Support the author!

Personal experience: a journalist goes to work at a cemetery

Khovanskoye Cemetery, January 27, two o'clock in the afternoon. A group of four people stands by a black minivan. They are dressed in identical black jackets and hats. Next to them, on metal trestles, is a four-sided coffin with no handles. People in work uniforms are nailing the base of the coffin. About 5 meters from the coffin—just one grave away—stand several gravediggers, ready to take the coffin in their hands and lower it into the grave. We only need to cover those 5 meters. But three out of the four people in black take turns falling, bumping the bottoms of the coffin into the grave fences. Only the fourth one managed to stay on his feet. That was me.

The night before, there was a heavy snowfall in Moscow, and there is a lot of snow at the cemetery. The diggers have trampled a path in the shape of an “L,” just wide enough for a coffin, and we have to carry the coffin along this path, which is usually held by the sides. In this case, two people carry the coffin: one at the head, one at the feet, and the other two stand behind them to catch in case of a fall. You have to walk backwards.

The hardest part is turning on this L-shaped path. In season five of “Friends,” in “The One with the Cop,” there's a famous scene where Chandler and Rachel help Ross move a couch up a narrow staircase and get stuck at the turn. That's pretty much how we got stuck at the turn with the coffin.

While we walk along the path to the hearse, the diggers are already lowering the coffin into the grave. The foreman approaches the people, and someone from the mourners silently hands him money. We get into the hearse and leave immediately.

I have never liked funerals since childhood, but I could never explain to myself why.

On March 1, 2024, after Navalny's death, when his body was returned to his family and they were able to arrange a funeral, for some reason I went to Maryino and stood there in the crowd by the church where the funeral service was being held, but I didn't go to the burial itself because of my attitude toward funerals.

After that, I started following how the funeral business works in Russia—just reading specialized media.

In mid-January 2026, I got tired of sitting without a steady job and decided to see what vacancies I could find by searching for “ritual.” I found a sales agent position at the State Unitary Enterprise “Ritual” and a job in a funeral escort team at various sole proprietors.

Only one of the sole proprietors had an employer description:

“Hello, my name is Nikita, and I am a contractor for funeral escort teams at GBU Ritual (the largest funeral organization in Moscow and the Moscow region).

Our team is looking for young people/men who are understanding of the loss of loved ones of our clients. We would be happy to welcome you to our team!“

The duties of a team member include “carrying the coffin with the deceased from the morgue to the hearse and at the cemetery (crematorium), going to the church if necessary.” One job, the contractor promises, lasts from three to five hours. The candidate for this position is expected to “be able to show empathy, be punctual, have a neat appearance, adhere to the dress code, and be diligent.”

No experience required, part-time, physical work. In general, an ideal activity for a Russian creative intellectual.

Competitors of GBU, JSC “Ritual-Service,” owned by “funeral king” Oleg Shelyagov, write about escort teams like this:

“A professional coffin bearer is a strong and experienced man who knows all the nuances of his work. Thanks to his skills, the risks during the removal of the body from the home/morgue, its transportation in the hearse, and its movement to the place of the funeral service/burial/cremation are reduced to zero. Although some see working as a coffin bearer as a good side job, we entrust this responsible task only to proven professionals.

Many people do not see the need to order movers' services or, not trusting “ritual services,” turn to dubious sole proprietors. Unfortunately, this choice is fraught with problems: even a competent mover may not cope with the difficult task of carrying a coffin with the body of the deceased, so only trained people are chosen for this job.“

On the GBU “Ritual” website, there is no description of the escort team's work.

The escort team consists of four people—a foreman and three movers. The foreman communicates with the funeral agent and the hearse driver, calculates the route from the metro to the morgue, and contacts the movers. He also commands the movers during the carrying of the coffin and approaches the relatives of the deceased for a tip after the procession.

01/23/2026

On my first day at work, our team meets at one of the metro stations in the south of Moscow. We head to the morgue on our own, by bus, and before entering the morgue grounds, we change into uniform jackets. You need to attach a black-and-red armband with an elastic band to your sleeve, and a badge with the GBU logo to your chest. The badges have a crooked pin and don't hold well, so Gennady recommends buying a magnet to support the badge. He does not advise walking around the city with the armband:

- When all this stuff with Ukraine and the “Right Sector” started, some people could get the wrong idea, so don't. One time we forgot to take it off, and someone asked us what organization we were from. “From GBU Ritual!” I said. They looked at us so strangely!

