Support the author!

How America Became One of the Most Hostile Countries for Immigration and Political Asylum

Since early 2022, thousands of opponents of the Russian invasion of Ukraine have tried to seek asylum in the US — only to face tightening immigration policies. With Donald Trump’s return to the presidency, those who hadn’t secured legal status in previous years found themselves in direct danger. Since early 2025, US authorities have deported two activists to Russia — Vladimir Mashinin and Leonid Melekhin. The first managed to escape; the second was placed in pre-trial detention last week for two months due to anti-war statements made in previous years. Julia Nikolaeva, a US immigration lawyer of Russian origin practicing in San Francisco for 15 years, confirms that the situation for asylum seekers in the States has significantly worsened, as has the overall attitude of authorities toward foreigners. We spoke with her about this.

- Recently, Russian anti-war activist Leonid Melekhin was deported from an American immigration detention center to Russia, where the court placed him in pre-trial detention. A similar case happened in January this year with activist Vladimir Mashinin. Does this development threaten other anti-war Russian emigrants awaiting political asylum in the US? And how many Russian citizens are at risk?

- We don’t have exact statistics because neither the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) nor Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) publishes official numbers on how many Russians are held in detention centers (immigration jails). We also don’t know the overall statistics for approved or denied asylum applications filed by Russians. Such data likely exists within the system but isn’t officially released. For some time, I tried to gather these figures empirically by checking the number of Russians in each detention center, but that proved impossible — there are over 200 centers in the US. Moreover, detainees are constantly rotated; ICE transfers people between centers. Currently, more than 56,000 migrants are held in immigration detention, but we don’t know how many of them are Russian.

In practice, we see immigration prosecutors filing appeals on all cases won by Russians. This means a judge’s ruling in favor does not become legally effective for the next 30 days. If the prosecution doesn’t appeal within that period, the court’s decision takes effect and the person is released. If an appeal is filed, the process drags on for several more months. A year ago, appeals in cases involving detainees took three to four months; now it can take seven to eight months, during which the person who won the case remains in immigration detention. The same applies if someone loses a case and appeals — they stay in jail during the appeal. If the appeal is lost, the deportation order becomes final and the person is deported.

Since there are no direct flights between the US and Russia, Russians are deported through third countries — Turkey, Qatar, China — and many try to escape during layovers. By procedure, deportation officers escort deportees until boarding the final flight directly to Russia. Their documents are handed to the flight crew, and in Russia, FSB agents meet the deportees. For many, this can mean arrest and real prison time, so people try every way to convince escorts to give back their documents and let them go during layovers, and sometimes they succeed. But not everyone is so lucky.

So far, I don’t know of any case where someone was arrested at a Russian airport during the deportation process from the US. I get the impression there’s an informal understanding between Russian and US authorities not to arrest Russian opposition figures deported from the US immediately, as this could cause a broad public outcry and call into question the legitimacy and fairness of American court decisions. In most cases, judges deny asylum, reasoning that they don’t see real danger even for political activists who have had trouble in Russia, and immediate arrests upon return would seriously undermine this position.

- But that’s exactly what happened with Leonid Melekhin — he has been in pre-trial detention since July 25.

- No, he was not arrested at the moment of deportation from the US but some time later. The judge denied him asylum, stating there was insufficient basis to fear persecution in Russia. This particular judge, Christine Perry, often refers in her decisions to the fact that the person is not a well-known or public figure and therefore unlikely to attract government attention.

- Did he have the chance to flee Russia?

- Yes, many do so, but for some reason he didn’t consider it necessary to leave. The Russian police, FSB, and Center E operate rather chaotically, so some hope their case will be overlooked — especially if some time has passed and they believe they’ve been forgotten. Perhaps Leonid thought so when he wasn’t arrested immediately upon his return. Many think this way. While for influencers and opinion leaders the danger is obvious and almost certain, for ordinary people persecution is fairly random.

- Do you know why Leonid didn’t file an appeal?

- No. I saw his case materials, but he wasn’t my client; he had another lawyer, so I can’t discuss the details. Many refuse to appeal because the chances of winning are very low, but an appeal prolongs detention by several months.

