Support the author!

«Anyone who consciously chooses not to have children is a deserter.» How the Ceaușescu regime lost the war on abortion

In late December 1989, after a series of chance events, Nicolae Ceaușescu’s dictatorship in Romania collapsed within days. Over a quarter-century in power, he ruined the lives of hundreds of thousands. The Ceaușescu regime enforced an absurd cult of personality, brutally suppressed any dissent, and plunged the country into a poverty so dire it stood out even among socialist states. Throughout most of his rule, the so-called “Genius of the Carpathians” waged a ruthless campaign against abortion. What were the consequences for Romania and its people?

One of Nine Thousand

History has not preserved the name of this woman. All that is known is that she lived in Sălaj County in northern Romania and turned 35 in January 1987. She did not live to see her thirty-sixth birthday.

She was brought to the hospital in the county center of Zalău with pregnancy complications. “Part of the fetus had already emerged, its forearm was visible,“ the authors of the medical report later noted. The woman needed urgent surgery, but the doctors in Zalău hesitated. Indirect signs suggested she might have attempted an abortion, which by then had been de facto banned for 20 years. Silence from the doctors in such cases meant complicity.

Frightened doctors immediately reported the new patient to the State Security Department, better known as “Securitate”. Officers from the agency immediately pressured the suffering woman from Sălaj to confess to the crime and give up the name of the abortionist. But despite the bleeding and excruciating pain, she insisted she had made no attempt to terminate her pregnancy.

There was a complicating factor. The patient was already raising five children, which put her among the few Romanian women legally allowed to have abortions in clinics. But the Securitate agents were relentless, demanding a confession and refusing to let doctors treat her. After five days of nightmare, she died.

The tragedy of the unknown woman from Sălaj is just a drop in the ocean of similar cases. Romanian archives from the Ceaușescu dictatorship confirm that from 1967 to 1989, at least 9,451 women died in similar circumstances. Their lives were cut short by the pro-life legislation in force.

It is much harder to estimate how many Romanian women suffered various humiliations from their superiors during this period. Some were subjected to rough medical exams right at work and then forced to write explanations about why, despite being healthy, they still had no children. Others were made to sign statements for the police, acknowledging they knew about the punishment for abortion and would not attempt it. Still others had to prove through numerous authorities that, contrary to someone’s denunciation, they had not tried to terminate a pregnancy—there were even cases where virgins had to do this.

Romanian communists, unable to provide even a semblance of normal life for their citizens, stubbornly forced them to reproduce. This coercion brought nothing good to the country or its women.

Unhappy Sevens

The Ceaușescu regime was fundamentally different from other “people’s democracies” (leaving aside Tito’s Yugoslavia and Hoxha’s Albania, which took their own paths) thanks to an important nuance. In the late 1940s, power in Bucharest was seized not by Comintern émigrés returning with Soviet troops, as elsewhere in Eastern Europe, but by the so-called “prison faction.” These were local underground communists, often imprisoned under the old pro-fascist regime.

The leadership of the Romanian Workers’ Party was not made up of people who had lived in the USSR and looked to the Kremlin for guidance. Both the first leader of the new socialist republic, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, and his entourage espoused a strange mix of Marxism and nationalism. The idea was: Romania is a special nation, descendants of the ancient Dacians and heirs of Rome, the only Latin island in a hostile Slavic sea. Nicolae Ceaușescu, who inherited party leadership from Gheorghiu-Dej in 1965 and then established one-man rule, also believed this.

Ceaușescu sincerely believed Romania could be, if not a European China, then at least a European North Korea. That is, formally a client of Moscow, but in reality pursuing an independent policy and taking advantage of the Cold War’s chaos. But for this, in the Bucharest leader’s view, all citizens had to work—not just in offices, fields, and factories, but also in their bedrooms. From the start, Ceaușescu insisted Romania’s greatness depended on increasing its population from 19 million in 1965 to 30 million by the end of the 20th century.

The fetus is the property of society as a whole. Anyone who consciously chooses not to have children is a deserter, betraying the laws of national continuity.

