Support the author!

In October 1983, the USA invaded Grenada — and it was a true special operation

The story of how to seize a foreign country in three days and convince its people that their lives have improved

In October 2025, the phrase “small victorious war” can only be taken sarcastically. After everything we've witnessed over the past three and a half years, it seems madness to believe that a specific political problem can be solved militarily. And that the ultimate gain would outweigh the costs incurred.

However, even in the relatively recent past, there are examples of politicians successfully carrying out genuine special operations. Within a short time and with minimal losses, they managed to emphasize their country's international weight. Meanwhile, all external adversaries were left with nothing but powerless resentment.

Forty-two years ago, the American invasion of Grenada unfolded precisely in this way. The U.S. military did indeed capture a foreign country in three days, avoiding serious foreign policy repercussions. More than that, the Grenadians themselves accepted the foreign intervention without negativity; the date of the Caribbean island’s intervention is still celebrated as a national holiday. Why did this happen?

A Haphazard Invasion

On the Friday evening of October 21, 1983, U.S. President Ronald Reagan went away for the weekend to Augusta, Georgia. The head of state seemed to want to hide among the fields of the local National Golf Club, away from all the twists and turns of foreign policy. In the early 1980s, the Cold War was heating up seriously. The Soviet Union, the United States, and their respective allies seemed to have forgotten about the recent “detente” and were escalating their confrontation.

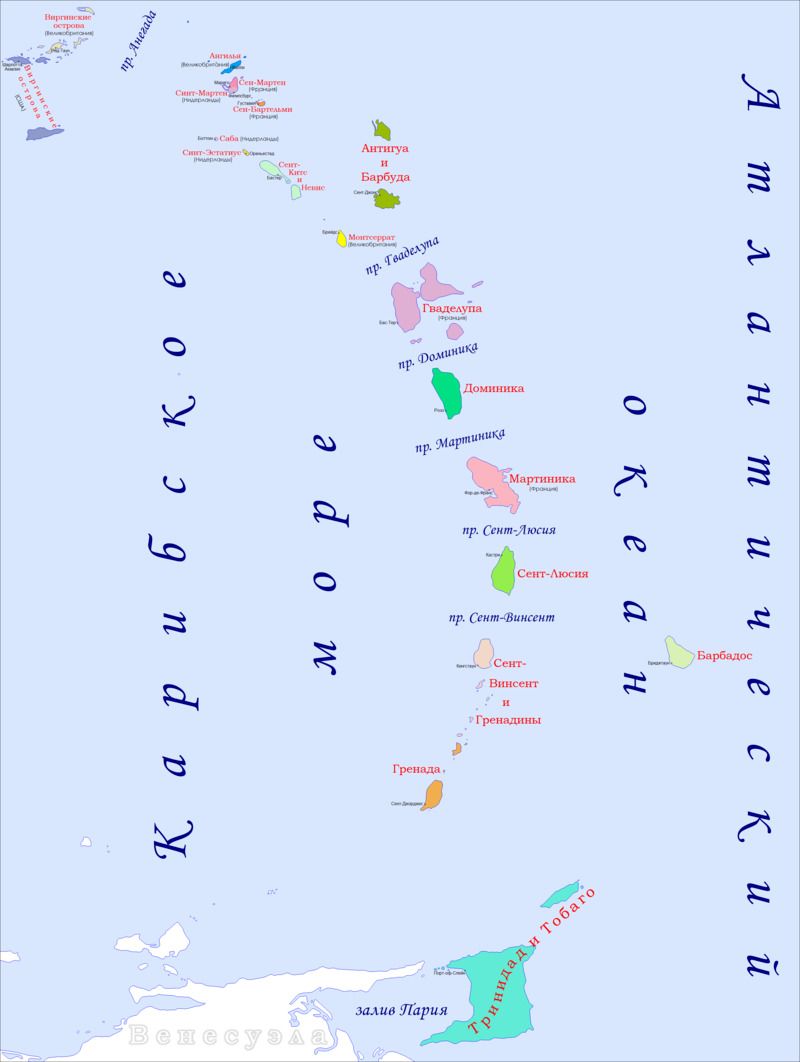

Conflicts flared up here and there: in Nicaragua and Afghanistan, Angola, between Iran and Iraq, the Falkland Islands, and, finally, the chronically troubled Middle East. And in mid-autumn 1983, this list was unexpectedly joined by tiny Grenada in the southern Caribbean Sea. This small island state was barely larger than an average American city such as Atlanta or Detroit, with a population of just over 100,000. What kind of conflict could possibly be hidden here?

