Support the author!

«The Hardest Winter in Four Years of War»

Old New Year has passed, the Christmas holidays are over, and 2026 has fully come into its own. The wild start to the new calendar stretch—Nicolás Maduro’s nighttime flight, the resurgence of piracy in the Atlantic Ocean, and blood-soaked Iran—may have pushed into the background the fact that we have now been living for four years in the largest war in Europe in the last 80 years.

Over time, it has been hard not to start seeing this conflict as something eternal, transcendent, and doomed to constant self-reproduction. But any war, in principle, is not splitting a uranium atom or an Antarctic anticyclone. It is not driven by impersonal forces of nature, but by the will (or sometimes the lack thereof) of specific people. Let’s look at five factors that can either bring closer or delay the end of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

-

Are the Russian Armed Forces capable of causing an energy collapse in Ukraine?

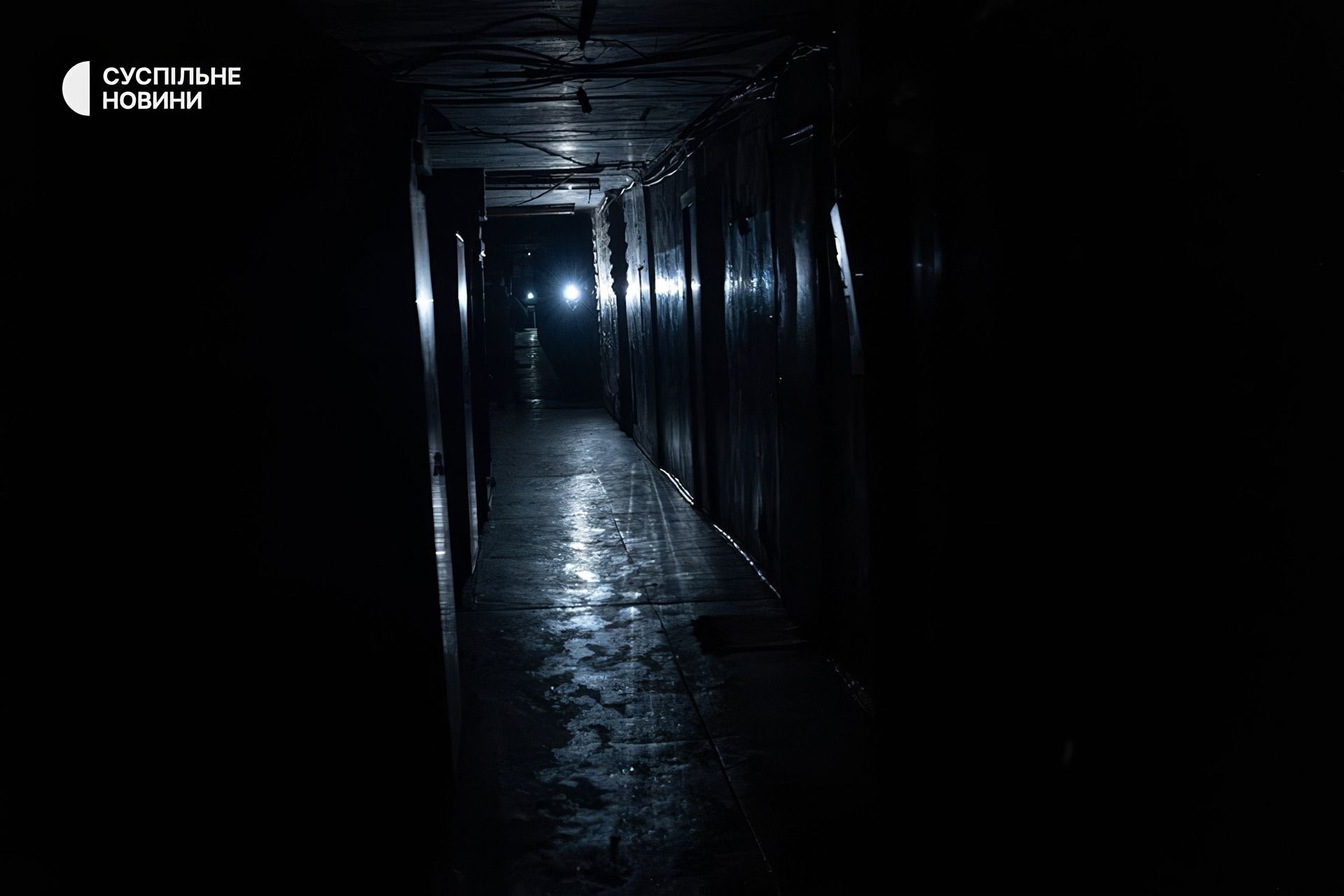

Promises to freeze Ukraine or all of Europe have long become routine for the Kremlin leadership and its media machine. However, in the first days of 2026, Russian troops finally fulfilled an old threat. Ukraine—and above all, Kyiv and its surroundings—was hit by an unprecedented blackout after a series of Russian air strikes on the country’s energy system.

Ukrainian media are extremely candid. “The hardest winter in four years of war”—without mincing words, right in the headline writes TSN.ua. Other Ukrainian news agencies are in agreement. The number of disconnected apartment buildings is in the hundreds, and the duration of the blackouts in some places is measured in days. There are still many questions about the situation, and the authorities avoid giving even approximate timelines for when things might return to relative normal. Nevertheless, Ukrainian society in this extremely difficult situation has once again shown more solidarity and empathy than panic and division.

I can’t help but note how Ukrainians are coping with problems […] Entire entrances of apartment buildings pool money for large generators, on [social media] there are ads for diesel delivery, warm socks, installation of wood stoves, and clearing snow from solar panels. Those who have heating invite those without it to stay with them. Rural residents host city dwellers. In short, no one is giving up or surrendering.