- Nicolae Ceaușescu

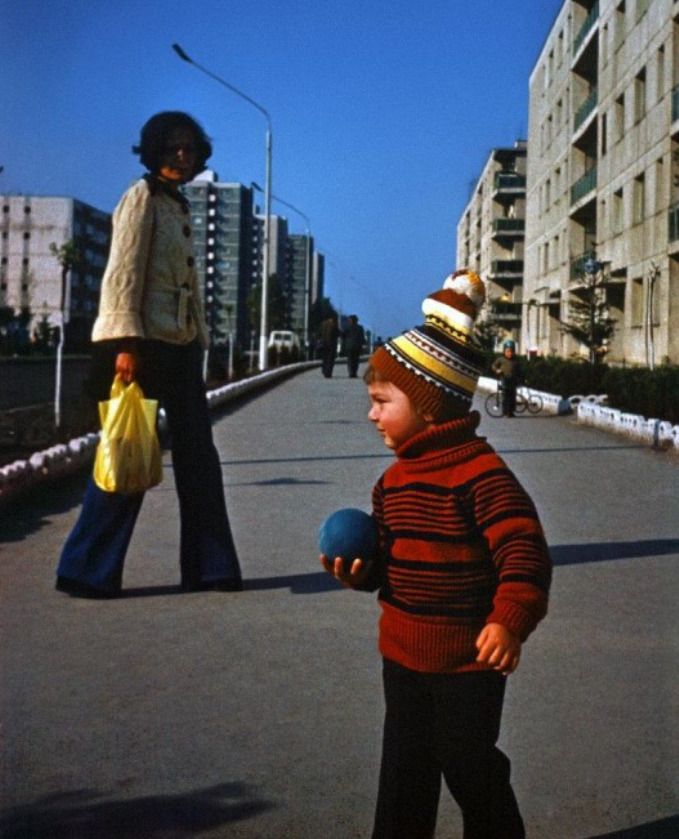

But in the early 1960s, the birth rate in Romania was falling. The communist leadership was pushing rapid industrialization. In the first 20 years of the new order, about a fifth of Romanians moved from rural areas to cities. They usually settled in hastily built high-rises on the outskirts of Bucharest and other centers. Compared to them, Soviet Khrushchyovkas would have seemed like social paradise. Elderly Romanians recalled that their housing often lacked even heating and running water.

Moreover, Gheorghiu-Dej and Ceaușescu were not aiming for the conservative social ideal of Kinder, Küche, Kirche. On the contrary, women were encouraged to study and work, even in the most “male” professions—welders, tractor drivers, assemblers, machinists. Under such conditions, would-be housewives simply could not have as many children as their mothers and grandmothers did. This was not surprising—Romania in the 1960s was experiencing the demographic transition inevitable in all countries: declining birth rates always came as the price for lower child mortality and more educated urbanites.

But Ceaușescu, who had barely completed primary education, did not understand any of this. He blamed the problems with reproduction on the laxity of citizens and the ill will of Gheorghiu-Dej, who legalized abortion in 1957. The new dictator’s simple logic was that if one bureaucratic act had made Romanians lax (by 1965, the number of abortions exceeded a million), then other acts, in the right spirit, would whip the people into shape. Ceaușescu’s will was not long in coming.

On October 1, 1966, the Council of Ministers approved anti-abortion Decree No. 770. At the time, few in the Romanian government thought the document would lead not to happy large families, but to thousands of ruined lives—both adult and child.

A Concerned Policeman and a Two-Faced Director

Officially, the ill-fated decree did not completely ban abortion. Romanian women could terminate unwanted pregnancies in certain circumstances. The procedure was legally allowed for:

- women over 45 (later lowered to 40, then raised back);

- those who had already given birth to four children (later raised to five);

- pregnancies resulting from rape or incest;

- cases where the mother’s life was at risk or the fetus had severe abnormalities.

But for the vast majority, abortion became inaccessible—the number of legal procedures fell from a million annually in the late 1960s to a few thousand. The same decree also removed newly available contraceptives from free sale. Naturally, unwanted pregnancies soared. Ceaușescu was not satisfied yet.

In the late 1960s, the Bucharest regime—officially Marxist and atheist—realized other dreams of ultra-conservative clerics worldwide. Socialist Romania criminalized homosexuality and banned all forms of sex education (in 1977, a 10% tax on childlessness was added). Divorce, like abortion, was not formally banned, but in practice, only couples where one spouse had emigrated or suffered from mental illness could divorce without humiliating investigations.

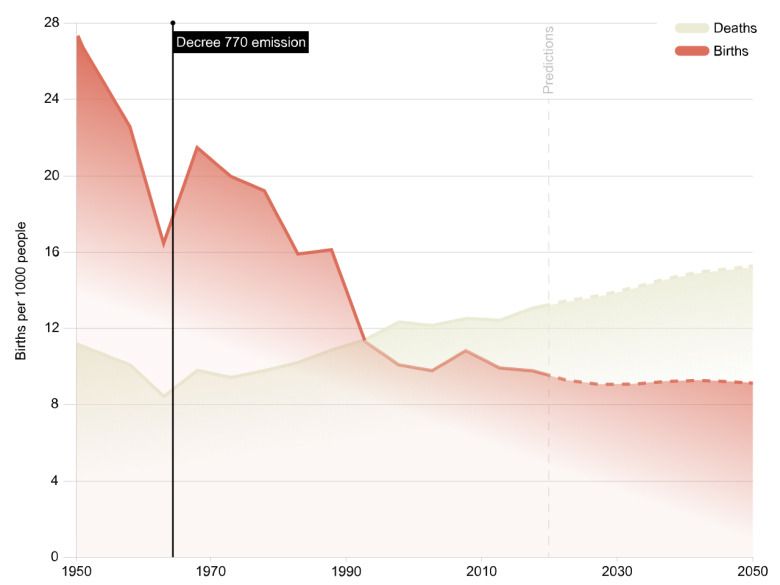

For a moment, the regime achieved a stunning result. In 1967, Romania saw an incredible demographic leap. The fertility rate almost doubled: from 1.9 to an “African” 3.7 children per woman. In the first five years of Decree No. 770, the population grew by nearly 1.2 million—almost 6.5%! It seemed the republic would reach Ceaușescu’s target of 30 million citizens long before 2000.