I observe courts tightening their standards for “well-founded fear of future persecution.” An asylum seeker must prove either past persecution for certain reasons or a well-founded fear of persecution if returned to Russia. Established precedent requires showing at least a 10% chance of persecution. Now many judges take the position that without concrete evidence of a criminal case, a wanted notice, or summons as a suspect or accused, the risk of persecution isn’t proven. This is legally incorrect because it far exceeds the required standard — we need to prove 10%, but they demand proof of nearly 100% likelihood.

I know well the judge who deported Leonid Melekhin because I’ve worked with her multiple times in the Calexico detention center on the Mexican border. She doesn’t seem harsh or aggressive during hearings, but her stance is: if you’re not a well-known person, you have no risks. She likes to ask how many social media followers someone has. When we cite examples of arrests of ordinary people who never engaged in politics but wrote a few comments, or the case of pediatrician Nadezhda Buyanova, who had no political activism and simply spoke carelessly at a clinic and was sentenced to 5.5 years due to a patient’s mother’s denunciation — none of this convinces judges. They want ironclad proof that you personally are awaited and wanted for arrest.

- Can we estimate how many Russians have gone through deportation procedures from the US in recent years but never made it back to Russia?

- I know for sure it’s already dozens, probably even hundreds. This didn’t start under Trump but during Biden’s term. Back then it was less widespread; now such cases have noticeably increased. The influx of Russians seeking political asylum in the US grew significantly after the full-scale war in Ukraine began, and many completed the process and lost appeals roughly around 2024-2025. Hence, the number of Russian deportations has increased substantially.

- But that’s hundreds, not thousands. Latin Americans make up a huge share of detainees — their numbers far exceed Russians.

- In the overall flow, Russians probably make up less than 5%. Their numbers have increased sharply compared to previous years, but it’s hard to surpass Latin America, Africa, China, and India.

- You previously mentioned an ICE directive regarding citizens of Russia and other former USSR countries that immigration officers refer to — does it still exist? What does it entail?

- It’s no longer relevant. The directive definitely existed from spring last year; I saw a screenshot. Although not officially published, its existence was confirmed by ICE officers, prosecutors in court, and judges who knew about it. Its essence was that Russians and citizens of several other post-Soviet countries entering via Mexico under the CBP One program must be held in detention until their asylum hearings conclude. Previously, people entering under CBP One were released and went through the process while free. Detention was usually for men with legal troubles or suspicions, but the majority proceeded free. Women and girls were never detained except those with criminal issues. In April-May 2024, authorities began detaining all citizens of certain countries, men and women. I noticed this, investigated, and learned about the directive for citizens of specific countries. This was under Biden. Under Trump, this practice expanded to migrants from any countries. So it’s no longer accurate to talk about discrimination specifically against Russians.

The problem is elsewhere: by law, ICE has virtually unlimited authority over those in deportation proceedings. It’s important to understand that even people who entered legally under CBP One and sought asylum are placed in deportation proceedings until a court decides on their asylum claim. If granted, the person receives legal status. If denied, they are deported. ICE decides who stays free and who goes to detention for the entire process.

