Support the author!

Dunkirk 1940: The Nonexistent Deal. Is It True That Hitler Intentionally Let Hundreds of Thousands of Enemy Soldiers Escape in France?

“The Event That Changed the World” — under this straightforward slogan, Christopher Nolan’s “Dunkirk” was released in 2017. The film is dedicated not to the most hyped event of World War II in mass culture but to the evacuation of Allied troops from the French town of the same name on the English Channel coast, also known as Operation Dynamo. Amid the triumphant French campaign for the Third Reich, the Allies achieved the incredible — they evacuated hundreds of thousands of their encircled soldiers from the continent to Britain, enabling the kingdom to continue the war. Against the backdrop of successful blitzkriegs, such a Nazi oversight seemed unbelievable.

After the war, many historians — Sebastian Haffner, Basil Liddell-Hart, William Shirer — suggested that in May 1940, Adolf Hitler might have deliberately issued a “stop order” to his troops and allowed the British to sail home for his own reasons. In the 21st century, this theory is often regarded almost as a confirmed fact. It is claimed that the Führer supposedly counted on public opinion in the United Kingdom: that the English would see him as a peacemaker and agree to an honorable peace. But the calculation backfired — the final outcome of World War II and Hitler’s fate are known to everyone. But was the dictator really undone by a sudden fit of mercy?

Hamelen, Who Didn’t Catch Mice

First of all, it is worth understanding why at the end of May 1940 the Allies in northern France faced a grim choice — surrender, death, or flight? A superficial glance finds no mysteries here.

