad with that same train car of antiques.

As for Daniel, things are less clear. Sergei Grigoryants, for example, believed that Daniel to some extent knew about Sinyavsky's activities and that was why, so as not to endanger his partner, he kept silent for life. He never took part in anything else. In fact, strictly speaking, neither of them participated in any dissident movement in the Soviet Union after the trial. But Sinyavsky left, and his activities abroad were, to put it mildly, dubious. And Daniel just lived, did translations. And, most regrettably, left no memoirs. Although, perhaps, someone did record something from him.

- And Larisa Bogoraz?

- She was the one who really engaged in dissident activity. In fact, her family with Yuli Daniel fell apart even before the trial. In August 1968, she was one of the seven brave people who went out on Red Square to protest against the occupation of Czechoslovakia. She ended up in exile. She married Anatoly Marchenko, a famous dissident who died in prison in 1984 after a hunger strike.

- How did your father end up in the West, and what did he do there?

- My father emigrated in 1980 on an Israeli visa with my mother and brother, and ended up in West Berlin (I already had my own family by then, so I left much later). He was, as I already said, a truly remarkable poet. The only collection of his poems was published in Riga in the 1990s. And he continued to work in his field — he was a historian of Muslim architecture, wrote a whole series of fundamental studies on the history of medieval Muslim architecture, which are now highly valued.

- Your manuscript ends with two epitaphs for Andrei Sinyavsky written by your father; I think he wrote them while Sinyavsky was still alive?

- One epitaph, of course, is not real — it's a humorous poem, from the 1950s. The real one was written when Sinyavsky died, I found it among my father's papers. It's a good quatrain, I think. But the humorous one is also good.

***

To A. Sinyavsky

That's how it goes in Russia. That's how it happens, — believe it or not,

We have no right to change anything in the laws of nature:

No real poet dies a natural death, —

Either he himself, or someone else takes him out.

Only Fet escaped this bitter fate of ours.

The question arises: was lucky Fet really a poet?

You are a poet, my Andrei, and this cup will not pass you by,

Because, in my opinion, you are a real poet.

It's good before bed to quietly lock yourself in the bathroom,

Stick the barrel behind your teeth, read — “turn off the light when you leave,”

Shout: greetings to all! — and fall head over heels into the black,

The closet that awaits everyone sooner or later in this world.

Evening will be just like any other, in green-orange paint,

But the door will fly open, buzzing like a fire alarm,

The building manager will shout: Professor Sinyavsky hanged himself! —

And will rush off, leaning, to dial the payphone.

***

In memory of Andrei Sinyavsky.

Forget the grudges, leave the quarrels behind.

He lived as he died, keeping the secret.

He vanished like steam. But to be honest —

I never really understood why he needed me.

17.2.1997

- Did Sinyavsky and Rozanova's heirs make any attempts to reconsider their legacy and their role in the dissident movement?

- They have a son — the French writer Egor Gran, who is not much younger than me. One of his novels touches on the family history, and there's a character who is an informant — a recognizable image of my father. It looks like a literary reflection of Rozanova's stories. About twenty years ago there were rumors that Rozanova was writing memoirs and Dmitry Bykov was helping her — they were friends. Then, in 2011, my mother's memoirs “That's How Our Life Turned Out” were published in St. Petersburg, and after that, nothing more was heard about Rozanova's memoirs.

- What does this story mean to you today? Do you want to put a final point on it with your book — to speak for your father, who can no longer defend himself?

- Yes, of course. I'm just tired of explaining to acquaintances over and over how it really was. Because all sorts of things were pinned on my father, including informing on Daniel and Sinyavsky. Besides, I have a completely academic interest in this story: after all, I'm a historian of the Soviet era. And the Sinyavsky and Daniel trial is a crucial turning point where much ended and much began.

It was important for me to figure out this story as an outside researcher — to compare everything and understand who is who. Because with my father it's pretty clear. He was subordinate, got caught in a trap, and bears guilt. He knew it, he had nothing to hide — and after 1965 his whole biography is absolutely transparent.

But the story of Sinyavsky and Rozanova, which lasted until Rozanova's death in 2023, is dark, unrevealed, but extremely important for Soviet and post-Soviet history. There's too much that's unclear there.

I think that if the archives are ever opened, a lot more interesting things will come to light. One of the most telling episodes is connected with Bukovsky's documents. In 1991, Yeltsin invited Vladimir Bukovsky to prepare for the never-held trial of the Communist Party, and he was allowed to work with unclassified Politburo documents — without inventories, at random.

Among other things, there were documents related to Sinyavsky's story: a couple of Andropov's reports to the Politburo asking for his pardon and permission to leave the country. From them it followed that there was an agreement between the KGB and Rozanova: she abides by the conditions, exerts “positive influence” on others, including Ginzburg and Daniel, and in this connection requests permission to leave.

Of course, these documents don't directly mention recruitment — and it would be strange to expect that. But from the context, it's clear what's going on.

When one of these documents was published by Eduard Kuznetsov in the Israeli newspaper “Vesti,” a scandal broke out. Rozanova tried to deny everything and accused Bukovsky of falsification on the grounds that the publication was incomplete. But the omitted parts didn't change anything fundamental. Later, Bukovsky posted all the documents online, and they are still available to everyone.

I still don't fully understand what Sinyavsky was like. He was an extremely secretive person, loved to pretend, to create different images of himself. And Rozanova, in my observation, was bold, cynical, and brazen, yet managed to act in such a way that no one even took offense at her. I think she wasn't very smart, because she let too much slip. She herself used to say that you have to know how to negotiate with the KGB, not realizing how that sounds to people who know what it means.

For example, in interviews over the years, she explained Sinyavsky's release by claiming she threatened the KGB with a certain book written in the camp. But this version is absurd: if a prisoner is found to have an anti-Soviet book in the West, he isn't released — his sentence is extended. Nevertheless, journalists who spoke to Rozanova usually didn't ask her extra questions — even though the lie is obvious.

- A bit of a didactic question as we wrap up. Something like: what does this story teach us? Can it somehow be projected onto today? In general, I want to build a bridge from 1966 to 2026.

- The secret services haven't fundamentally changed since then, of course. They've become much more active and have a much broader reach. Though the quality of their staff is lower. Back then they were much more cultured. And this story teaches us that you shouldn't get involved with the secret services in any way. You can't beat them at their own game.