However, after work, the foremen take away the armband and badge for safekeeping and for future teams.

- Our job is chill. The main thing is not to laugh loudly or swear. You can do your own thing, sit on your phone. You can sleep on the bus. If there are relatives there, it's better to sit further away so they don't see you. Everything else is optional, — the foreman explains the rules. — You can talk to the relatives, express condolences. The main thing is not to argue with them. You can help an old lady get on the bus, for example, or lay flowers at the funeral service. But it's not required. Our main job is different.

At the start of the order, the team must take a photo—to report to the contractor that the order has started and that they look appropriate. The photo must show the name of the place where the team is picking up the body, and the whole team must be visible full-length. The movers and foreman stand in a line, feet slightly apart like in the first position in ballet, hands on the stomach, with the left hand covering the right. Foremen pay special attention to this. Also, in the photo, the team must either all be wearing gloves and hats, or none at all.

Photography is forbidden in the morgue—there is a sign on the wall. Despite this, for some reason, we take our photo inside the building—apparently, we're an exception. After the photo, Gennady tells us what we have to do—carry the coffin from the hearse to the farewell hall, unpack it, put the lid on, and leave. The body is placed in the coffin by the morgue staff. In today's order, the funeral service takes place directly in the morgue—when it's over, the door to the mourning hall will open, and the team can enter.

- Once, we didn't notice when they opened the door, and the relatives anxiously peeked out: “We're all done!” — Gennady says.

The funeral service starts later than scheduled because the relatives were a bit late to the morgue. Gennady says that often happens.

While we wait for the service, he assigns us roles. Gennady and the other new guy carry the “head”—the part of the coffin where the person's head is. Usually, that end is wider on four-sided coffins. I and Vasya—another member of our team—carry the “feet.” Those who carry the feet also have to bring the lid to the coffin.

When the service ends, the team enters the mourning hall, and Vasya and I “stand by the lid”—on either side of the coffin lid. Gennady removes the flowers from the coffin, Vasya and I carry the lid, pass it over the coffin, hand it to Gennady and the other mover, and gently lower the lid onto the coffin. Then Gennady and Vasya screw the lid onto the coffin with special decorative screws. Depending on the shape of the coffin and lid, they are screwed in either strictly vertically or at a slight angle.

After the lid is attached, the team takes their places by the handles, stands for a couple of seconds in the pose from the photo (as a tribute to the deceased), then, at the foreman's command “Lift!” picks up the coffin and carries it to the hearse feet first. They load it, put the flowers nearby in the empty seats, and get into the hearse. The foreman takes a photo of the loaded coffin. We form a small wall, the relatives walk past us and get on the bus. We follow them, sit closer to the coffin so we're not visible, and head to

Yastrebkovskoye Cemetery in the Moscow region—one of four cemeteries still open for new burials. Most of the cemetery is empty and looks like a snow-covered field. It takes about an hour and a half to get there from the southern part of old Moscow—plenty of time to get some sleep.

At the cemetery, while the relatives of the deceased are processing the paperwork for the grave, the team takes a second photo report. With the grave documents, we go to the allocated plot, meet the diggers’ foreman, and unload the coffin onto the stands.

After the final farewell to the deceased, we lift the coffin, carry it to the grave, and hand it over to the diggers. They thread straps through the handles, run them under the coffin, and slowly lower it into the ground. The client with the documents stays at the cemetery, the rest of the family gets on the bus. The team sits with them. Two men pull out a small bottle of vodka, pour it into paper cups, and drink without toasting. After three cups, one of the men sits next to the foreman and hands him a 5000-ruble bill as a thank you for the escort.

The tip is split equally among all workers, including the driver. In Moscow, he drops us off near a metro station within the MKAD, and Gennady asks me and the other new guy if we liked everything.

- The job isn't hard, sometimes even interesting, — I reply, and add that I'm ready for new orders.

In the evening, a new foreman sends me the place and time for tomorrow's meeting. At the end of the message, he writes: “The note about 'appearance' is there for a reason, please be sure to have clean pants and shoes.”