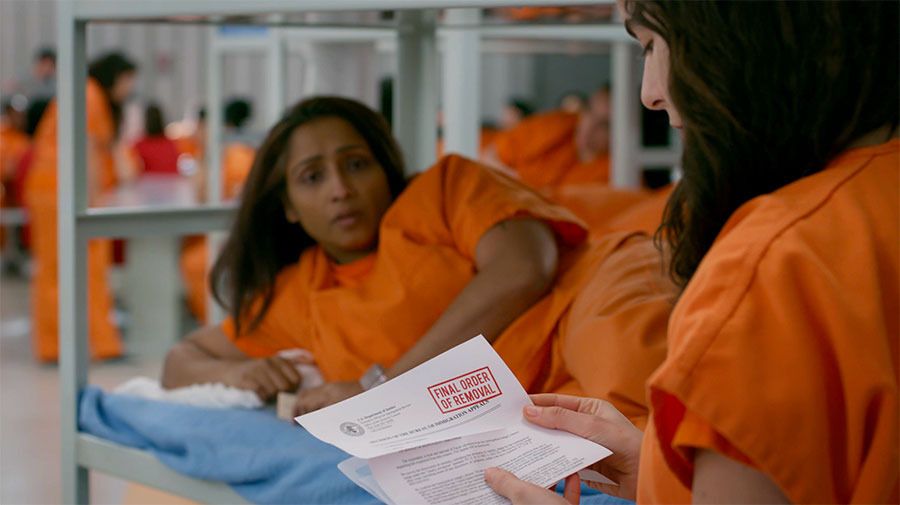

- You mentioned Russian women detained by ICE — I immediately thought of Orange Is The New Black, the Netflix documentary-style series about life in American women’s prisons. The last season, released in 2019 during Trump’s first term, focuses on detention centers where migrant women end up. The creators portrayed these as the worst prisons in the US, where human rights are fundamentally ignored. The June riot in Los Angeles during ICE immigration raids confirmed this: people are ready to take to the barricades to avoid detention. Why did ICE become such a feared enforcement agency in America?

- It’s definitely Trump administration policy. Since combating illegal immigration was a key campaign promise, Trump set a very tough tone implemented by his appointees at all levels. Thus, among law enforcement, ICE became the most powerful. Under Biden, for example, ICE was prohibited from making arrests in certain places called sensitive or protected areas — churches, schools, hospitals. This had a humanitarian purpose because the US is a democratic, developed country that cannot allow people, even undocumented immigrants, to lose access to education or healthcare. Now people fear sending their children to school, going to hospitals, or attending church because all these protections were removed under Trump.

Now ICE can act anywhere, anytime, without restrictions. Many Americans don’t realize this will affect them too. Recently, in Southern California, ICE raided a cannabis farm and detained a US citizen, holding him in solitary confinement in a federal prison for three days — despite his immediate declaration of citizenship and their ability to verify it. He served in the US military and spoke without an accent. The only reason for detention was his Latino appearance. Such cases will become more frequent among people here legally.

Why did the Los Angeles riot happen? Because ICE officers behaved so brazenly and disrespectfully that many Americans saw it as a militaristic intimidation. They’re not used to armed, masked, fully equipped officers storming their communities and homes. That’s what sparked the outrage.

- Who makes decisions on ICE cases — special immigration judges or general jurisdiction courts?

- There’s an important nuance. These are not federal or general jurisdiction courts where judges have lifetime appointments, procedural independence, and decide cases as they see fit. Immigration judges are appointed by the Attorney General and are administrative judges with different authority. They are easily appointed and dismissed — which Trump’s appointed Attorney General Bondi is currently doing. Several dozen immigration judges, mostly appointed during Biden’s term, have been fired without warning: a judge arrives at work and finds their electronic key doesn’t work, no longer has access to the courthouse — they were fired that day. Immigration judges don’t feel fully independent and show varying degrees of loyalty to new policies. Many principled judges resigned rather than wait to be fired when they saw where things were headed.

As a result, the immigration judiciary has changed dramatically.

Sometimes I come to court and don’t feel like I’m facing a judge: I’m facing two prosecutors. Last week I had a hearing in Arizona, in Eloy prison, with a judge who denies asylum in over 90% of cases. That means you’re not dealing with a judge.

Although I came with one of my strongest cases, I knew this judge wouldn’t grant asylum even in such a convincing case. My client belonged to the LGBT community, which is recognized as an extremist organization in Russia — many judges previously granted asylum on this basis. We also had evidence that a criminal case was opened against her for discrediting the army, summons as a suspect, witness testimony confirming she was wanted — it’s hard to imagine a stronger case. Yet the judge said: since discrediting the army in Russia carries punishment from a fine to five years, let’s hope she only gets a fine! Of course, we’re appealing because cases like this must not be lost. This is literally a matter of life and death — if this woman is deported to Russia, her likelihood of arrest is 100%. Is this a judge if he considers deporting someone in such a situation acceptable?

- Such a high conviction rate is typical for the Russian justice system. Now in America too?