But in wartime, the mere acknowledgment of a problem by Ukrainian media predictably delighted their pro-war colleagues in Russia. For the censored Russian internet these days—it’s a holiday, z-editors relish the suffering of Ukrainian residents. At the same time, they carefully ignore the fact that a similar blackout is happening in Belgorod, where the energy infrastructure was bombed in retaliation by the Ukrainian Armed Forces. It must be said that this retribution was rather pointless. The rest of Russia has long considered the frontline region a special zone, and the misfortunes of its residents don’t particularly affect the general public. Symptomatically, the governor of the Yaroslavl region, Mikhail Evraev, recently called Belgorod one of the “new regions”.

Even less do external forces care about unfortunate Belgorod, especially when it comes to such a specific observer as Donald Trump. In the January “energy war,” the American president clearly saw evidence of Russia’s inexhaustible power and Ukraine’s ultimate doom. That’s why he returned to his favorite rhetoric: Putin wants a “deal,” Zelensky isn’t ready for it yet. Therefore, by Trump’s logic, it’s the Ukrainian, not the Russian president, who is to blame for the war’s continuation.

So strikes on rear infrastructure are a factor that generally works in favor of Russian leadership. Even though the enemy manages to restore its energy system every time. Ukrainians, despite all their desire and ingenuity (as in the memorable “Spiderweb” operation), cannot respond on a comparable scale, and foreign partners, when seeing burning power plants and powerless homes, see more vulnerability in Kyiv than a reason to help an ally. Meanwhile, air terror provides the pro-war audience in Russia with the content it craves, especially as they are troubled by the lack of convincing victories on the ground.

-

Will the Ukrainian front collapse under Russian pressure?

That 2025 was generally unsuccessful for the Russian Armed Forces in terms of those infamous maps with arrows can be seen from one not-so-obvious fact. In the summer and autumn, the once-favorite phrase sanitary / buffer zone disappeared from Russian officials’ vocabulary, as did hints that “new regions” could become more than four. In other words, the military-political leadership silently admitted that it was unable to occupy any significant part of the border Sumy and Kharkiv regions. At least for now.

Things went little better with another cherished z-dream—the complete capture of Donbas. By summer, riding a wave of optimism after the relatively easy liberation of the Sudzhansky district from the Ukrainian Armed Forces, Russian propaganda constructed, without irony, a rather successful concept. Supposedly, the past errors, technical shortcomings, and misunderstandings of the enemy were fixed, plus they had numerical superiority. Not with a single powerful blow, but with the “thousand cuts” tactic they would bleed the enemy dry, and its defense would collapse.

