Support the author!

Russian prince who refused Kiev: the life and adventures of Alexander Nevsky

The familiar image of the prince is almost entirely woven from myths. Why “with the East, against the West” is not about him at all?

In the pantheon of historical figures significant for the leadership of the Russian Federation, Alexander Yaroslavich (Nevsky) holds a special place. A man who died over 760 years ago posthumously serves several functions at once. He is both the “Complete Works of Lenin 2.0,” to whom one should refer when making political decisions, and a “wise predecessor,” whose legacy can be showcased under any circumstances, and an object of worship—in the literal sense, since the pious Prince Alexander was canonized by the Russian Church almost 600 years ago. Just a week ago, blessed the Northern Fleet submariners with his icon.

Moreover, this image is purely “sovereign” and anti-Western. It is assumed that it was Prince Alexander who made a kind of “civilizational choice” after which Russia became completely alien and unpleasant to the West. Incidentally, this thesis is also the basis for criticism of the medieval ruler in (quasi)historical circles. The claim is that all the Asian influence and despotism in the Russian tradition come from this politician rejecting the outstretched hand of Catholic Europe and preferring to serve the Horde instead.

Without touching on the absurdity of the question itself (is it appropriate to blame a 13th-century person for 21st-century events?), let's try to understand: did Alexander Nevsky really “not accept help from Western partners”, make the notorious anti-European “choice,” and voluntarily become a vassal to the Horde?

Man of a fragmented era

Prince Alexander Yaroslavich was born around May 13, 1221. It should be noted: the exact day of birth of the ruler, like most of his contemporaries, is unknown due to the passage of time. May 13 is a conventional date chosen according to the feast day of the heavenly patron of the future commander, the 4th-century martyr Alexander of Rome. The bitter irony is that the Roman Alexander once paid for refusing to worship pagan gods, whereas the Russian Alexander largely achieved success precisely due to his receptiveness to pagan rituals.

However, let's not get ahead of ourselves. Alexander’s birthplace is known precisely—Pereslavl-Zalessky. Today it is a modest town halfway between Moscow and Yaroslavl, but in the early 13th century, it was one of the largest centers of all Northeastern Rus. In fact, Alexander's father, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, one of the powerful rulers of his time, ruled in Pereslavl. The first quarter of the 13th century should be recognized as a rather strange period in the still unified history of the lands of Kievan Rus. These years are now simply characterized as a time of feudal fragmentation. However, officially, a united state with a common Old Russian language and Orthodox Church still existed at that time.

It was believed that Rus was held together by the ladder law—a hereditary principle of succession where the nominal supreme power (in Kiev) passed not from father to son but by simple seniority among the Rurikids. In theory, this supposedly restrained the younger princes from open separatism—as they changed “thrones,” they rose from less prestigious places of rule to more honorable ones. But in reality, Rus split into 12-15 separate principalities ruled by rival branches of the ruling family. For example, in 1216, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich waged war against his father-in-law Mstislav the Fortunate and lost. After the victory, Mstislav even reportedly took back the daughter Feodosia, whom he had given to his son-in-law in marriage.

Later, apparently, the young men reconciled, and Feodosia bore Yaroslav nine children. By seniority, Alexander was originally second but became the de facto eldest after the early death of his older brother.

Little is known about Alexander's early years, and no authentic contemporary portraits have survived. It is only known that his mother was half Polovtsian, so the appearance of Feodosia's son might have differed from the stereotypical Russian image of a fair-haired man with a thick curly beard.

Most of Alexander’s childhood was spent not in his native Pereslavl but in Novgorod, where his father ruled four times between 1215 and 1236. For its time, this city was a true metropolis, enriched by northern expeditions and trade with Western Europe. In the fifty-thousand-strong Novgorod, there was strong self-government; all important matters were decided by the veche—a gathering of full-right adult men. Since 1136, Novgorodians had the right to independently invite a prince: as a military commander and chief arbitration judge, but not as a full political leader. This system bred distrust toward power-hungry leaders like Yaroslav, explaining his three expulsions from Novgorod.