Since 1979, Grenada had been ruled by a Marxist government sympathetic to the USSR after a coup. Republican circles in the U.S. and Reagan himself could not ignore such a neighbor — a second Cuba was strengthening right before their eyes and just next door. In 1983, however, things on the island seemed to be moving in Washington’s favor. Rumors circulated that the young Grenadian Prime Minister Maurice Bishop had reconsidered his beliefs and was leaning away from the former pro-communist course. But on October 19, the U.S. received a disheartening piece of news. Bishop was deposed and executed along with his associates — all betrayed by former comrades opposing the reforms.

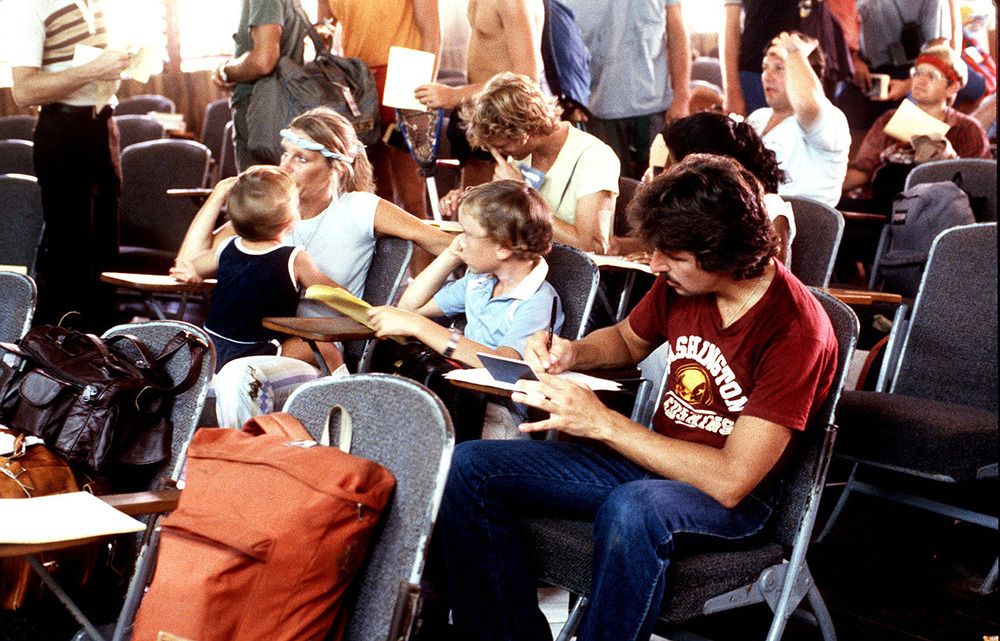

It became clear that a new coup had taken place in Grenada, and real power was now in the hands of a completely reckless junta. At the same time, there were 600 U.S. citizens on the island — mostly students benefiting from affordable higher education in English. The Reagan administration was alarmed: would the new Grenadian authorities take Americans hostage, as had happened four years earlier in Iran? No one in the White House knew what to do next. Reagan decided to spend a couple of days hitting golf balls around Augusta — hoping for inspiration.

However, the president’s brief rest in Georgia was overshadowed by two incidents. The first was more of a tragicomedy. A local unemployed man, having heard about the president’s visit, decided at all costs to complain to the guest about his misfortunes — even taking hostages in a small shop near the golf club, demanding to speak with Reagan. The man’s mother, who arrived hurriedly, managed to persuade her son to surrender peacefully to the police.