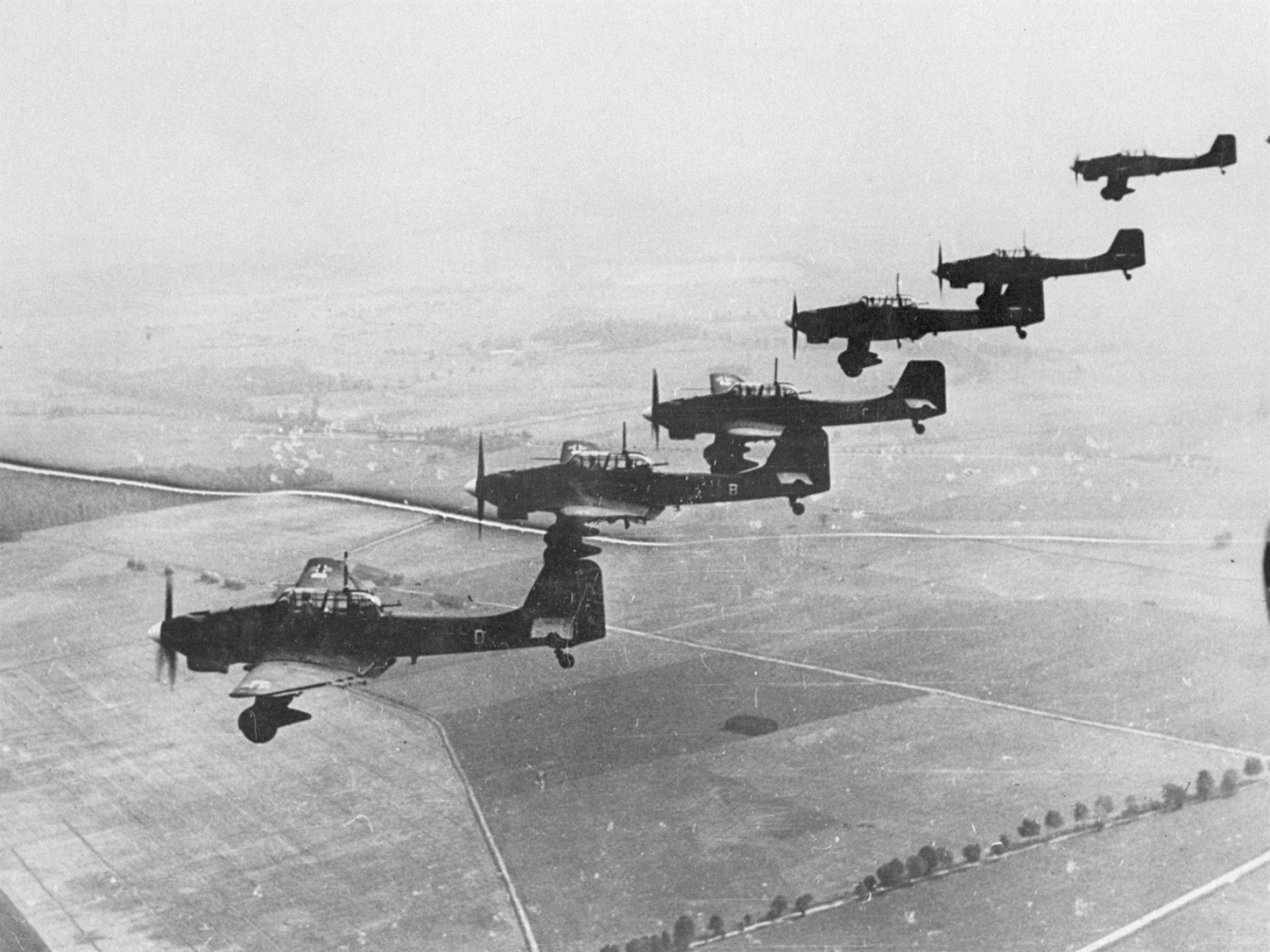

On one side, we see the well-trained columns of the Wehrmacht: a perfect blitzkrieg machine with unstoppable “panzers,” ruthless Ju-87 “Stukas,” and other products of the shadowy German genius. On the other side are the caught-off-guard British, French, and allied troops, unprepared in every sense for a major war. It seems their clash in spring-summer 1940 could have ended no other way.

However, reality is much more complicated than established notions. There are different assessments of the balance of forces between the Wehrmacht and its opponents (the armies of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the British Expeditionary Force), but nowhere do authors grant the Germans an unconditional advantage either in manpower or in equipment numbers. Nor can it be said that Germany possessed some kind of miracle weapon.

For example, the French S-35 tank outperformed the German Pz-III and IV in all key parameters. But the Third Republic, as Charles de Gaulle later recalled, assigned crews of barely retrained cavalrymen who were not always provided with such “details” as radio communication or armor-piercing shells. Therefore, it is unsurprising that the battlefields usually remained in German, not French, hands. In short, the Reich outmatched its victims not in resources but in the ability to use them.

France’s effectiveness was especially poor, despite its special role in the first anti-Hitler coalition. Its army vastly exceeded the forces of its partners, and the key battles of the campaign inevitably took place on French soil. The country declared mobilization and shifted its economy to a war footing but failed to find leaders capable of leading its citizens and allies into battle. Prime Minister Paul Reynaud was a stereotypical politician, capable of fine words but powerless to implement them. The commander-in-chief of the fighting army, Maurice Gamelin, embodied the saying about generals preparing for past wars.

Gamelin’s entire strategy was based on the confidence that World War II would be a remake of the First World War he knew well. The general expected the Germans to try to invade his country through Belgium as they did 26 years earlier. Therefore, the main forces of the army had to guard the northernmost part of the country and be ready to assist neighbors. Until then, the French were to rely on the fortress of the well-known Maginot Line — a fortification complex along the Franco-German border named after the late Minister of Defense.

“The Maginot Line is one of the greatest illusions in history […]. The French believed that a line of fortifications built according to the principles of modern engineering, with personnel sheltered deep underground and guns covering all approaches, could block the enemy’s path for quite a long time.”

