Support the author!

Horizon of Erik Bulatov

In Paris, they said farewell to Erik Bulatov (1933-2025) — a brilliant artist whose works became the most recognizable symbol of Moscow conceptualism of the 1960s-1970s. He himself remained one of the leading figures of contemporary Russian art until his last days, even gaining the status of a classic and living abroad for more than 30 of his 92 years.

Erik Bulatov’s paintings, drawing from the classical painting tradition, speak to us with slogans, poems, symbols, as if confirming their belonging to the art of socialist realism, which the artist nevertheless repudiated. Explaining that his work “…is actually something entirely different from pop art and socialist art. They [artists working in pop and socialist art] tried to prove that social reality is the only thing we have, the only reality. Everything else simply doesn’t matter. But I always wanted to prove that social space is limited, it has boundaries, and freedom is always beyond that line.“

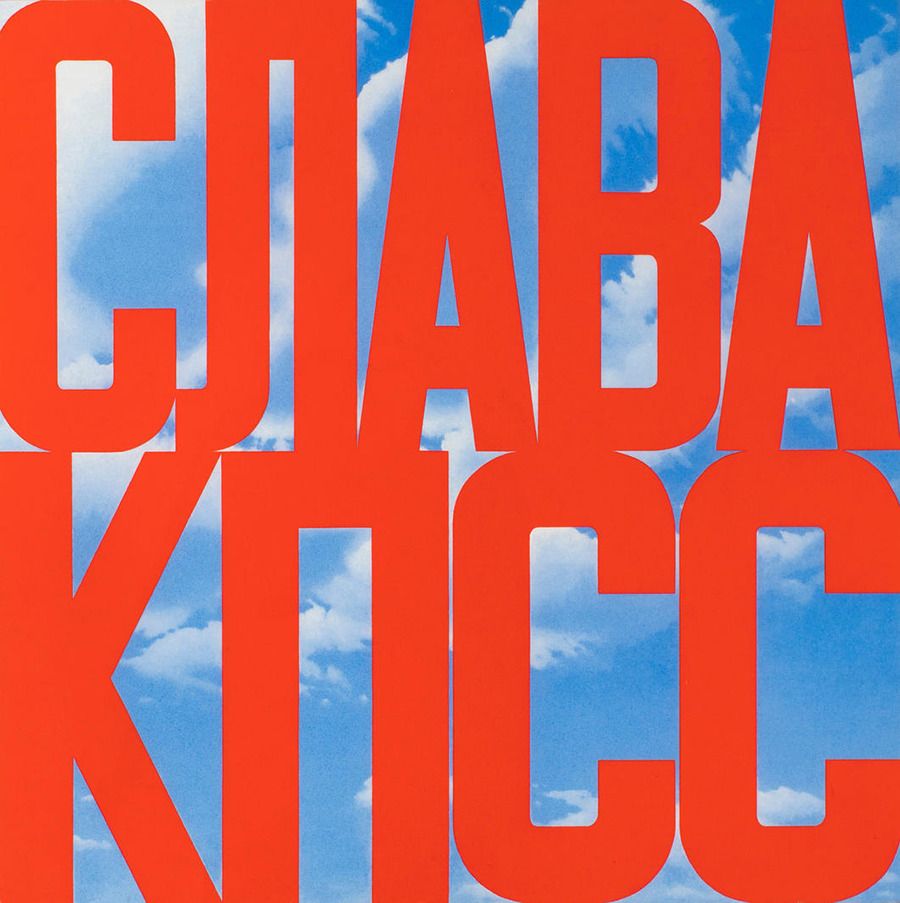

Freedom and the light illuminating the path to freedom are central to Bulatov’s work. Freedom as meaning and goal, a window into a free world, as in one of his most famous works “Glory to the CPSU,” where bold red letters, brought into the title, seem to fill the entire window space. But it only seems so, because the sky in the background, despite the painting’s date — 1975, a hopeless stagnation — inspires hope, air penetrates through the gaps between letters, lifting the stale slogan off the surface.

“Freedom is Freedom is Freedom is Freedom is Freedom is Freedom is Freedom is Freedom is freedom” (2001) reproduces on canvas without cuts a poem by Vsevolod Nekrasov, Bulatov’s favorite poet. Written in white poster font on red, the text occupies the entire square canvas, seemingly torn in the center. And into this hole, inflating the hanging rags, the very freedom about which the artist recently said in an interview that for him it “was the original goal.”