The second incident was far more serious. On October 23, the U.S. learned that in Lebanon, where a civil war had been raging for nine years, Islamist fanatics attacked the barracks of American peacekeepers. Two hundred and forty-one Marines died within moments — an event unprecedented even in the ill-famed Vietnam War. Reagan’s team risked being seen by the world as foreign policy failures, like their predecessors, the administration of Democrat Jimmy Carter.

After brief consultations with Vice President George H.W. Bush, Secretary of State George Shultz, and National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane, the president decided to counterbalance the Lebanon tragedy with a triumph in Grenada. He made the decision, although even the former actor did not look like a victorious leader at that moment.

It is obvious that the past 72 hours have taken their toll on the president. Exhausted and detached, even old, for the first time during his presidency, he stepped from the helicopter onto the South Lawn of the White House and reached for his umbrella — it was pouring rain. It was 8:30 a.m. Six hours earlier, the president had been awakened with the first news of casualties at the Marine headquarters.

- The New York Times, October 25, 1983

On the evening of Sunday, October 23, Reagan officially approved the plan Urgent Fury (“Burst of Fury“), a military operation in Grenada. De facto, it was an invasion of a sovereign state aimed at changing its government. Any miscalculation here threatened the Americans with a second Vietnam — but it ended up being arguably the most glorious victory for the U.S. during the entire Cold War. Why?

The Most Loyal of Revolutionaries

Grenada is one of the islands of the Lesser Antilles archipelago in the southeastern Caribbean Sea, once discovered by Christopher Columbus himself. Later, this land was contested for nearly 300 years by several European powers until the British Empire established control at the end of the 18th century. Grenada became part of the Windward Islands colony.

In exchange for the exterminated indigenous peoples, the British brought African slaves — their descendants still make up over 80% of the island’s population. Time passed, and in 1967 Grenadians first gained broad autonomy, and seven years later, de facto independence from London within the British Commonwealth of Nations. From 1967 to 1979, the country was effectively governed by Eric Gairy, Prime Minister from the United Labour Party of Grenada.

The party’s name should not be misleading; Gairy began his career as a trade union activist and defender of the black majority’s rights. Upon gaining power, he quickly transformed into an ultra-right populist and staunch anti-communist, fully oriented towards the U.S. By the late 1970s, Gairy’s regime had become intertwined with local organized crime, institutionalized corruption, and harshly suppressed dissent.

The prime minister apparently grew bored: year after year, he became increasingly fascinated by various esoteric and pseudoscientific ideas. Ironically, this harmless eccentricity ultimately ruined the autocrat. In spring 1979, he flew to New York for a United Nations summit — to persuade world diplomats of the need to seriously study UFOs — which the opposition took advantage of.

On March 13, in the capital St. George’s, power was seized by the pro-communist movement The New JEWEL. The catchy acronym (in English, jewel means “gem”) concealed the dull official name: Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education, and Liberation — a joint campaign for prosperity, education, and liberation.

Gairy unsuccessfully tried to contest the events. Neither the U.S. nor any other power was willing to help the corrupt esoteric return to power. Both regional countries and the world effectively recognized the March 13 coup and the new Grenadian prime minister — the JEWEL leader Maurice Bishop. This charismatic lawyer, famous for defending the poor, was not yet 35 at the time. Energetic Bishop was determined to transform his homeland from a semi-criminal Caribbean backwater into an island of progress and social justice.

The new leader openly expressed his far-left views and sympathies toward the pro-Soviet bloc. Bishop was particularly impressed by geographically close Cuba, with whose authorities he immediately established close ties. Ironically, Grenada legally remained a monarchy under the nominal authority of Queen Elizabeth II. Maurice was loyal to the UK and maintained constructive relations with the former metropolis — despite his coup coinciding with the victory of the very different-in-spirit Margaret Thatcher in London.

Big Ambitions on a Small Island

Bishop did much good for Grenada. He fought organized crime, corruption, illiteracy, and social inequality. The JEWEL government built new factories and developed the dilapidated infrastructure left from Gairy’s time: roads, bridges, power grids, and water supply. Soviet press later claimed that before the October 1983 crisis, Grenada achieved an annual GDP growth of 5-6%.