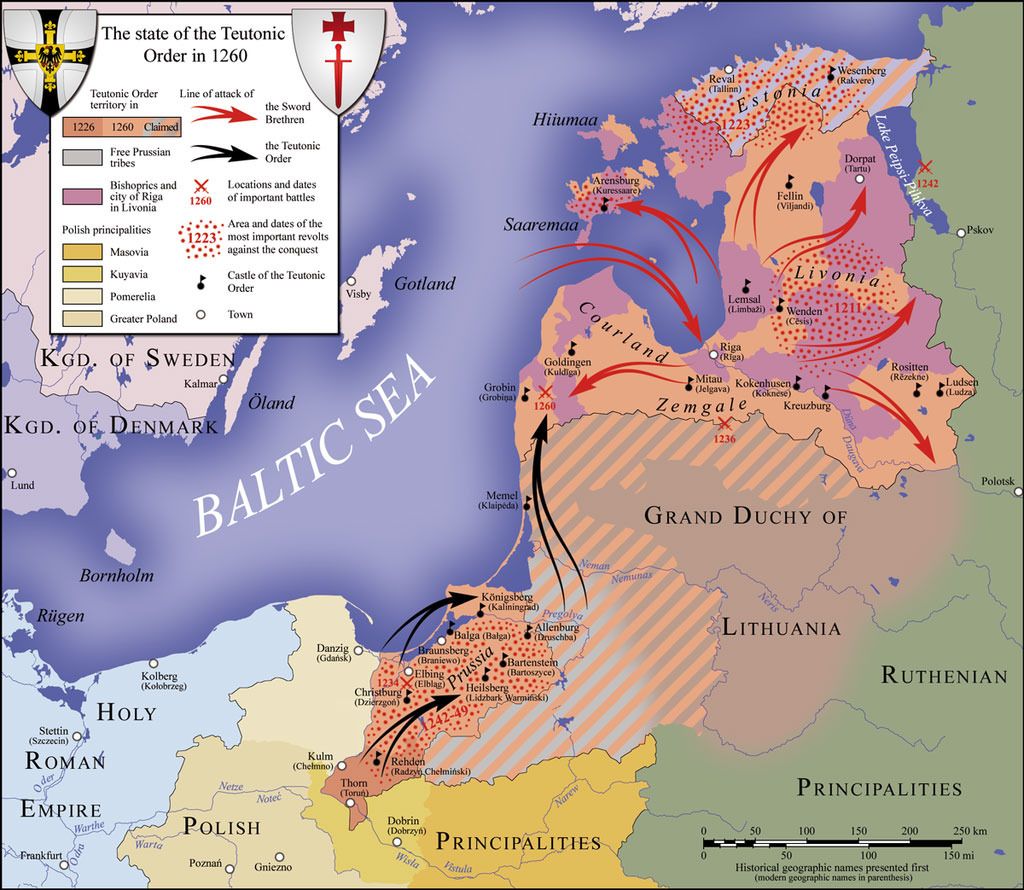

In 1236, the ruler left for a promotion in Kiev, declaring his son Alexander the prince of Novgorod. The young man was at least 15 years old at that time. By medieval standards, this was considered old enough for independent rule. Importantly, Alexander already had some combat experience: in 1234 he accompanied his father on a campaign to the Baltic against the German knights of the Livonian Order. The campaign culminated in the Battle on the Omovzha River (at Embach—Emajõgi in modern Estonia), where the combined Novgorod-Vladimir army decisively defeated the crusaders.

Today, only a narrow circle of medievalists recalls this battle, but it had far-reaching consequences. First, the Livonian Order suffered such heavy losses that they were forced to merge with the Teutonic Order, becoming its Livonian branch. Second, centuries later, one important detail of the Omovzha battle would “stick” to the deeds of the already adult Alexander.

Came, saw, conquered

In 1238, Alexander married the daughter of the Polotsk prince Alexandra. By 1240, he was considered a fully grown prince, and this year marks his first major event—the Battle of the Neva against the Swedes, traditionally dated July 15 in Russian history.

