Support the author!

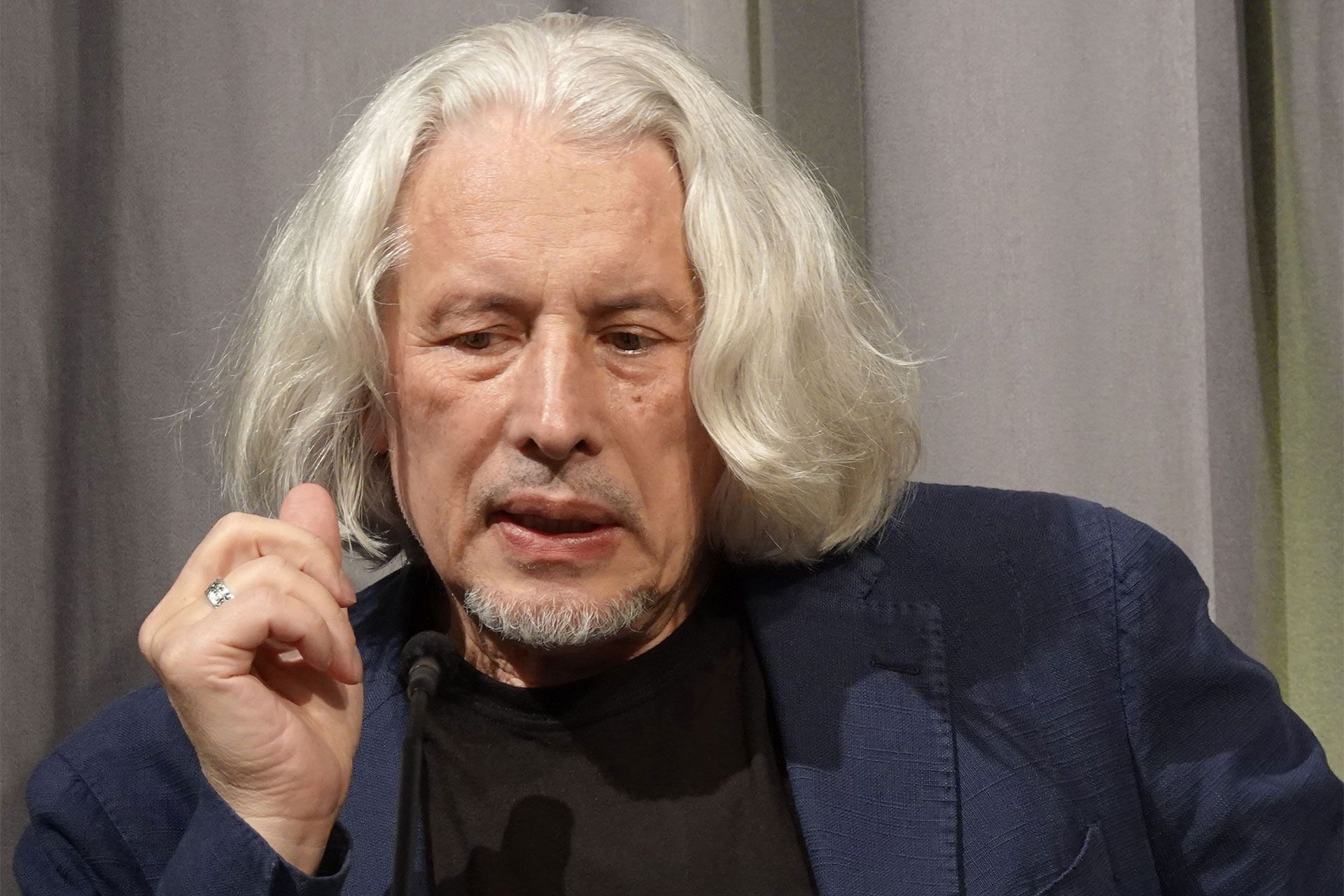

The Writer of the Russian Snake. On the Seventieth Anniversary of Vladimir Sorokin

We have long been inside his endless Telluria, living within his self-fulfilling prophecy, tumbling inside the Machine of Violence he described. And it cannot be said that we were not warned; Russian literature has never before had such a clear prediction over the past decades leading up to the catastrophe.

Publication prepared by the media project “Country and World — Sakharov Review” (project Telegram channel — “Country and World”).

When we say that something happens “in a Chekhovian, Tolstoyan, Dostoevskian” way, it means viewing the world through unique lenses that allow grasping the world as a whole—but each time differently. To see the world “in a Sorokin way” means “laughter through the unconscious,” a bitter smirk of a person who understands the full tragedy of their existential situation.

Sorokin’s writing, among other things, is very democratic; it lets in anyone—who wants to enter, of course. The “filth” waiting for us at the entrance (in the words of Sorokin’s detractors) is simply a radical demand from the 21st-century individual, a critical readiness to expose oneself naked, without crutches, facing existence. To be alone with the frightening essence of what is happening, to “speak the truth”—to oneself, above all (a refrain from Sorokin’s “Ice Trilogy”).

Observing external decency, loyalty to traditions, and the absolutization of culture as such have by no means been obstacles on the path of fascism, wrote Hannah Arendt. Nor were they obstacles for other totalitarianisms, we would add. Any cultural taboo rather helps totalitarianism than hinders it, as it establishes a dam, a barrier to thinking, preventing thought beyond what is allowed.

However, the absence of taboos is also not a universal magic wand.