- David Devine, British historian

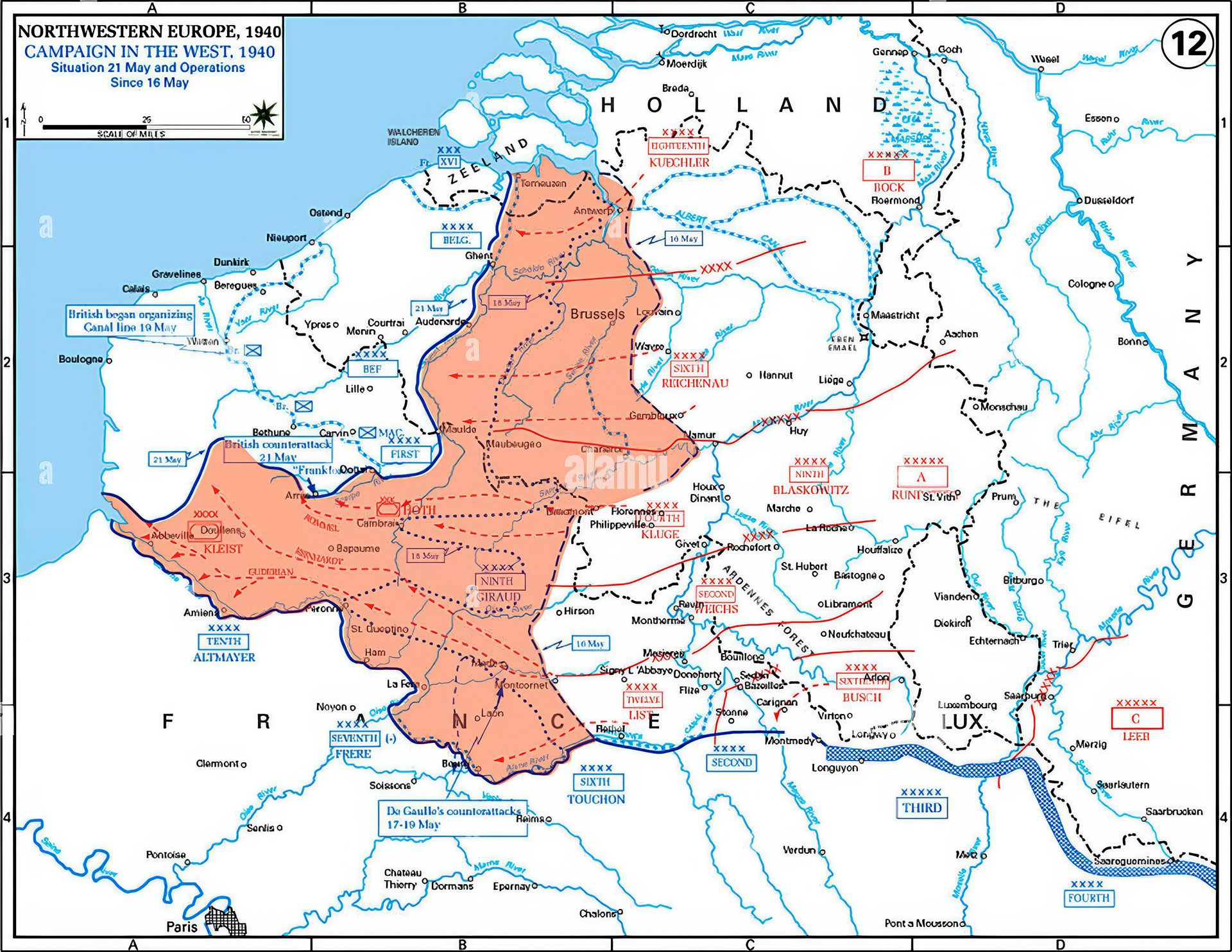

However, on May 10, 1940, the Nazis acted somewhat differently. After eight months of the Drôle de guerre, they launched Plan Gelb (“Yellow”) devised by the main blitzkrieg ideologist, General Erich von Manstein. The auxiliary Army Group B advanced from the north, while the main Army Group A suddenly struck from the southeast — through the Ardennes, a hilly region at the borders of France, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

Gamelin and his officers had overestimated the Ardennes terrain and considered an advance through it impossible. The coalition’s situation quickly became desperate.