Among historians, there are two views on the 1240 battle. According to the classical concept, Alexander defeated a large enemy detachment of no less than 5,000 warriors at the mouth of the Izhora River. The invading Swedes, blessed by the Pope, planned to capture and Catholicize the northern Russian lands. Therefore, the young prince’s victory saved his compatriots from foreign domination. The alternative view sees the battle as one of many skirmishes between Swedes and Novgorodians in the frontier separating them: modern Finland, Karelia, and the Leningrad region of Russia.

The local nature of the July 15, 1240 battle is confirmed by the indifference of contemporaries. The fight at the mouth of the Izhora was reported—rather briefly—only in the Novgorod chronicles. Contemporary authors from other Russian principalities or the Swedish “Eric’s Chronicle” did not mention such an event at all. Assuming Scandinavian bias is doubtful—chroniclers at that time recorded everything, including events unfavorable to their suzerains. For example, the Swedes thoroughly described how in 1187 Novgorodian pirates raided Sigtuna, the ancient capital of their kingdom.

Supporting the hypothesis is the fact that in the first half of the 13th century, Sweden was embroiled in its own civil strife complicated by conflict with neighboring Norway. It is doubtful that under such conditions the Scandinavians gathered and sent by sea to distant Novgorod an army of 5,000 warriors—a large army by medieval European standards. Finally, the fact that Alexander acted on the Neva with only his own squad supports this concept. Against a multi-thousand army, the young commander would hardly have acted without gathering a militia and military help from neighboring principalities.

Most likely, the Battle of the Neva was not a full-scale battle but a brief skirmish involving a few hundred warriors. Moreover, many “canonical” details of this clash in Russian historiography turn out to be additions by authors living centuries after the event.

For example, only from the 15th century did Russian chroniclers claim that the Swedes at the Neva were commanded by Jarl Birger Magnusson—a major figure in local mid-13th century history, the de facto ruler of the kingdom and founder of a new dynasty. Out of nowhere arose the story of his duel on the Neva personally with Alexander—with the Novgorod prince naturally emerging victorious: “he stamped a mark on his face with his sharp spear.” Interestingly, in 2002, Swedish scientists found evidence of a serious injury under Birger’s right eye when studying his remains, but it is not at all certain that Alexander inflicted it. After all, Birger fought many opponents during his restless life—the list of potential assailants would be impressive.

If we discard the later chronicle “layers,” the picture emerges as follows. In the summer of 1240, a small group of Swedish adventurers landed at the mouth of the Izhora River into the Neva, near the borders of modern St. Petersburg. Their real goal was to plunder the indigenous Finnish inhabitants; at most, to establish a foothold in the region. But the local elder Pelgusy (Philip), a baptized Orthodox and tributary of Novgorod, informed his patrons about the uninvited guests. Alexander decided to act with a small force and reached the Swedish landing site with a squad of professional warriors within a few days. The Izhorians helped the Novgorodians approach the enemy unnoticed and launch a surprise attack, with Nevsky himself leading the assault. Taken by surprise, the Swedes abandoned their camp and retreated on their ships.

In any case, Alexander proved himself an exemplary medieval leader: intolerant of the plundering of his tributaries and swift in punishing border violators. However, in Novgorod, the military victory provoked fears among local “oligarchs” of the triumphant prince’s possible authoritarian ambitions. After a series of conflicts, the young prince left the city before the end of 1240. However, he soon returned there.

Pskov-style Eurointegration

The story around Alexander’s 1241-1242 campaign against the Teutonic Order (more precisely, its Livonian branch) is mythologized just like the Battle of the Neva. In Russian society, largely thanks to the famous film by Sergei Eisenstein, a false image of these knights has taken root. It is commonly believed that their order was originally a purely anti-Russian and anti-Orthodox force, a kind of precursor to the armored columns of the Wehrmacht.

In reality, the main enemies of the German crusaders in the Baltics were the local indigenous peoples loyal to their native polytheism. Since the 1180s, two military-monastic orders operated here: the Teutonic and the Sword Brothers, which merged after the 1234 disaster on the Omovzha River. For half a century, the knights, with varying success, reclaimed territories from pagans and built new fortresses and towns. The Russians were not targets of Catholic proselytism. To the crusaders, the “Ruthenians” were the lesser evil compared to the pagans: yes, schismatics, yes, enemies of the true church—but still Christians of some sort.