Did it work in 2025? No. In the end, the Russian Armed Forces captured only two towns last year—Chasiv Yar and Sievierodonetsk (the Ukrainian-abandoned Toretsk at the start of 2025 is better left aside here). Both towns, with a combined prewar population of less than 25,000, are in the Bakhmut district. Yes, the same district whose center was taken three years ago (!) by the now-deceased Prigozhin when Shoigu was still defense minister.

In peacetime, any driver could get from Bakhmut to Sievierodonetsk or Chasiv Yar in less than an hour. For the Russian army, that journey took not months, but years.

In the northwest of Donetsk region, in the Pokrovsk-Myrnohrad agglomeration, the attackers got bogged down in protracted fighting. Ukrainian forces still control separate neighborhoods there. As for the city of Kupiansk, which Vladimir Putin had grown fond of (administratively not Donbas, but Kharkiv region), the Russian army lost it—at least its central part. And this happened right at New Year, just after the Russian Army’s top commander’s “Direct Line” program, where he assured that Kupiansk was securely “liberated.”

There’s no point listing the year’s results at every section of the front. One number says it all: 0.72. That’s the percentage of Ukrainian territory occupied by Russian troops in 2025. According to OSINT analysts, the attackers paid for this meager gain with the lives and health of over 400,000 of their soldiers for the second year in a row. So it’s unclear whether the Russian Armed Forces have enough reinforcements for new minor successes this year.

For now, it looks like if the Russian army inflicted a “thousand cuts,” it did so on itself. And the Ukrainian forces—despite undeniable manpower shortages and interruptions in Western aid—still hold the front with minimal territorial concessions. But any war is nonlinear, so there’s no guarantee that everything we’ve seen over the past three years will inevitably repeat in the fourth. At least in the Russian-Ukrainian struggle, an unexpected front has already opened. Specific actions are taking place around oil tankers.

-

Will Ukraine paralyze the “shadow fleet” of Russian tankers?

Ukrainian strikes on Russian oil facilities aren’t new. Since late 2024, Ukrainian drone operators have regularly hit refineries, port terminals, and pumping stations. Other infrastructure objects have also been targeted. In 2025, an average of 11 drones hit Russia daily.

But late last autumn, Ukrainians opened a new front—strikes on oil tankers suspected of belonging to the “shadow fleet.” These are the vessels that allowed Russia to trade raw materials via elaborate schemes, bypassing international sanctions. Typically, these tankers are not new, have international crews, and sail under the flags of exotic countries like Gabon or Palau. Ukrainians began hunting them worldwide, from the Black Sea to West Africa.

In November-December 2025, RBC agency counted five such attacks, and in 2026—two more. Official Kyiv, represented by the Security Service of Ukraine, did not hide responsibility, and explicitly emphasized the need to fight Russia’s “shadow fleet” by any means. Apparently, the “ocean theater” of war became possible with at least the silent consent of the US presidential administration. Driving down global oil prices—and thus undermining Russia’s four-year-old “gray” infrastructure—is in Donald Trump’s interest. A rare moment when Kyiv and Washington’s goals surprisingly coincide.

US sanctions have already slashed Russian seaborne oil exports by about 20%. This happened after, at the end of October, Donald Trump’s administration blacklisted Russia’s two largest oil producers—Rosneft and Lukoil. [...] If in October, about 3.6 million barrels of oil were shipped daily from Russian ports, then in the first week after the sanctions, according to Bloomberg, these volumes fell to about 3 million barrels per day.

- Denis Morokhin, Novaya Gazeta

However, not all outside players are thrilled with Ukrainian special operations. The SBU drones hit the wallets not only of Russia, but also of other countries far from supporting the Kremlin in the war. Last year, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan already called strikes on civilian vessels in the Black Sea unacceptable, and a couple of days ago Kazakh diplomats expressed solidarity. Astana’s outrage is understandable: drones struck the tanker Matilda, chartered by a subsidiary of the national company KazMunayGas and supposedly unrelated to Russia.

It’s still unclear what Ukraine will achieve first—cutting the volume of “gray fleet” deals or spoiling relations with neutral or even friendly countries. Ultimately, Russia’s oil revenues are determined less by rusty tankers under exotic flags than by the price of their cargo.