01/24/2026

I was a little late, foreman Stepan and mover Artyom are waiting for me outside. As we walk from the bus stop to the morgue, Artyom briefly explains how to work with the crematorium, then discusses previous shifts with Stepan. They complain most about the lack of tips.

While waiting for the body, we sit in the hearse and warm up. I ask Artyom how often an escort team is present at funerals.

- It's a required service. This is GBU Ritual, the FSB covers them, it's all serious here, — he replies. I don't argue, just say that in my hometown there are no such services.

Soon Andrey—our third mover—pokes his head into the car and calls us for a photo. Judging by his Telegram avatars, he's a musician, sings and plays guitar. While Andrey smokes, a mover from another team comes up, asks for a cigarette, and asks about salary.

- Seventeen hundred, — Andrey replies.

- Eighteen hundred, — says the other mover. And asks us which agent we work for—he liked our uniform jackets.

He pauses for a drag and continues:

- Why don't we get robes? We could dress up as the Grim Reaper, create a special atmosphere. We're basically animators, just for adults. We could be like the band Behemoth.

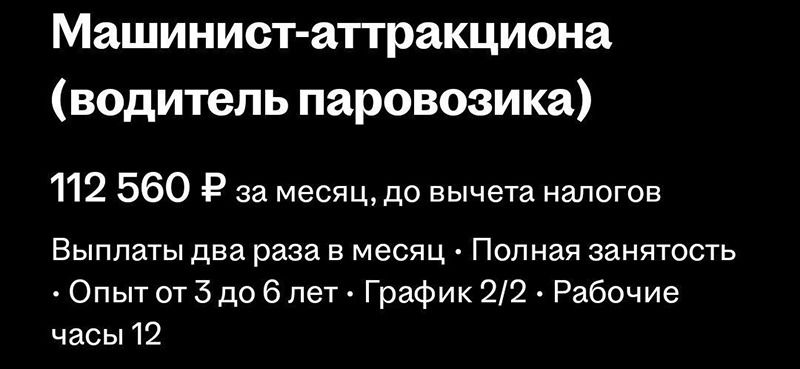

We warm up in the cramped anteroom of the morgue. Artyom scrolls through job listings, and at some point laughs in surprise:

- Children's train ride operator. Pays 120 thousand. “I work as a train operator!”

Stepan smiles silently but says nothing. Artyom is ready to work as a hearse driver—he says GBU “Ritual” is looking for drivers with category “B” licenses. Later, Artyom even discusses this with the hearse driver, but the driver says there are only a few such vehicles, and they're more often looking for category “D,” which allows you to drive buses.

Soon we bring the coffin into the mourning hall, wait for a relative to identify the body (a standard procedure for funerals), and then close the coffin. Today the funeral service will be held in a church. This time I'm at the “head,” and before the lid is brought, I have to straighten the shroud on the deceased. Some call it a blanket. I accidentally cover the face, but Andrey, who is also at the “head,” uncovers it again.

Today we are “escorting” a woman with the surname of a famous lawyer. Her face is heavily covered with makeup. She looks like a doll and a wax figure at the same time. She will be cremated today.

The funeral service is held at the Church of John the Baptist at Khovanskoye Cemetery. As we approach the cemetery, Artyom points out the white smoke from the crematorium—a sign that we're almost there. We carry the coffin into the church—have to climb a few steps—and bring it to the altar, where two pairs of wooden trestles for coffins are set up. Another person will be buried along with this deceased. Artyom and Andrey open the coffin, then take the lid outside and leave it by the church entrance. A few minutes before the service, our team prepares candles for the family. We put the candles into small paper holders with a slit and hand them to people around the coffin. Foreman Stepan helps put flowers in the coffin. The second team brings in their coffin, and a few minutes later the service begins.

- Some priests do the service quickly, some get into it and can sing for half an hour, or more, — complains Artyom. — Old Believers can do a service for an hour and a half.

Artyom doesn't like long jobs and isn't thrilled about this side gig. He has a main job with a “week on, week off” schedule, so he does coffin escorting as a side job. I listen to the service and flip through the books for sale in the church, especially the Psalter for the Dead with commentary.