Freedom was the goal for Bulatov and his comrades in the underground scene of those years, which formed an extraordinary artistic environment. Emerging during the Thaw, it did not dissipate at its end or later. One of the centers of this underground was Chistye Prudy and its surroundings. There were studios of Ilya Kabakov and Yulo Sooster, Viktor Pivovarov, Eduard Steinberg, Vladimir Yankilevsky — and Erik Bulatov with his friend Oleg Vasiliev. The geographical proximity led Czech art historian Indrzhikh Chalupetsky to call this group the “Sretensky Boulevard Group,” which, of course, never existed. But there was a fellowship of like-minded people who saw each other’s works and tried to create art free from ideological constraints.

Looking at the hole in the sky in Bulatov’s work, one cannot help but recall the hole punched in the ceiling by the “Man Who Flew into the Sky from His Room,” in Kabakov’s first total installation, which was always assembled for exhibitions and then dismantled because it occupied the entire studio. This was in 1985 — all of them had only a few years left to work in their Moscow studios. Kabakov stayed in New York in 1988, and Bulatov, who arrived there a year later, moved to Paris in 1992, gained worldwide fame, saw his works on the walls of the Pompidou Center, Cologne’s Ludwig Museum, Vienna’s Albertina, New York’s MoMA — and today there are more of Erik Bulatov’s paintings in the West than in Russia. But until the end of his days, he considered himself a Russian artist — without commenting on the changes happening in recent decades, especially in recent years at home. Neither denouncing nor horrified, he readily accepted an invitation to hold an exhibition dedicated to his 90th birthday in 2023 in Nizhny Novgorod. Only, comparing the moment he entered the art world with the current moment, he said that still “…now is a completely different time. There are problems, but different ones. Back then there were orders, the bosses commanded what was allowed and what wasn’t, they let you live, and for that, thank you. I hope today it’s not like that. Although I see that they keep pulling Russia back to Soviet times…”

Where does this thirst for freedom come from? One would like to say it stems from the spirit of the times. But roots certainly played their role. Erik Bulatov willingly spoke about his father, Vladimir Borisovich, born in 1901, a loyal communist and propagandist, who volunteered for the front and died in 1944. Bulatov recalled how his father read him Blok and Balmont, how, seeing little Erik’s drawings for “Ruslan and Lyudmila,” he determined his future profession, how he last saw his father during a short vacation before his death. He was 11 years old. After that, he was raised by his mother alone, who took his father’s wish as a legacy: at 12, Erik learned about the Moscow Special Art School, and upon entering, met his future friends and comrades.

His mother, Raisa Pavlovna Schwartz, born in 1907 in Poland, at 15, seized by the idea of world revolution, illegally crossed the USSR border on her second attempt without knowing Russian, speaking only Yiddish and Polish. She was an incredible woman — just three years later she mastered the language enough to work as a stenographer. Before the war — at the USSR People’s Commissariat of Communications, after — at the Moscow Collegium of Defenders, later renamed the Collegium of Advocates.

Being artistic by nature, she adored theater and found the future son’s name in the Moscow Art Theatre play “Erik XIV,” based on Strindberg’s tragedy, where Erik was played by Mikhail Chekhov, who had not yet emigrated. The first 15 years of life, spent outside dictatorship, did not go to waste.

“[My mother] was against the party’s general line, against any authority, a typical intellectual consciousness,” Bulatov said. “She should have been against my father too, their views were often opposite, but they loved each other very much.”

To add to this, in recent years Raisa Pavlovna retyped samizdat and tamizdat — Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, “Doctor Zhivago.” So it’s clear where her son’s life and worldview got their shape from.

Life in a Fairy Tale

The point is that when talking about freedom, Erik Bulatov primarily meant freedom of creativity, since he never got involved in political battles — he did not participate in apartment, illegal exhibitions, and was concerned that since the 1970s, when the works of domestic nonconformists got to the West through unofficial channels, this art was viewed, according to the artist, “exclusively from a political or historical perspective, ignoring aesthetic principles and the entire global cultural process.“ The remark, quoted by Forbes, mainly concerns the unscheduled Venice Biennale “New Soviet Art. Unofficial Perspective” — the so-called “Dissidents’ Biennale,” organized in 1977 by the president of the Venice Biennale Carlo Ripa di Meana, eager to reform the oldest contemporary art exhibition, with the participation of the famous collector Alberto Sandretti. Bulatov took part in the Venice exhibition not by his own will — on black-and-white film containing photos of nonconformist works that fell into the hands of the exhibition organizers was Bulatov’s “Horizon,” painted in 1971-1972. It made it onto the poster.

This is one of the most famous “talking” Bulatov project-paintings. A pastoral landscape — sea, sky, sand — clashes with a harsh barrier, not from a poster but taken from a government institution. Either the red carpet from a Kremlin corridor or an order ribbon (red with gold — the St. George ribbon was not yet in fashion) separates the sea from the sky on the canvas, and a group of comrades, stepping onto the beach in official attire, completes the impression of state interference in private life. And this is exactly what Bulatov resisted, but — exclusively through the means of art.