Collapsed Front and Divided Allies

On May 13, the Germans — specifically the 7th Division of the legendary Erwin Rommel — crossed the key water barrier in the combat zone, the Meuse River. Other Wehrmacht units soon followed, linking up near Sedan. Allied troops retreated in disarray in various directions.

In northern France, an “enclave” formed consisting of the French 1st Army, the British Corps, and remnants of Belgian forces — increasingly isolated from the main front line. On May 14, the number of allies decreased by one when the Dutch army surrendered. On May 16, newly appointed British Prime Minister Winston Churchill hurried to Paris, where he was quickly advised to abandon all hope.

“Then I asked: ‘Where is the strategic reserve?’ and, switching to French, repeated: ‘Où est la masse de manoeuvre?’ General Gamelin turned to me, shook his head, shrugged, and replied: ‘Aucune’ [‘There is none’].”

- Winston Churchill

On May 19, General Maxime Weygand took command of the French army. The replacement seemed to offer hope of resisting the Germans — the new commander was generally considered more competent than his predecessor. But, first, by that time the strategic situation for the coalition was deteriorating exponentially (by May 20, the Germans had already reached the English Channel near Amiens). Second, Weygand’s political views — ultra-right anti-republican and virulent anti-Semite — caused concern.

Initially, the general tried to turn the tide. Weygand aimed to stabilize the front along the Somme River and hoped the encircled northern troops could break through to their own lines. On May 21-22, the French and British actually counterattacked near the northern town of Arras and even pushed back Rommel’s 7th Division mentioned earlier.

However, the tactical success did not translate into strategic victory, partly due to the British. At the decisive moment, General John Gort, commanding the islanders, feared the risk of encirclement. He ordered a withdrawal from Arras further north, closer to the sea and their homeland, the Foggy Albion. One can only imagine what feelings overwhelmed Weygand at that moment: “The situation is worsening; the English are not advancing south but retreating to the ports.”

The French resented the British’s calculated behavior just as much as the latter despised the disorganization of their continental allies. Mutual prejudices deepened. And General Gort was unwilling to stand and fight to the death for France. An honest soldier, this officer was no military genius and, after the breach of the Maginot Line, thought less about allied duty and more about getting his men home.