-

Will falling oil prices leave Russia without money for war?

The good news for Ukraine is that its opponent is not doing well with prices for its key commodity. Back in April-May, Moscow’s monthly oil export income fell from a trillion rubles to about half. Eight months have passed since, but the figure hasn’t returned to its previous level.

The situation looks doubly alarming for the Kremlin when comparing the results of 2025 and 2024. Total income for 2025, according to Reuters, will be less than 8.5 trillion rubles—a quarter less than last year. Worse, this is well below all, even the most conservative, Finance Ministry forecasts. In other words, the financial-economic bloc remained cautiously optimistic until the end, but budget revenues will fall short of even the most cautious expectations.

The reasons for the decline are obvious: a relatively strong ruble, sanctions pressure, and reduced international business activity. Russian authorities, of course, can crash their own currency (at the cost of price spikes and public discontent), but they have less and less room to bypass Western restrictions, especially with Trump’s piracy in the Atlantic. And the Kremlin, no matter how much it wishes, cannot increase the volume of global trade. So the likely reality for 2026 is Urals oil prices in the range of $40-45, a third lower than a year ago.

Russian exports will be under double pressure—sanctions on the one hand, and a glut of bearish sentiment on the oil market on the other. And the search for alternative buyers will mean increasing discounts on toxic Russian supplies.

A prolonged drop in Russia’s oil revenues—its main source of hard currency—is inevitable. Does this mean that war costs will become unjustifiably high, and the Kremlin will rush to make peace before it’s too late? Not at all. First, the Russian authorities have clearly saved more in the past three fat years than they have spent. Reserves still remain. Second, Putin still has a “new oil” in the form of citizens forced to pay taxes, duties, excises, and fines.

According to the most cautious forecasts by European economists, Russian authorities can afford to finance the war at least until the end of 2026. There is little doubt that they are ready to stop the bloodshed only on terms other than Ukraine’s capitulation. And here we return to the original thesis: wars are not natural disasters, they are started, waged, and ended by living, ordinary people.

-

Will a “black swan” inside Russia stop the war?

Almost all of 2025, Russian society spent naively waiting for some magical intervention by Donald Trump. The spontaneous popular belief of millions was that a wizard in a presidential jet would come and end the war for free. This narrative was believed so fervently that the most cunning recruiters for the “special military operation” used it in their ads—hurry and sign a contract and get money before the good American conjures up peace.

By the end of the year, it became clear: this faith was based on nothing. Trump had neither effective levers to influence both warring sides, nor the desire to understand the nature of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Yes, according to some statements by the US president, he is sometimes repulsed by the Kremlin’s blatant lies and senseless cruelty. But then Trump always returns to his familiar worldview: Russia is a great power, and Ukraine is no more than its lost province. Of course, Russians have no business in the Western Hemisphere, but in their own neighborhood they are entitled to a sphere of influence. So, by and large, Moscow is right in the war, and Kyiv should listen to its bigger neighbor—especially since it can’t regain lost territories on its own.

After the diplomatic farce in Anchorage, the deep faith in Trump the peacemaker dried up. Is anything left? Sociologically, Russian society after February 24 is a black box. No one can say for sure how Russian citizens now perceive the war and what ideal outcome they see for it, especially given differences in education, income, or region. Theories of Russians universally thirsting for Ukraine’s destruction are as speculative as the theory of it being “Putin’s war alone,” which ordinary people endure out of fear.

One thing is certain: after February 24, Russian society was pumped for too long with an extremely toxic cocktail. A cocktail of legal nihilism, a cult of strength, hardcore conspiracy theories, and the most rampant xenophobia. We can only guess how this mix will explode if frontline failures, a sharp drop in living standards, and a public display of weakness by the current leadership coincide. It’s especially interesting how the army will behave, whose combat effectiveness has recently been maintained by “cripple battalions”, “nullifications” and cages for people—practices that contradict the letter and spirit of any army’s code of conduct and would probably horrify even Mexican drug cartels.

History shows that when a society is infused with such blatant evil for so long, it does not go without consequences. The only question is whether traumatized people will take it out on their equals (this has already begun; Interior Ministry statistics show a record number of serious and especially serious crimes in 15 years) or remember those who deliberately and methodically taught them to be cruel?