However, even if true, Bishop’s government was not immune to the classic trap for such regimes. Their sincere desire to transform the country led Grenadian revolutionaries to economically costly projects, expropriation of others’ property, and political repression. And these repressions were widespread: prisons held former Gairy supporters, critics from liberal positions, and overly moderate JEWEL activists. The number of political prisoners in “red” Grenada ran into the hundreds — not many by absolute numbers, but significant for a country of just over 100,000 people.

Another major miscalculation by Bishop was confrontation with the U.S. Although Americans tacitly accepted the March 13, 1979 coup, they decided to punish the Marxists with a quiet economic war. American banks refused loans to St. George’s, tour companies cut trips to the island, and businesses reduced purchases of Grenadian bananas, cocoa, and nutmeg. Maurice responded with public anti-American tirades, which further strengthened U.S. hostility toward him.

Imperialism is frightened by our revolution; it fears losing its profits because the dollar is its only god. It fears the historical example of the Grenadian revolution, which shows what a small, poor country with limited resources can do when its people take their destiny into their own hands.

- from a typical speech by Bishop

Bilateral relations sharply worsened after the June 19, 1980 incident. On that day, an explosion near the platform for honored guests at a JEWEL rally in St. George’s killed three bystanders. Bishop and his comrades were unharmed, but the politician predictably accused U.S. intelligence services of an assassination attempt — without any evidence. It remains unclear who was behind the explosion. Grenadian security forces allegedly identified a suspect but killed him during arrest; the investigation ended there.

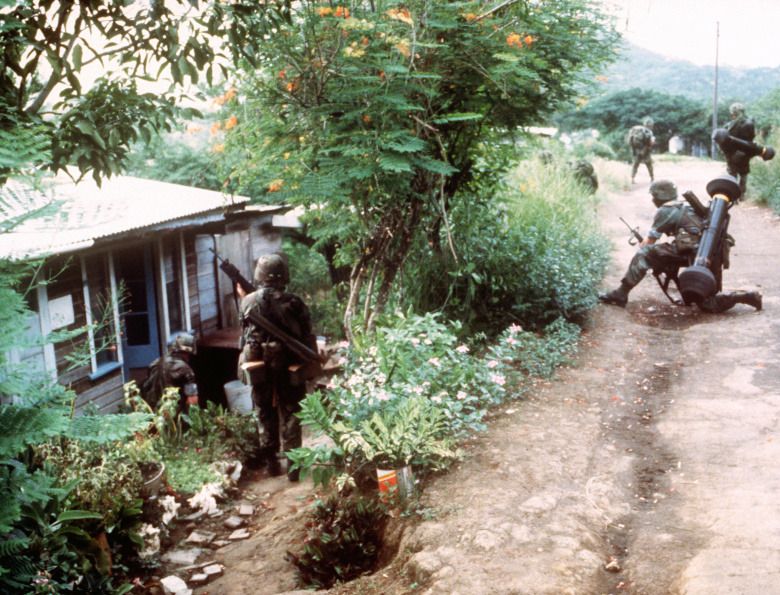

Incidentally, the June 19, 1980 march in Grenada’s capital was not just by ruling party supporters. Bishop held the country’s first-ever military parade — JEWEL loved playing militarism. By 1983, Grenada had a People’s Revolutionary Army of 1,500 soldiers and officers. Their arsenal included about two dozen Soviet BMP infantry fighting vehicles and BRDM armored scout cars, supplied by Cuban comrades. Of course, by Old World standards, this “armada” might have only elicited a smile. But for the tranquil Antilles, where state armies usually consisted of a couple of coast guard companies, Grenada’s PRA looked quite formidable.