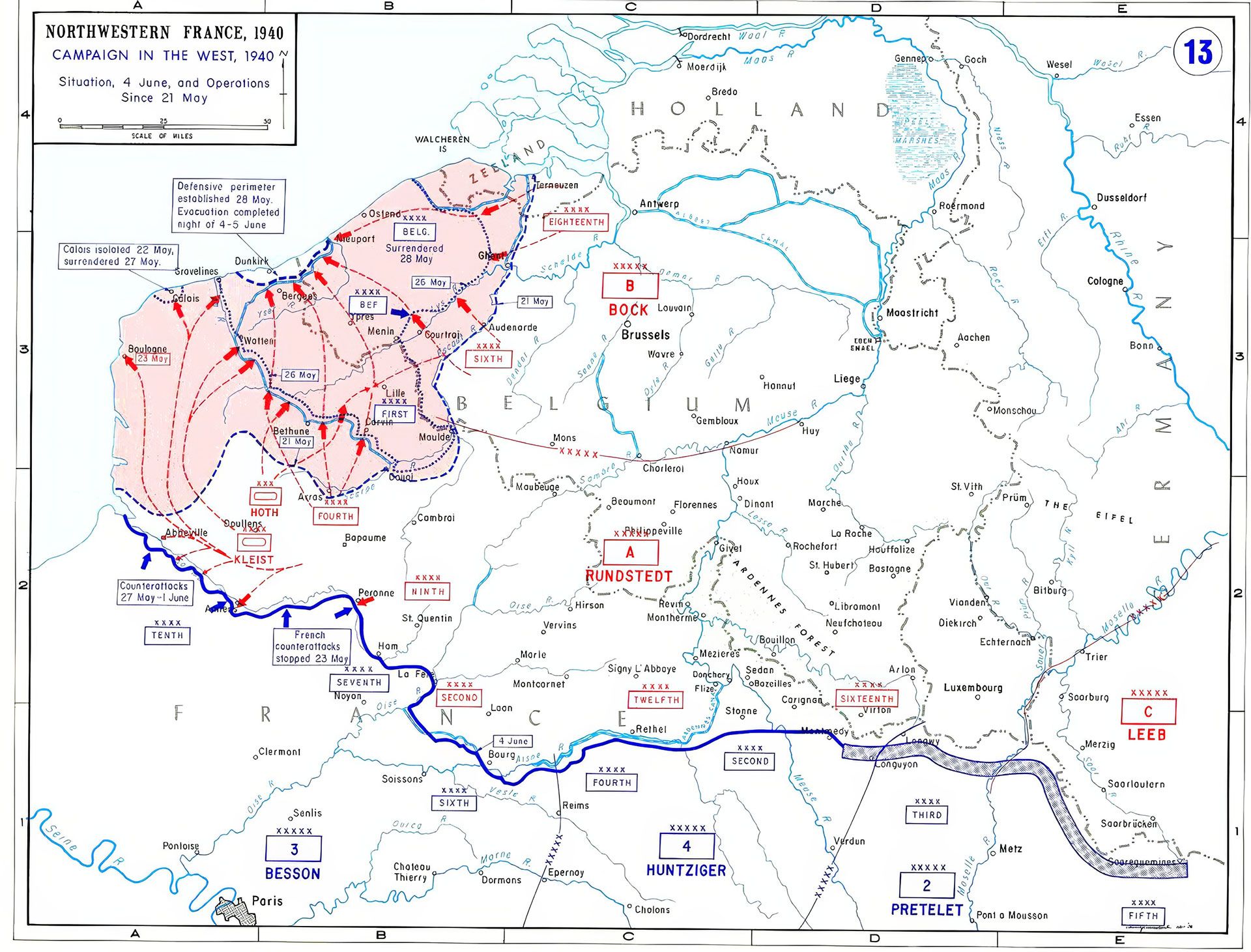

On May 19, Gort decided to head for Dunkirk and informed command at home of his intention to leave doomed France via the Channel. His reasoning was generally approved. By May 22, Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay had effectively begun preparations for evacuation. Officially, the British announced the launch of Operation Dynamo only on May 26 and notified their French allies then — a delay that did not foster trust between London and Paris.

The third ally, Belgium, was not informed at all by the British. However, Brussels was clearly in agony — the Nazis accepted its surrender on May 28.

“Our Task Is to Destroy”

Between these preparations, the event that later laid the foundation for the legend of “Hitler’s good will” occurred. On May 23, General Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of German Army Group A, ordered his subordinates to halt the advance near Dunkirk.

Rundstedt had no intention of sparing the nearby enemy forces. The German acted according to normal military logic:

1) The marshy terrain around Dunkirk was unsuitable for maneuverable tank warfare;

2) Army Group A had advanced about 350 kilometers from the Ardennes to the Channel in two weeks of fighting and needed rest and regrouping;

3) Losses of armored vehicles in some tank units reached 30-50%.

On May 24, Rundstedt’s decision was personally supported by Hitler. The dictator, as commander-in-chief of the German army, arrived at the general’s headquarters in Charleville-Mézières, reviewed the situation, and signed Supreme Command Directive No. 13. Years later, historians would interpret it as a lifesaver for Gort’s men, although at that moment the Führer (as always) was not thinking about mercy for the enemy.

The first point of the document clearly stated:

“Our immediate operational task is to destroy by concentric attack the Franco-British-Belgian forces encircled in Artois and [French] Flanders [two historical regions in northern France], as well as to reach the coast of the English Channel in the previously indicated area and consolidate our position there.”