Neither he and Oleg Vasiliev nor Ilya Kabakov — all three acquainted since childhood during their studies — participated in unofficial exhibitions because they were formally official artists — illustrating children’s books for Detgiz and the Malish publishing house, where Kabakov brought Bulatov and Vasiliev. Unlike the latter two, who studied graphic arts, Bulatov was originally a painter, moreover, highly regarded at the institute, a Lenin scholarship holder. But after graduating, he rejected the canons of socialist realism forever.

“I did illustrations because I realized I had to be independent,” Bulatov recalled. “The state paid for orders and supported the Union of Artists. I had to be free, earn money by something else. What else could I do? I didn’t know anything else, only how to draw. It was interesting to draw illustrations. Oleg Vasiliev and I did it together and at the same time continued working on our own pieces. Illustrating children’s books didn’t take all the time: six months were tied to books, and the other six months we were free.”

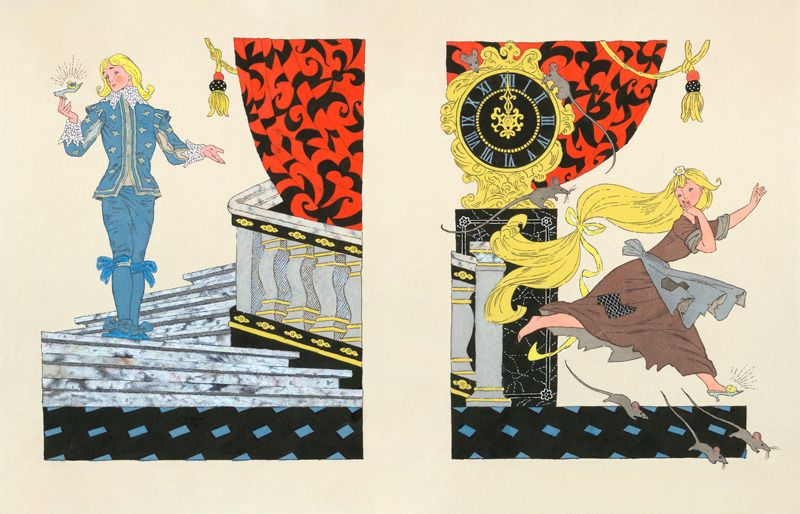

It’s a pity not to recall that Bulatov and Vasiliev condescendingly called those illustrations not art but artistic products, and even in this they sinned against the truth: it’s enough to remember their black Puss in Boots in a red cloak from the cover or Cinderella’s golden hair distracting the eye from the patches on her dress, and tears of tenderness will well up in our eyes, reviving the forgotten childhood sense of magic.

It should be said that children’s illustrations paid well at that time, allowing not to worry too much about other earnings.

But what was common in Bulatov’s fairy-tale pictures and his complexly constructed large paintings was the inner space into which the viewer/reader was automatically drawn, becoming a participant in the events.

Two “F”s

“A picture-object has an edge (or frame), a surface on which paint can be applied; this is, so to speak, the material part of the picture,” Erik Bulatov quoted the great graphic artist Vladimir Favorsky, whom he met after finishing the institute and later considered his teacher. “But at the same time, the picture is a space. Like any quadrilateral of limited surface, it has a center, periphery, edge, each possessing different — in character and quantity — energy; it already has its own horizon and two diagonals, that is, all the spatial elements of the picture. It not only potentially contains spatial possibilities, it disposes of its internal space. The surface separates it from the outside world, and at the same time through the surface it communicates with that same outside world.”

Without delving into Favorsky’s “Theory of Composition,” which managed to describe and justify the relationship of object and space in a painting, we acknowledge that his informal student fully absorbed the lessons.

Bulatov and Vasiliev went to Favorsky, understanding that they did not intend to continue what they were taught at Surikov, and had no idea what real great art was. “We knew there were living priests of this sacred art. They were the three Fs — Falk, Favorsky, and Fonvizin. And we went to them and asked questions. We simply had nowhere else to go. There was no time for pride or politeness, and we were not afraid to look like fools; the question was, in essence, about life.”

They remembered two of this trio throughout their lives; Oleg Vasiliev’s ended earlier — he died in New York in 2013. The second teacher was Robert Falk.

Seeing Robert Rafailovich in 1957 at open showings in Falk’s studio on Prechistenskaya Embankment, Bulatov dared to show the master his works and was not afraid to hear a response. Falk was a hero of the Paris School and at the same time the only living link to the Russian avant-garde, about which Bulatov’s generation knew even less than about contemporary Western art at the time. But Falk’s very existence as an artist, who returned inconveniently in 1937 to his homeland, his quiet life, and his fantastic, despite health and family tragedies, productivity proved that true, fully independent art is possible. In any state, even such as this.