This unnerved neighboring former British Windward Islands: Barbados, Dominica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent, and others. Local pro-American elites feared that the full might of Grenada’s PRA was aimed at them, and that soon the revolutionary neighbors would “liberate” their peoples as well. In spring 1982, Bishop escalated the situation with a large new project. Grenadian authorities announced the construction of a modern Point Salines airport — ostensibly a civilian facility for tourist flights. The White House, however, saw Point Salines as a future base for Cuban Air Force, potentially threatening the U.S. Suspicions were fueled by the fact that Cuban construction workers were building the airport.

Right-wing circles in the U.S. began talking about a military operation in Grenada as a matter of national security. Although few could have predicted then that American soldiers and Marines would fight not Bishop, but his killers.

Lady Macbeth of the Caribbean County

In 1983, tensions around Grenada seemed to be easing. Bishop himself began to tire of confrontation with the U.S.: the withdrawal of American business was hitting the island’s economy hard, and no aid from Cuba or the rest of the socialist bloc compensated for the damage. In 1982-1983, the Grenadian leader personally visited the Soviet Union and its leading satellites, from North Korea to the GDR. Nowhere did Maurice find potential sponsors for Caribbean socialism: the “second world” was inexorably engulfed in economic crisis.

Privately, Bishop hinted to comrades that changes were inevitable. They would have to normalize relations with the United States, accept IMF loans, and thus liberalize politics and economics. But such prospects did not suit everyone in JEWEL’s leadership. Some saw this turn as betrayal, others had grown accustomed to unlimited power. An orthodox faction emerged within the party — OREL (Organization for Revolutionary Education and Liberation). The Russian-sounding acronym was no accident — the group sought full Sovietization of Grenada.

Formally, the rebellious bureaucrats were led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard — Bishop’s childhood friend and longtime right-hand man. Everyone knew that behind the weak-willed Coard stood his wife Phyllis, who long envied Bishop and his common-law wife Jacqueline Creft. But vain Mrs. Coard was also a pawn in a larger game. The real mastermind of the conspiracy against the prime minister was an even more sinister figure — General Hudson Austin, commander of the Grenadian army and an open fan of East Asian pro-communist dictatorships.

On October 12, 1983, the OREL faction launched its attack. During a meeting of the ruling party’s Central Committee, Coard and Austin removed Bishop from power and placed him under house arrest. The coup outraged many of Maurice’s supporters. On October 19, an angry crowd freed their idol from custody and decided to celebrate with mass rallies at the old Fort Rupert. Austin quickly reacted and sent PRA units against the demonstrators. Soldiers dispersed the crowd with automatic fire and recaptured Bishop. The politician was immediately executed along with ten loyalists, including Jacqueline Creft. The executioners were not deterred even by the fact that the poor woman was pregnant.

The tragedy at Fort Rupert shattered the moral horizon of Grenadian events. On one hand, the question of power on the island was settled. Hudson declared himself head of the military junta and imposed a 24-hour curfew. On the other hand, the horrific incident shocked the previously peaceful Windward Islands. Barbados Prime Minister Tom Adams told American diplomats he did not want to live next to such a neighbor and would welcome U.S. military intervention.

Adams was joined by other island leaders. On October 21, an extraordinary session of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States concluded that the new authorities in St. George’s might allow the island to be used as a military foothold by Cubans. Following the OECS charter, the assembly proposed Barbados, Jamaica, and the U.S. conduct a peacekeeping mission in Grenada.

Democracies Choose War

It turned out that resolving the Grenada crisis depended entirely on the political will of the White House. The ruling Republicans found themselves caught between the specters of several major U.S. failures during the Cold War.

Above all, Reagan, Bush Sr., and Shultz feared the notorious “Cuba 2.0”: under Austin’s command, Grenada could indeed become another unsinkable Soviet aircraft carrier in the Caribbean. Moreover, hundreds of Americans were on board at the time — and the country was still reeling from the hostage crisis in Islamist Iran. But a military solution also seemed reckless: the Vietnam nightmare was still fresh. After careful consideration, the American leadership chose the risk of military failure over the shame of inaction.