However, as the order expanded deeper into the Baltics, the knights increasingly clashed with the Russians, who considered the natives their tributaries. The crusaders, in turn, accused the Russians of inciting uprisings among the Estonians, Livonians, and other tribes. By the late 1230s, relations between the sides had deteriorated. In 1240, the Livonian army, with participation of Danes and pacified natives, marched eastward—against the land of Novgorod.

However, the crusaders did not seek to Catholicize the Russians but only to secure the western part of Novgorod lands. Specifically, they were interested in Pskov: in the early 13th century, this Russian city came under the control of a more successful eastern neighbor. Some Pskovians accepted the new status, while others believed it better to come under the Order’s aegis. The crusaders heard this signal and went to Pskov, accompanied by a relatively legitimate ruler—the subject was Yaroslav Vladimirovich (in German sources — Geropolt), son of the exiled Pskov prince.

In autumn 1240, the order’s army under Landmeister Andreas von Velven sequentially captured the border town of Izborsk, defeated the detachment of Pskov’s voivode Gavrila Gorislavich, and besieged Pskov. After a week-long siege, the head of local Eurointegrators, Tverdilo Ivankovich, surrendered the city to the knights and concluded a treaty under which the new owners promised to protect the Pskovians from Novgorodians.

But this annexation significantly shifted the balance of power in the region. Novgorod was now only a day’s march from the crusaders and therefore decided to reclaim Pskov.

Battle on the Ice, but without ice

The situation seemed favorable for a new victory of the knights. Especially since, as we remember, Alexander was absent from unstable Novgorod at that time. But facing the threat of the crusaders, the city’s best men persuaded the commander to return. In the winter of 1242, the prince gathered an army and marched west. He relatively quickly liberated Pskov with Izborsk (the Germans left a minor force there) and captured the fortress Koporye built by the knights; the Novgorodians destroyed the fortification, and its garrison of Chud—ancestors of modern Estonians, allies of the Order—were notably hanged.

After that, Alexander rewarded his troops and the arriving Suzdal allies by giving them the right to plunder the Dorpat bishopric—a friendly Livonian entity in eastern modern Estonia. Such a decision fully corresponded to medieval ethics: any war had to bring material benefits to the fighters. The crusaders logically stood up to defend their allies. And on April 5, 1242, the decisive battle took place on Lake Peipus, known as the Battle on the Ice.

Modern historians cautiously estimate the actual number of participants in the battle near the modern Estonian village of Mehkorkma. At most, the crusaders—with auxiliary units from indigenous peoples—numbered no more than 3-4 thousand, while the Novgorodians with Suzdal allies and local militias numbered a maximum of 6-7 thousand.

And the main detail of the battle as perceived by a 21st-century person—the supposedly knights sinking through the ice under the weight of their armor—was imagined by later generations. Neither German nor Novgorodian contemporaries mentioned that the battle took place directly on the ice.

The author of the “Livonian Rhymed Chronicle” wrote directly that “the bodies of the slain covered the entire field.” Apparently, by the 18th century, Russian historiography had mixed the circumstances of the battles on Lake Peipus and the aforementioned battle on the Omovzha. There, the Novgorodians really drove the knights onto the ice, as chroniclers wrote shortly after the event: “And as the Germans were on the Omovzha River, they broke through there, and many drowned.” Only in the 19th-20th centuries did the pseudo-archaic name “Battle on the Ice” become generally accepted among historians.

In reality, the Livonians’ defeat on Lake Peipus was not due to fragile ice. Velven underestimated the enemy’s strength and decided to break through their ranks by a wedge-shaped heavy cavalry attack. Alexander deliberately weakened the center of his army and strengthened the flanks—the knights' vanguard was encircled, and their comrades preferred flight to battle. As a result, the Novgorod-Suzdal army won a convincing victory. Russian chroniclers wrote of 400 dead and 50 captured Germans, “and countless Chud.“ German authors acknowledged the death of twenty and capture of six knights—still a lot, since these were only full members of the order, roughly speaking, army officers.