At some point, the priest takes earth in his hands and sprinkles it on the deceased, making a cross with the soil. For the “committal,” the team brings the lid back into the church and waits for the service to end. We don't remove the flowers from the coffin, that's not necessary for cremation. We wait for the foreman's command, lift the coffin, and carry it to the hearse to go to the crematorium. The family of the deceased goes with us to the crematorium.

Khovanskoye Crematorium has four ovens and three farewell halls. Up to 70 cremations can be performed there per day. About ten hearses wait by the crematorium for their turn for cremation.

The foreman and the client go out first to start the paperwork needed for cremation. After a while, he calls us to take a photo. We're photographed by a member of another team, in a classic coat and white gloves. He's a mover from the elite team. To get into their team, you have to meet certain physical requirements, Artyom explained. He also says they are officially employed according to the Labor Code, unlike us.

After the photo, the foreman tells us the client has reserved a cremation slot, so we won't have to wait long. All this time before the body is taken out, the team discusses their jobs:

- The best jobs are when the funeral service is at the crematorium. Load the body, and you're free. Fifteen minutes of work, — Andrey muses.

- Where have you seen jobs like that? Besides, you have to wait your turn. Once we waited several hours.

- How much time usually passes between bringing in bodies? — I ask.

- Ten minutes, if there's no long farewell. If there is, then fifteen, with a service even longer, — Artyom replies.

- I wonder if there will be “tea” today?

- I hope so, I've had two “bolts” in a row.

A “bolt” is when there is no tip.

It's our turn to bring in the body. The bus pulls up closer to the farewell hall doors, we take out the coffin, and carry it to the pedestal, which disappears behind a curtain—probably onto a cart or conveyor to the oven.

The family returns to the bus. Stepan approaches the client to say goodbye:

- Once again, accept our condolences, and if you are able, please thank the team.

She nods to Stepan, and they walk together toward the bus, where all the family have already boarded. The client also gets on the bus and closes the door. The bus leaves.

- You give them your whole heart, try to help, and they do this! Stupid idiot, — Artyom complains.

- I told her, like, thank the team, and she said, “I understand,” and left. What the hell. Went to the driver, gave the number, said, maybe in the end something will come our way.

We walk toward the nearest bus stop to get to the metro. Artyom and Stepan walk ahead, discussing “bolts,” Andrey and I follow behind in silence.

In the metro, Stepan forwards the driver's message: “ Thank you! Goodbye! Well, I told her Goodbye too!” with a picture of a fig sign.

01/27/2026

Today we're picking up a body from the forensic morgue at the hospital in Kommunarka, which became famous nationwide during the coronavirus pandemic. The foreman's name is Gleb, he's 26, has been working for nine months, and was promoted from mover to foreman in just a few weeks. We wait for the second mover—Vasya from my first day—and head toward the morgue. The third colleague is waiting for us inside. On the way, it turns out Vasya has also been working for nine months, and the contractor offered him a foreman position, but he refused because the extra pay was too small.

As we walk to the morgue, Vasya and Gleb have the classic conversation—discussing their jobs and tips. Gleb says his recent jobs have been unlucky; for example, he recently escorted a woman who was in a bag in the coffin, and her boss buried her—she had no family.

Vasya replied that he had a job where they buried a SVO participant—or rather, his leg.

- There was a SVO guy, in some strange robe, not a bag like usual, and a black leg was sticking out. The smell was terrible.

At some point, Gleb shows me a video where a boy films his grandmother's corpse and jokes about her. Professional humor of the funeral industry.

Unlike other morgues I've been to, at Kommunarka they check passports at the checkpoint. Behind the glass, a young woman in a vintage knitted sweater listens to the phrase “GBU Ritual escort team” three times, gives us paper passes, and we enter the hospital grounds. There, we are met by a mute mover named Pyotr, nicknamed “The Boulder.” We put on our badges, armbands, and go to take a photo.

This time, the coffin is by the doors of the mourning hall, not in the hearse.

Cheap four-sided coffins covered in brown cloth are called “chocolates” by the movers—today we're calling it a “Snickers.”

- And the coffin has no handles! — the foreman notes. — We'll have to carry it from the bottom. Well, at least it has screws.

The hearse driver also notices the lack of handles and asks if we had porridge for breakfast—meaning we'll have to work harder today.

After a brief identification, the relatives go to the hearse, and we head toward Khovanskoye Cemetery—first there will be a funeral service, then the burial. The family sitting in the hearse across from me quietly discuss benefits for SVO participation.