In a mad rush, the military prepared the Urgent Fury plan — an invasion of Grenada involving all branches of the armed forces. The unexpected mission caught both green recruits and seasoned generals and admirals off guard. The invaders simply lacked reliable topographic maps of the island; officers used copies from tourist guides instead. It became clear that even the mighty CIA had only a rough understanding of the situation in Grenada — agents had to interrogate everyone remotely connected to the island.

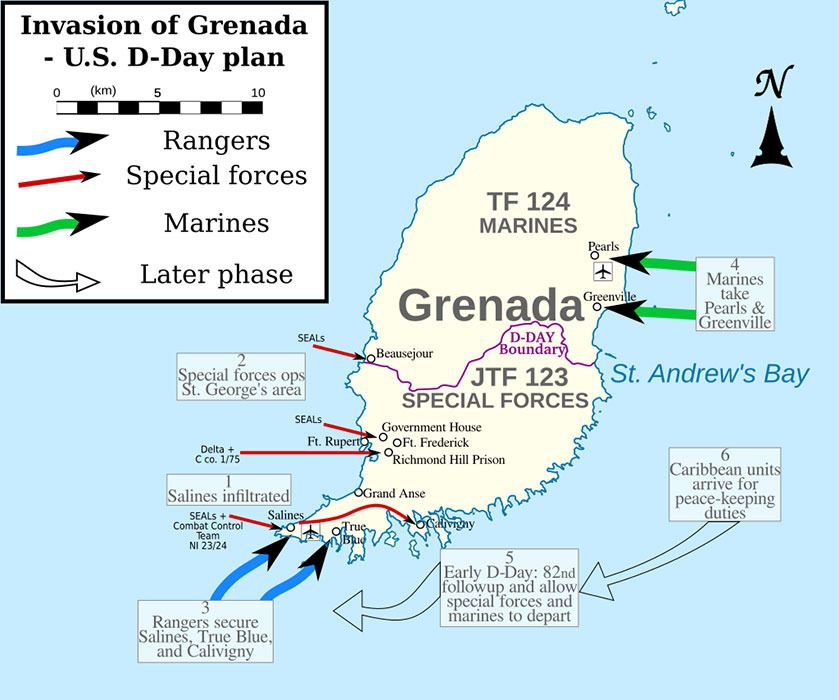

Nevertheless, the U.S. assembled a force of 7,300 troops for Urgent Fury within days, supported by 12 warships, 70 aircraft, and 30 helicopters. Washington placed overall command under Vice Admiral John Metcalf. The ground operation was overseen by General Norman Schwarzkopf. The plan was for the air force to suppress key Grenadian military targets, while infantry from sea and air would take full control of the island.

The president’s decision is driven by two main reasons. First, he is concerned about the welfare of American citizens living in Grenada. […] Second, the president received an urgent message from nearby countries of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, which concluded that events [in Grenada] could seriously affect security and peace in the region.

- George Shultz, 60th U.S. Secretary of State

The operation was symbolically joined by the “five Eastern Caribbean democracies”: Barbados, Dominica, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Together, they contributed 350 troops who did not participate in combat but rather legitimized the actions of their senior ally by their presence — implying the U.S. was not invading Grenada by brute force, but conducting a legitimate operation at the request of the island nations themselves.

Grenada in Three Days

At about 5:30 a.m. on October 25, the Americans began landing on the island. Their intelligence never fully clarified the enemy’s strength, so the landing force faced many unknowns. For example, persistent rumors circulated among the Americans that Grenada was teeming with Cuban military personnel.

As it turned out, there were about 800 Cubans on the Eastern Caribbean island, usually registered as airport construction workers at Point Salines. Almost all were armed, claiming the weapons were for “self-defense.” In the first hours of the invasion, it was the Cubans who fiercely resisted the Americans at Salines. Notably, the defenders used not only Kalashnikov rifles but also Soviet anti-aircraft guns and armored personnel carriers against Rangers from the legendary 75th Ranger Regiment. However, by 10:00 a.m., the invaders had broken the enemy’s resistance. Within hours, Point Salines was receiving American reinforcements.