After Lake Peipus, the crusaders concluded an unfavorable peace with Novgorod, renouncing Pskov and other conquests. Alexander did not abandon the active defense of his state’s western borders. At least in 1245, he undertook a successful campaign against the troublesome Lithuanian raiders. During the campaign, the prince defeated enemy detachments at least three times. But the ruler’s main talent was not so much military valor as the ability to choose his enemies.

Horde vassal by circumstances and reluctant anti-Western

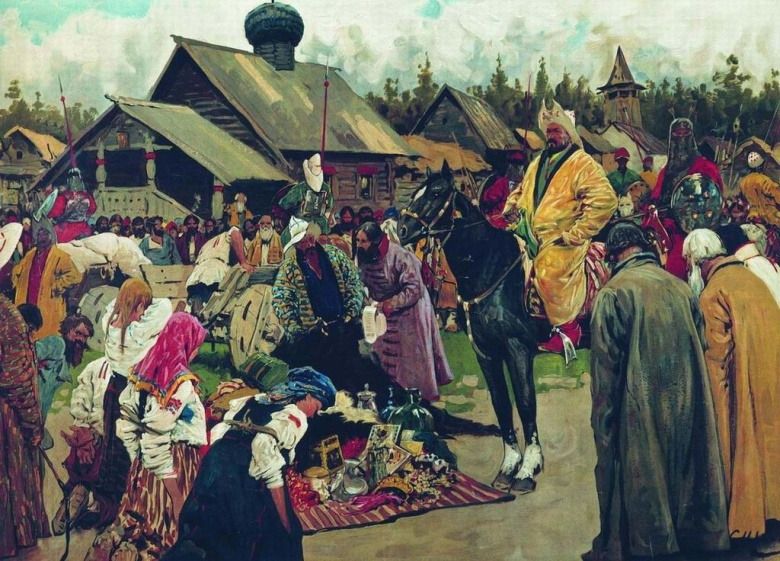

In 1237-1240, the Mongols attacked historical Rus (in two stages: first the northeastern principalities, then the southwestern ones). Chronicles unequivocally testify that contemporaries perceived the events of the late 1230s not just as a series of military defeats but almost as the end of the world, a heavenly punishment for the sins of the Russian people.

Archaeological excavations confirm the chroniclers’ accuracy. During the invasion, Batu Khan’s Mongol army (Batu) numbering no less than 40-50 thousand horsemen destroyed 49 of 74 major settlements in various principalities. More than half of them never regained their former significance or were never revived at all. Yes, the northwestern lands, including Novgorod, avoided the steppe invasion due to remoteness. But Alexander, judging by his later decisions, clearly understood the scale of the catastrophe. The key goal of his subsequent policy was to prevent the Mongols from entering Novgorod at all costs.

However, in the 1240s, all surviving Russian princes realized that in the new reality they would have to come to terms with the rule of the nomads. The new order meant receiving yarlyks (patents) to rule and paying substantial tributes (up to 10-15% of the principalities’ incomes). The imposed tribute further devastated Rus, as archaeologists confirm: from the mid-13th century, trade, crafts, and agriculture declined in most lands, and stone construction ceased for almost a century.

To obtain permission to rule from the conquerors, princes initially had to travel to Mongolia itself—to Karakorum, the capital of the still united vast empire. Over time, the nomadic superstate split into several parts. Rus was subject to the so-called Ulus of Jochi, better known as the Golden Horde. In 1243, the first yarlik for grand princely rule in Vladimir was given by the Mongols to Alexander’s father, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, who had previously avoided active resistance to the invaders.

Then other Russian rulers also went to the conquerors, obediently following Mongol diplomatic protocol. This included passing between fires, bowing to a statue of Genghis Khan, and other clearly pagan rituals. Between 1247 and 1263, Alexander Yaroslavich personally underwent these practices.

The Russian prince traveled four times to Batu Khan in the Horde capital Sarai (near modern Astrakhan) and once made a forced transcontinental journey to Karakorum. He found common ground with the Mongols, skillfully maneuvering among different centers of power within the steppe peoples—at least for a time.