Postmodernism was understood in Russia in the 1990s-2000s partly as “everything is permitted.” And this carefree animality through cynical laughter is a vivid sign of new evil.

The only consolation is that evil now no longer builds illusions even about itself. This nakedness, the frankness of evil, “without theories”—let’s hope, will help in historical perspective to recognize its essence much faster than before.

In the USSR, it was customary to award veteran writers the title of Hero of Socialist Labor on their 70th birthday (in the slang of those years, “Gertruda”). Applied to Sorokin, this sounds like a deliberate joke. But his creative method allows us to imagine such a utopia. Suppose the “beautiful Russia of the future” wants to thank Sorokin for the meanings he has given and invites him to the Kremlin palace to pin a gold star on his jacket. First, this is still impossible to imagine even under the best circumstances: primarily because no idea of power, even a “good” one, is compatible with Sorokin. Secondly, people raised on Sorokin's books (if they understood him correctly) would most likely turn the Kremlin into a “sugar-coated”—some kind of amusement attraction, not a symbol of power.

Sorokin deserves another award, symbolic: so that people become more attentive to evil. A signal of ideological falsity is usually aesthetic falseness: early Sorokin, who slammed socialist realism’s belly, with its cardboard heroes and speeches—it's all about that. At the same time—a paradox: Sorokin is very classically Russian. He thinks in large chunks, big concepts—and in the magnitude of his talent, he is an heir to the Tolstoyan tradition in Russian literature. One of the best descriptions of Sorokin I have heard is: “the disobedient son of Tolstoy.” Amusingly, even Tolstoy himself (unlike, for example, Dostoevsky!) cannot be imagined coming to the ruler for an award at the palace.

It cannot be said that Russian literature had not previously worked with violence, nor warned of the problem. But Sorokin did this most consistently, from the beginning of his work in the late 1970s–early 1980s. Socialist realism liked to repeat words about humanity, “to remain human!” (of course, in relation to their own, not the enemies of Soviet power). In this sense, Sorokin fully corresponds to the previous canon: Violence is, first and foremost, human.

Both pre-revolutionary and Soviet culture (official and dissident) were confident that we are generally “good,” only the system is bad. It is enough to fix the system—by enlightening more, or feeding better, if not with food, then with ideas—and the person will become better. After Sorokin, Russian culture is forced to admit that the “badness” of a person is something essential, originally inherent to them.

Dmitry Bykov (also a Sorokin admirer) has a poem from the 1990s about how not so much the practical manifestations of violence are frightening, but the awareness that it is “possible.”

Sorokin showed that a person himself, Soviet or post-Soviet, is capable of everything, the very worst. And today this assumption is confirmed by millions of examples—with Sorokin’s immediacy; mass murder has become a profitable, lucrative job, and millions are engaged in this “work.”

Another theme, a recurring motif in Sorokin’s recent decades, is the demise of Russian culture in the 21st century, the gradual disappearance of this currency from world circulation. The most terrifying image in Sorokin is in “Heritage” (2023)—how steam locomotives are drowned in human bodies in some post-Russia. This is a symbol of dehumanization, of course. But this image also has another interpretation: for the last 20-30 years, Russian culture has been drowning its locomotive with the themes and ideas of dead classics, the spirit and hopes of the past. At first, this gave some heat, but now the stock has run out. And no new stock has been created.

In the 1990s, there was hope—for a general improvement of morals. Something inevitably good should happen on its own—after all, so much suffering had happened in the past, and besides—“it’s so natural!” (in this belief, there were probably echoes of the former Marxist conviction in the “inevitability of history, driving forces,” etc.) Of course, the Soviet will not disappear immediately—it awaits a certain period of decay. The symbol of this decay was Sorokin’s famous novella from “Norm” (1979), popularly called “Martin Alekseevich.” The obsessive speech of the main character, the flickering of his consciousness between banality and madness—many thought this was the process of the Soviet disintegration, into molecules, into atoms of speech. Before finally disappearing into oblivion, the Soviet must speak out to the letter, to the interjection, vomit everything out to the last point. And the new propaganda was seen as such a “Martin Alekseevich,” the last phase of verbal incontinence. “But someday they will finally speak out!”—that was the thought.

This was another common misconception—and perhaps Sorokin himself also believed—that totalitarian consciousness would disappear on its own. It does not disappear by itself—that is the most tragic discovery of the 21st century. For it to disappear, some effort is required from everyone (though it is unclear what exactly: appeals to reason and rationality, as we see, are not the key to totalitarian consciousness). Totalitarianism has proven capable of infinite self-reproduction—each time taking increasingly frightening forms. The new reincarnation of “Martin” is philosopher Dugin, who proposes that everyone burn together in the fire of history on a nuclear spit, and thus finally “cleanse” themselves.

What, however, words can be found today to till this Russian experimental field without burning it to the ground? The paradox of the post-catastrophic time: many words from the old lexicon now seem endlessly false. Today, one can only read what does not promise a quick exit from the nightmare: Kafka, Beckett, Kharms—and Sorokin.

It is so unexpected that today Sorokin tries to find words of consolation—often turning to fairy-tale, folk-style plots. Fairy-tale time is infinite, unregulated—in this sense, it has resilience. Another important point: the fairy tale is a mechanism of multiple initiations, the hero’s ability to renew himself. True, for this, the fairy-tale hero must go through a series of trials. Whether he will manage to pass them—and we with him—is God’s will; but such a view of the nightmarish reality at least provides psychological support—and leaves an option for hope.