Meanwhile, other key targets were seized: the old Pearls airport, Fort Rupert, and the residence of British Governor-General Sir Paul Scoon. The official immediately agreed to cooperate with the invaders. In hindsight, Scoon signed a letter prepared in the State Department requesting the U.S. to “assist in the prompt restoration of peace, order, and democratic government in Grenada.”

The island’s main radio station, “Free Grenada,” fell in the first hours of the operation. Instead of government broadcasts, it immediately began transmitting American propaganda. Residents were persuaded over the airwaves that resistance was futile because Austin’s junta had already been captured — which was not a lie, as they were indeed taken prisoner on October 25. By evening, PRA units increasingly avoided combat or surrendered.

However, the hastily planned Urgent Fury did not go entirely smoothly. Cuban instructors had taught their PRA protégés to fire Soviet anti-aircraft machine guns (Bishop did not manage to acquire missile launchers). Because of their fire, the Americans lost nine helicopters over three days, including three brand-new UH-60A “Black Hawks.”

The lack of information about the island also showed. One of the top priorities given to soldiers and Marines by their command was to find fellow countrymen students as soon as possible. It was assumed they were all in the Blue Campus in southern Grenada. However, when the troops fought their way to the dormitory, it turned out there were actually three such campuses. The Blue housed the smallest of the three communities. Finding and evacuating the other Americans required additional time. The students later recalled that they were preparing for midterms that fall; no one followed the news, and Grenadians were notably friendly toward them. Many Americans first heard about Austin’s coup and Bishop’s murder from unexpected guests in military uniform.

The true goal of the Americans was not the rescue of their compatriots. The president and his advisers had a passionate desire to improve the prestige of the United States, especially at home and within the armed forces, where morale had plummeted after Vietnam.

- Mark Edkin, British military expert

Not all incidents related to Urgent Fury were so bizarre. On October 26, an A-7 carrier-based attack aircraft bombed a psychiatric hospital in St. George’s, killing 18 patients. Military pilots later explained the mistake as enemy treachery. Allegedly, soldiers loyal to Austin deliberately moved the national flag from a nearby general staff building to the hospital, and the inexperienced A-7 crew was fooled by the ruse.

Nevertheless, such incidents did not affect the campaign’s outcome. On October 27, PRA soldiers and Cuban “self-defense” forces surrendered en masse, with only isolated units continuing sporadic resistance. On November 1, the last major Grenadian army garrison on the island of Carriacou — 19 men — surrendered to the Americans.

“Hundreds of countries against us, but that doesn’t stop me from having breakfast”

During the three days of fighting, Grenada’s PRA lost 45 soldiers and officers, and their Cuban allies lost between 24 and 27 “builders.” Unfortunately, civilians also suffered — at least 24, including patients killed in the St. George’s psychiatric hospital. Several hundred combatants and civilians were wounded.

The U.S. force suffered 116 wounded and 19 killed. Only ten American soldiers died directly from enemy fire. Five died due to accidents: friendly fire, accidental detonation of shells, and hard landings of downed helicopters. Four Navy SEALs were killed by their own commanding officers. On the night before the landing, despite stormy weather and pitch darkness, the “frogs” were sent ashore on a reconnaissance mission. The entire group perished in Caribbean waters.

The international community predictably condemned the U.S. Grenada campaign. Most governments — especially members of the socialist bloc and “socialist-oriented” countries — considered Urgent Fury an illegal invasion of a sovereign state. But the mountain gave birth to a mouse: U.S. opponents limited themselves to expressions of deep concern in a UN text and a series of anti-American articles in left-wing media. “A hundred countries have disagreed with us before, which doesn’t stop me from having a peaceful breakfast,” Reagan cynically summarized on the matter.

For the White House, there is only one law — the imperial ambitions of the most reactionary forces of American imperialism. President Reagan is intoxicated by them, who in a mad pursuit of world domination elevates international terrorism to the level of official U.S. policy.