But the devil was in the details. Hitler and his circle judged that Gort’s group and the attached remnants of Franco-Belgian forces were demoralized and disorganized. Crushing them was not a big challenge — infantry and artillery with air support could handle it. But the more valuable motorized infantry and tank units should be prepared for a breakthrough deeper into France, directly towards Paris (this was mentioned in the second, more detailed point of the directive).

The Führer was clearly haunted by the ghost of the Marne 1914. At the beginning of World War I, the Germans also successfully invaded France and occupied its northern regions but failed to capitalize on their success and decisively defeat the enemy. Therefore, in 1940, Hitler was eager to reach the south, considering clearing Artois and Flanders a secondary task. German generals agreed with this overall idea. It was believed the enemy was doomed: sea evacuation was impossible in wartime despite the deceptively short 75 kilometers across the Channel. In short, the “Tommies” had no option but surrender.

On May 30, German Chief of Staff Franz Halder joyfully noted in his diary that decomposition of enemy troops had allegedly begun in the Dunkirk pocket, with only a small part of the group holding the defense. But subsequent events on the Channel coast went contrary to Halder’s and his comrades’ expectations.

Nine Days for “Dynamo”

It is important to understand: while Hitler and his generals adjusted their plans, German soldiers at the front were not idling. Rundstedt’s “stop order” was local, and fighting resumed within a day.

On May 24, the 10th Panzer Division approached the port of Calais, only 42 kilometers from Dunkirk. Brigadier Claude Nicholson, commanding the tiny British garrison, refused to surrender and fought in a hopeless situation. Nicholson capitulated on May 27 but won 2-3 days, invaluable for the organizers and participants of Operation Dynamo.

All British officers around the Dunkirk pocket acted similarly, resisting fiercely, so the Allied “bag” shrank much slower than the Germans expected. The Nazis’ military bureaucracy also played into the British’s hands. Artois and French Flanders were transferred from Army Group A’s responsibility to the weaker Group B — this detail somewhat balanced forces near Dunkirk. Finally, the weather in northern France was persistently overcast before the summer, hindering Luftwaffe raids on the encircled.

However, the key factor was the work of the British Admiralty — with active help from parts of the French navy. By the end of the operation, Admiral Ramsay gathered about 400 military vessels and roughly the same number of civilian transports to rescue compatriots. Their crews, despite enemy submarines and aircraft, bravely approached the docks of Dunkirk and the second evacuation point, Malo-les-Bains beach, and took aboard soldiers who could hardly believe their luck.

Initially, British command expected the Wehrmacht to “give” them two days for Dynamo, during which sailors could evacuate 45,000 troops. But things did not go as planned: due to numerous difficulties (starting with shallow waters near Dunkirk’s beaches), the British evacuated only half that number on May 26-27. However, two pleasant surprises more than compensated for this setback. The Royal Air Force engaged the Luftwaffe in the effectively hostile skies in a roughly equal fight, and on the ground one of Gort’s corps commanders, General Alan Brooke — future Field Marshal and Chief of the General Staff — urgently reinforced the cracking Dunkirk perimeter.

As a result, instead of the planned two days, the sailors got nine. The gift from the Royal Air Force and General Brooke had a decisive impact on the operation’s outcome. The initial dozens of vessels turned into the aforementioned flotillas numbering hundreds of transports, from cruisers to fishing trawlers. Accordingly, the count of evacuated soldiers quickly rose from thousands to tens of thousands.

“Troop transports specially designed for sailing in the English Channel had the necessary speed and capacity. For example, the Royal Sovereign berthed at the east mole at 4:45, departed fully loaded at 5:45, arrived in Margate at 12:15, was unloaded in an hour and 15 minutes, and returned [to Dunkirk] at 17:30. At 18:20, the ship’s captain already reported that ‘troop embarkation from the shore has begun.’”

- David Devine, British historian

From May 26 to June 4, the Allies evacuated about 338,000 soldiers: around 200,000 British, more than 120,000 French, and roughly 20,000 Belgians, Dutch, and other allies.