01/28/2026

Most of the time on the job, the team spends waiting. Depending on the mix of movers, the wait is either brightened by stories about other jobs or everyone is just doing their own thing. Today's job starts outside City Clinical Hospital No. 20. At this hospital, the escort team is only allowed in half an hour before the scheduled time. After the morgue, we'll have to go to the Nikolo-Arkhangelsk Crematorium.

For the first half hour, we stand by the checkpoint, and movers Vasya, Danya, and foreman Valery tell different stories from their jobs. Of course, they start by talking about money:

- What do they give for SVO funerals?

- For SVO funerals, it's usually 5-10 thousand. But yesterday we didn't get anything.

- We recently buried a cemetery director's relative, he was so angry, made them redo the corpse's face. They spent hours on it in the morgue. But he left a big tip, gave some to the team, and gave a lot to the driver.

I quickly start tuning out the money talk. Luckily, soon they start talking about colleagues.

- Remember that guy whose pants fell down on the job?

- There was also someone who showed up once and then disappeared for a month.

- He just went on a bender.

At some point they remember that someone's coffin bottom fell out on a job.

- That was my job, — says Vasya. — We were doing an exhumation, we lifted it, the bottom fell out, and so did the body.

- No, you also had a SVO guy fall out one time.

- He didn't fall out, he leaked. We were carrying him on our shoulders, it got on my jacket, on my pants. I almost threw up everywhere.

There's a limousine by the morgue instead of the usual bus.

- They've got a Cadillac hearse, must be rich clients. Hope the tips will be big too.

That's Danya speaking. Today is his tenth job. He's a student, studying to be a customs specialist. He doesn't have another job yet.

- Maybe I'll work as a taxi driver in the summer. Now I have holidays, and enough time just for escorting.

- How do you like this job?

- Some people think this job is for cleansing the soul. I don't know, I'm not a believer, I don't care.

A man enters the mourning hall. A woman asks him how he's doing:

- Not great. My father died, — the man replies with a cheerful face. That's our client.

The funeral agent introduces him to the foreman, then takes the foreman aside and says the client won't go to the crematorium.

- I don't know if you do this, but maybe you can arrange for the body to be loaded and received there? Then you won't have to go.

- No, that won't work. We have to go.

We have to go to take a photo at the crematorium. Without that photo, the team won't get paid. Valery says we need to carry the coffin on our shoulders to make sure we get tips. Someone jokes we should walk up the ramp so we carry it longer and get more tips.

The funeral service begins. We take turns waiting outside for it to end—you can't go through the main hall of the morgue to the mourning hall. When the priest starts singing “Eternal Memory,” we all go to the hall entrance. Gennady says we need to take the coffin on our shoulders as soon as we leave the hall.

The lid is screwed on, Gennady commands “Lift!”, we leave the hall, and Gennady whispers that there will be no shoulder carry. We load the coffin into the hearse and step aside. The foreman “makes an approach” to the client. He returns disappointed:

- Bolt. “Thank you very much, you are real professionals.”

- Cheap bastard. It's obvious he's wealthy.

- That's why he's wealthy—he doesn't give tips!

- He doesn't seem too upset. His father just died.

We walk toward the checkpoint. Since the coffin is not being taken in the bus, we have to get to the cemetery on our own. The contractor orders us a taxi. While we wait for the car, the guys keep complaining about the client not giving a tip. When the relatives and loved ones of the deceased walk by, the team barely lowers their voices.

At the cemetery, we meet the hearse driver. He also complains about the client who didn't leave a tip. This man is clearly Russian, but he compares him to “stingy nationalities”:

- Armenians are just like Jews. Even worse. They never give tips.

- And yet they all come in expensive cars, hire professional mourners.

- One time they gave a tip. Crumpled bills, fifteen hundred.

The courier quickly processes all the documents, the hearse pulls up to the crematorium, the crematorium staff roll a cart closer to the limousine, we carry the coffin a few meters, leave it with the staff, and leave.

On the evening of January 28, foreman Dima writes to me, asks if I've had any SVO funerals, and adds, “it's going to be 'fun'))”.

All names and personal circumstances of the characters have been changed.

Photos by Nikita Zolotaryov

TO BE CONTINUED