- from an article in the Soviet “Izvestia,” October 31, 1983

The White House was only unpleasantly surprised by the position of its number one ally, Great Britain. Margaret Thatcher was genuinely outraged that overseas partners presented her with a fait accompli regarding the Grenada invasion, without any consultations — the fig leaf of the “five Eastern Caribbean democracies” and Governor Scoon’s letter did not convince her. Thus, the Iron Lady took a principled stance: Grenada is a member of the Commonwealth, so introducing foreign troops without London’s consent was outrageous and unlawful. However, Reagan smoothed things over with a personal apology over the phone, after which British-American relations returned to normal.

The Urgent Fury operation was largely aimed not at an external but an internal audience. And this calculation worked: the silent majority of Americans saw the Caribbean campaign as an “anti-Vietnam.” Citizens appreciated how their troops overthrew a communist regime in a geographically close country with minimal losses and literally in three days. Against this backdrop, attempts by several Democratic politicians to condemn Reagan for “gunboat diplomacy” predictably came to nothing. It’s worth recalling that a year later, the 40th U.S. president literally crushed his Democratic opponent in his second election.

We could not allow the ghost of Vietnam to forever hover over the country and prevent us from defending the legitimate interests of national security. […] We didn’t ask anyone’s permission; we acted as we saw fit.

- Ronald Reagan

Gratitude for the Occupation

In retrospect, the American invasion of Grenada looks ideal in terms of both enemy choice and timing. Austin’s junta, which came to power literally over the body of a pregnant woman, was nowhere near a legitimate government. The modest resources of their country gave OREL leaders no chance to fight the opponent on equal terms. Meanwhile, all attempts by the USSR and its allies to accuse Washington of aggression were hypocritical — since the Soviet Union had been fighting in Afghanistan for four years already.

International concern about Grenada quickly subsided. After their military victory, the Americans acted with uncharacteristic restraint in the foreign country. Most troops were immediately redeployed elsewhere, and the remaining contingent (fewer than 3,000 by the end of 1983) simply helped Grenada’s transitional authorities maintain order. It’s important to emphasize: the vast majority of islanders accepted the American occupation as the lesser of two evils. The occupiers encountered neither guerrilla warfare nor sabotage from locals.

At the moment, there is no doubt that the invasion was popular among the population. Overall, the Americans were well received. People smile at them and talk with them.

- from a report by Spanish newspaper Pais, November 1983

On December 3, 1984, parliamentary elections were held in Grenada. The “New National Party” — an alliance of right-wing forces that had once opposed Bishop’s regime — won an overwhelming victory with nearly 60% of the vote. Supporters of the late politician were allowed to participate but were soundly defeated: less than 5% and no seats in the House of Representatives. Clearly, after the bloody autumn of 1983, Grenadians had noticeably sobered and abandoned their former socialist dreams.

Leaders of the ill-fated OREL faction faced justice in their country — charged with usurping power and mass murder. On December 4, 1986, the court sentenced General Austin, the Coards, and fourteen accomplices to long prison terms or death, later commuted to life imprisonment. In the 2000s, judges softened most sentences, and many of the aging “eagles” were released. Widowed Bernard Coard still lives a private life in Jamaica.

In the United States, the Urgent Fury operation gradually faded from memory — after all, it lacked the intensity, drama, and casualties of Iraq or Afghanistan. But in Grenada itself, the events of 1983 are well remembered, and no resentment toward the powerful continental neighbors persists. October 25 remains a national holiday, Thanksgiving Day — commemorating the restoration of democratic order in the country.

Main sources of the article:

- Brands H. “Decisions on American Intervention: Lebanon, the Dominican Republic, Grenada”;

- Dotsenko Yu. “Fleets in Local Conflicts of the Second Half of the 20th Century”;

- Egupets A. “How the USA Occupied Grenada 40 Years Ago“

- Kintzer S. “The Days of Our Weakness Are Over: Grenada”;

- Ponar Marchuk E. “Grenada-1983: Fallen Americans”;

- Roblin S. “Possible Reasons for the U.S. Invasion of Grenada”;

- Testov O. “Grenada: Revolution and Counterrevolution”;

- Edkin M. “Urgent Fury: The Battle for Grenada. The Truth about the Largest American Campaign since Vietnam”