The price of this rescue was, first of all, the abundant trophies for the Wehrmacht, which did break into Dunkirk. The Germans seized about 600 tanks, more than 2,300 artillery pieces, and nearly 64,000 military vehicles and trucks. The tally of captured ammunition, fuel, and supplies ran into thousands of tons. And these were not the only costs of Dynamo.

French Fury, German Indifference, and British Hope

One of the main paradoxes of the Dunkirk evacuation is that it did not strengthen but further weakened the already shaky Franco-British alliance. The British informed the Allied commander Maxime Weygand about Operation Dynamo only after it began, and some commanders learned about it even later. Naturally, French officers could not but see the evacuation as a cowardly flight of “roast beefs” behind the backs of a bleeding friendly army.

Especially since until May 30, the British — with rare exceptions — did not put foreigners on their ships in Dunkirk. After Churchill’s personal order, this misunderstanding was corrected, but precious days had already been lost. As a result, at least 40,000 Frenchmen failed to board the Allied ships and fell into German captivity. Thus, Dynamo drove another wedge between Paris and London, contributing in summer 1940 to the growth of defeatist and anti-British sentiments in France (indeed, General Weygand would become a prominent figure in the collaborationist Vichy regime).

“The English kept their evacuation plans from us, even though we maintained close contact. Of course, Paris eventually learned about them. And this significantly worsened relations between the two governments during this tragic period of our still common war.”

- Captain 1st Rank Offan, staff officer of the French Navy

Meanwhile, the German command calmly accepted the events on the Channel and its coast. The flight of enemy remnants paled against the triumphant entry of the Wehrmacht into Paris and the effective surrender of France on June 22, 1940. As Luftwaffe Field Marshal Albert Kesselring later admitted, the Nazis simply did not consider “that England and France managed to evacuate over 300,000 men. According to our calculations, even a number three times smaller would have been impossible.”

It should be noted that the Luftwaffe did everything to reduce this number. During Dynamo, German pilots relentlessly shelled and bombed both the enemy waiting for evacuation and the ships receiving them. At least 2,000 Allied soldiers died from Nazi air actions, and about 100 transports were damaged, including Red Cross-marked hospital ships. All this contradicts the theory of Hitler’s “good will,” supposedly wishing to appease the British and incline them to an armistice.

Yes, during those days the Führer spoke at length about having no grievances against Britain and the reality of peace between the two empires — provided the English extended a hand themselves. But these reflections did not contradict Hitler’s specific worldview and in no way meant a conscious decision to spare the enemy in Dunkirk. Simply, at the crucial moment, Hitler and his ground forces commander Walter von Brauchitsch saw a strategic priority in advancing deeper into France — and that calculation paid off.

In Britain, the success of Operation Dynamo was the first piece of good news since the war began. It is no surprise that the news of saving hundreds of thousands of soldiers was received almost as a triumph by His Majesty’s subjects. Although even Churchill, reporting on the Dunkirk outcome, allowed himself a rare wartime candor: “This must not be regarded as a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations,” he told the House of Commons on June 4, 1940.

Churchill’s government and the people who had not formally chosen him faced one of the most severe trials in national history. The United Kingdom was to stand alone for a year against the seemingly invincible Nazi empire. But that is another story.

Main sources of the article:

Dashichev V. “What Do the Sources Say About the Events at Dunkirk?”;

Devine D. “Nine Days of Dunkirk”;

Durandina E. “The Beginning of the End for the French: Chronicle of the Operation at Dunkirk”;

Kotov A. “Did the British Abandon the French? 8 ‘School’ Misconceptions About the Dunkirk Evacuation”;

Liddell-Hart B. “The Second World War”;

Shirer W. “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich”

Main photo — evacuated soldiers from Dunkirk dining at a London station, May 31, 1940. Photo: Wikipedia / Saidman (Mr), War Office official photographer