By the way, Alexander’s father did not succeed in this skill. In 1246, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich died under strange circumstances during a visit to Karakorum—most likely, the Russian prince crossed local court intrigues and was poisoned. The yarlik for ruling Kiev—that is, nominal leadership of Rus—was then given by the Mongols to the deceased’s son, Alexander. But Nevsky did not go to the de facto destroyed “Mother of Russian Cities” and, as the prince of Kiev, simply returned to whole, familiar, and quite prosperous Novgorod.

At the same time, the prince for a long time did not exclude the possibility of fighting the nomads. In the late 1240s, Alexander exchanged several letters with Pope Innocent IV—a pragmatic man tolerant of Eastern churches. The Catholic hierarch promised unclear support to the Orthodox politician in the struggle against the steppe barbarians in exchange for submission to Rome. But the Novgorod prince, lacking clear guarantees of help, diplomatically avoided a definitive answer. The correspondence apparently died out by itself—without an explicit break but also without concrete results. Therefore, Alexander had to strengthen ties with the Horde. And this implied unpleasant compromises.

In 1252, at least with the prince’s neutrality, the Mongol commander Nevruy made a punitive campaign to northeastern Rus. The expedition cost the rule of two of Alexander’s brothers, who rebelled against the steppe peoples—the Vladimir prince Andrey and Pereslavl prince Yaroslav—and the elder relative did not come to their aid. In 1257, Alexander personally led the suppression of an anti-Mongol uprising in Novgorod (nominally ruled then by his eldest son Vasily). The townspeople, outraged by the tribute payment, persuaded inexperienced Vasily to their side, killed Alexander’s loyal Novgorod officials, and tried to raise an anti-Mongol rebellion. But the old prince roughly suppressed the revolt before news of it reached the nomads.

Chroniclers acknowledged that Alexander notably executed the ringleaders of the rebellions and for ordinary participants “cut off noses for some, gouged out eyes for others.”

Apparently, the prince’s main political capital was his good personal relationship with the Golden Horde ruler Batu Khan. Centuries later, this would spawn baseless legends about either adoption or brotherhood between the Russian prince and some Chinggisid. But in 1256, the steppe monarch died, and the Novgorodian never found a new reliable patron in the Horde. In 1263, the 42-year-old politician and military leader died on the way back from the Horde under strange circumstances, probably poisoned. Alexander Yaroslavich either backed the wrong side in internal Horde feuds, refused to participate in a new Mongol campaign to Asia, or was suspected of some other disloyalty.

Critics of the prince might pathetically conclude: here is the deserved end for a servant of conquerors. But did he have real alternatives? Most likely not. In the 1250s, even the Galician prince Daniel Romanovich, almost the only Russian ruler consistently fighting the yoke, swore allegiance to the Mongols. Having realized that Europeans could not help and the nomads were invincible, the “Westernizer” Daniel recognized the Steppe’s power and, just like the “pro-Horde” Alexander, began paying tribute.

Prince born after death

In a way, Alexander was doomed to posthumous glorification. Ironically, he ensured it with probably the most mundane of his decisions. Shortly before his death, the prince sent Daniel, the youngest of his four sons, to rule the town of Moscow—a place so insignificant that it previously had no princely throne. Thus, Nevsky, unknowingly, became the progenitor of the future dynasty of the united Russian Tsardom.

At the same time, the posthumous cult of Alexander Yaroslavich began to develop already in the 13th century. In the 1260s, the metropolitan Kirill III, close to the prince, ordered a hagiographic tale to be written about the deceased. In it, the main character appeared as meek, gentle, and devout—without any executions of prisoners or gouging out eyes of rebels. The authors claimed that Alexander took monastic vows before death according to princely tradition.

The anonymous author reinterpreted several real episodes from Alexander’s life. Thus, the cautious and mutually polite correspondence of the prince with the Roman pope turned into persistent attempts by the “Latins” to convert the Rus to Catholicism, followed by a decisive refusal: “We know our good faith; we will not accept foreign teachings.” At the same time, the battles on the Neva and Lake Peipus began to be exaggerated. Local clashes were presented by one author or another as battles decisive for all Russian lands as a whole.