- Yes, it’s a fair comparison statistically regarding judge decisions. I rarely encountered judges with over 90% denial rates before; now it happens more often. Of course, there’s a big difference between democratic and Republican states — in Georgia, Texas, Louisiana, judges are always much tougher. Although the federal law is the same, its application varies widely.

- How much can American civil society influence the situation? The Los Angeles riots showed that not only migrants are concerned.

- Honestly, I don’t see an organized, thoughtful, consolidated response from Democrats or a coherent political action plan. Immigration is a highly politicized topic; much of Trump’s campaign promises were built on ending illegal immigration. The breakdown happened when he equated immigrants with illegals, and illegals with criminals in public perception. When Trump talks about 14 million illegal immigrants, he doesn’t specify that several million entered legally, followed rules, filed documents, but due to system backlog and years-long waits, they remain in limbo without legal status. These are fully legal immigrants, but Trump lumped them with illegals and equated illegals with criminals. Many believed this distorted narrative.

The strong outrage in Los Angeles arose because it traditionally has a huge immigrant population, and Americans living alongside them see they are normal, law-abiding, working people — not scary criminals dealing drugs and weapons. When families are torn apart, imprisoned, deported, many are outraged simply on human grounds — decent people dislike such unjustified cruelty. Even if immigration laws are violated, it shouldn’t lead to inhumane, brutal police methods. Besides moral issues, there’s a legal side — ICE commits many legal violations.

- Do you think the Los Angeles unrest affected ICE leadership at all?

- Definitely not. I don’t see any change in their methods. Maybe ICE will act more cautiously where local communities are strongly intertwined with immigrants. But overall, I don’t see them changing direction or reducing raid intensity.

I still hear about raids and arrests and about them seeking new targets. Earlier, raids focused on places where Latin Americans gathered for cash work — repairs, loading, transport. Then raids targeted farms where many migrants work. Then factories and hotels. Now, in Sacramento, where many Russian-speaking immigrants live, ICE conducts raids in shopping center parking lots. People are afraid to just go to the store.

- So if you walk past an ICE officer on the street and speak any language other than English — that’s a risk?

- Yes, it’s a risk. If they realize you’re a foreigner, there’s a 100% chance they’ll approach and ask for documents.

- So, does that mean Russian activists shouldn’t come to America?

- I advise everyone contacting me from outside the US who’s considering not entering with a visa but crossing the border to seek asylum: this is one of the most hostile countries for immigration, especially political asylum. Absolutely.

- What if they have a visa?

- A visa changes things; it allows legal entry. Work immigration still exists. But restrictions are tightening across the board. For example, when a person arrives on a work visa, there are legal pathways to get a green card through an employer. In recent years, this process has stretched to at least five or six years. Authorities now try to complicate and delay this process to discourage employers from sponsoring work green cards. The same applies to family immigration. They introduce many additional checks, interviews, and the process drags on. This increases the number of people stuck waiting for documents without legal status. Actions by authorities don’t match their stated goals.

- I understand you can’t reveal countries through which deported Russians managed to escape. But can you say which countries definitely won’t work?

- It’s very individual. There’s no guaranteed escape route. At transfer points, deportees are usually kept in separate rooms, not in the general transit area, so they can’t just walk away. They have no documents on hand; documents are with the deportation officer who hands them directly to the crew of the last flight to Russia. Only the human factor offers hope.

When ICE transfers immigration detainees within the US, for example from one detention center to another, people are shackled — chains on legs, waist, and hands, dressed in prison uniforms, escorted like dangerous criminals. For example, transfer from California’s Otay Mesa prison to Louisiana, where many Russian-speaking women were sent, took over 30 hours — all while shackled. Deportation conditions are less harsh — deportees usually fly commercial flights accompanied by deportation officers. Much depends on the escort. Some are sympathetic and let people escape at transfer points; others are unyielding.

In any case, it’s important to understand this treatment is not for criminals but for people seeking protection in the US. Even if the court found insufficient grounds to grant asylum, such inhumane methods are wild, unjustified, and unworthy of a country that considers itself civilized.

To draw US authorities’ attention to the problems of Russian political immigrants at risk of deportation to Russia, Most Media is launching a petition. Sign it and help spread the word!