In the 14th century, the hagiographic tale became the basis for venerating the prince as a saint in the Russian North. Posthumously, he received the nicknames “Nevsky” and “the Brave”—apparently not used during his lifetime.

In 1547, the Church officially canonized Alexander as a holy warrior for all-Russian veneration. The decision coincided with preparations for the Livonian War—against the same Swedes and Germans—under Ivan IV the Terrible. At that time, the Russian Tsardom lost the battle for the Baltic, but the cult of Nevsky as an invincible warrior persisted.

In the early 18th century, the veneration of Alexander was reinforced by one of the most irreligious rulers in Russian history—Peter I. Under him, a special monastery appeared in the new capital Saint Petersburg in memory of the victor over Germans and Swedes, the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. In 1724, the presumed remains of the medieval ruler were solemnly transferred there. Nevsky was also greatly loved in 19th-century Russia—at least because almost the entire century the country was ruled by namesakes of Alexander.

Finally, in the 1930s, the image of the ruler as an unyielding patriot and valiant commander was modernized by the iconic film “Alexander Nevsky” directed by Sergei Eisenstein.

The creators of the film, in the spirit of Stalin’s era, ignored the theme of religion but creatively played with the anti-Western narrative, gifting the viewer a pseudo-archaic novelty. Just consider the “dog-knights,” quickly becoming a common epithet in Russian tradition for the Teutonic Order.

In the 13th century, German knights in Rus were never called that. The pejorative arose in the USSR due to an incorrect translation of a trope favored by Karl Marx—Reitershunde —something like “band of riders” or “gang of robber knights.”

Prince Alexander himself is portrayed in Eisenstein’s film as a simple, straightforward leader close to the people, speaking in aphoristic phrases in the spirit of Taras Bulba. Ironically, despite the “Soviet” Nevsky’s irreligiosity, many of actor Nikolai Cherkasov’s lines have Christian origins. “Whoever comes to us with a sword shall perish by the sword!” is an obvious paraphrase of the gospel “For all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (Matthew 26:52).

***

So who was the real— not Eisenstein’s, Putin’s, or, God forgive, Ponasenkov’s—Prince Alexander Yaroslavich? Comparing with historical facts, most praises and accusations against the prince turn out empty. Alexander began cooperating with the Mongols almost 10 years after their invasion, when most Russian rulers had already taken this path. At least eight other princes had already gone to pay homage in the Horde before him.

This politician physically could not “separate” Rus and Europe (nor submit Rus to the West) because he never actually ruled all the lands of historical Kievan Rus. Alexander did not make the notorious “civilizational choice” between East and West: in the 13th century, neither existed in the modern sense, and the very concept of “civilization” would be extremely difficult for a medieval person to grasp. The Novgorod prince simply refused an alliance with dubious partners without obvious prospects in favor of accepting the status quo and attempts to coexist with the only real power.

In short, Alexander Nevsky is not an Orthodox fanatic, not a militant anti-Western, and not a lover of Asian despotism. As historian Igor Danilevsky aptly put it, he was “a normal ruler of his time: when he can, he resists; when he cannot, he makes peace.” Or, in the more concise characterization of Anton Gorsky, “a calculating but not unprincipled politician.” In this capacity, the memory of the prince who lived 800 years ago is more than relevant for modern Russia. Especially considering that this very person was the first among Russian rulers to voluntarily renounce power over Kiev—a still unattainable example for the current leadership of the Russian Federation.

Main sources of the article:

- Danilevsky I.N. “Alexander Nevsky: Paradoxes of Historical Memory”

- Gorsky A.A. “The Mongol Yoke and Its Consequences”

- Dolgov V.V. “The Phenomenon of Alexander Nevsky: 13th Century Rus Between West and East”

- Zakharov O.A. “Relations of Alexander Nevsky with the Golden Horde in Russian Historiography”

- Kuznetsov A.V. “Battle on the Ice: Was It or Not”

- Libenstein A.I. “Alexander Nevsky and the Teutonic Order”

- Lurie Y.S. “On the Study of the Chronicle Tradition about Alexander Nevsky”