But then the silent majority began to sabotage the experiment. By 1973, the fertility rate had dropped by half compared to 1967, down to a middling 2.4 children per woman. The regime responded by tightening controls: in September 1973, Interior Minister Emil Bobu ordered police and state security to oversee all medical commissions authorizing abortions.

As a result, women from ordinary families were rarely allowed the procedure—even if they fit the exceptions in Decree No. 770. Things were different for the chosen few: women in high positions, wives of prominent party members, security officials, and favored cultural figures. They were quietly granted abortions without valid reasons.

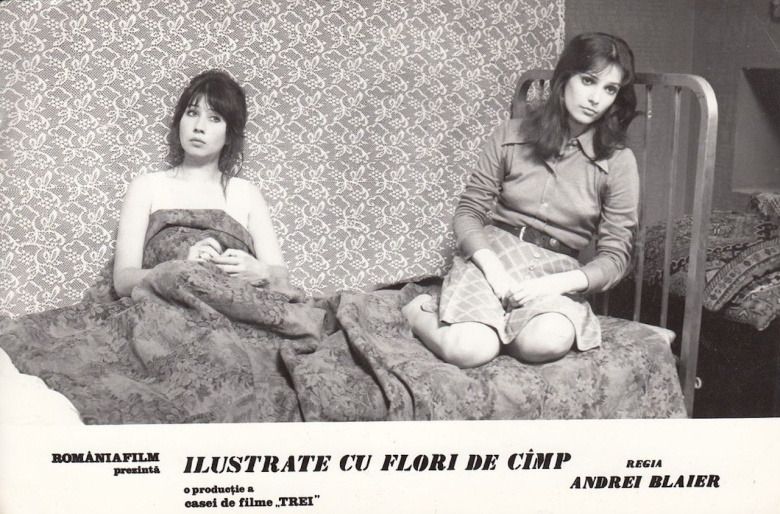

After the dictatorship’s fall, court director Andrei Bayer admitted that under Ceaușescu, he twice arranged for his wife to have an abortion. The grim irony is that in the mid-1970s, Bayer made a propaganda film “Postcards with Wildflowers (Ilustrate cu flori de câmp, 1975), warning Romanian women against underground abortions. In the film’s finale, the main character—who wanted an illegal abortion—dies, and her friend, overcome with guilt, kills herself.

Thirty years later, the new Romanian cinema would respond to “Postcards” with the drama “4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days” (4 luni, 3 săptămâni și 2 zile, 2007). The plot is similar: Ceaușescu’s era, two friends, an illegal abortion. But the ending is different—though there’s no happy ending, no one dies. The unpleasant operation succeeds, and both friends survive.

For a Handful of Dollars

The campaign launched by Minister Bobu in 1973 brought a small success. The next year, births jumped from 379,000 to 428,000. But in the late 1970s, the trend declined again—despite propaganda and tight control over medical commissions.

In 1979 and 1984, new Interior Minister Gheorghe Homostean reviewed the policy. He realized that enforcing Decree No. 770 no longer depended on doctors and their police overseers. By then, most women facing unwanted pregnancies avoided official structures and, like Bayer’s heroine, went for clandestine abortions. Homostean ordered surveillance of all Romanian doctors qualified to perform abortions and flooded medical institutions with informers.

The minister’s logic seemed clear: control the certified doctors, and no one will be able to perform abortions. In reality, things went against Bucharest’s calculations. Yes, frightened professionals did perform fewer illegal operations. But their place was gladly taken by thousands of unqualified and self-taught practitioners. Romania developed a thriving “black” abortion industry—with all the consequences that entailed.

Over time, the pathology of abortions changed, as unqualified practitioners entered the market. In the 1970s, women came to us with minor bleeding, were hospitalized for a day or two, and then discharged. In the 1980s, more and more women came in with infections, serious illnesses, and late-stage complications.

- anonymous Romanian doctor (as quoted by American sociologist Gail Kligman)

The regime decided the screws were still not tight enough. The Interior Ministry and Securitate recruited more informers, specializing exclusively in enforcing Decree No. 770. By 1989, it is estimated that each Romanian county had 50-70 informers watching over pregnant women.

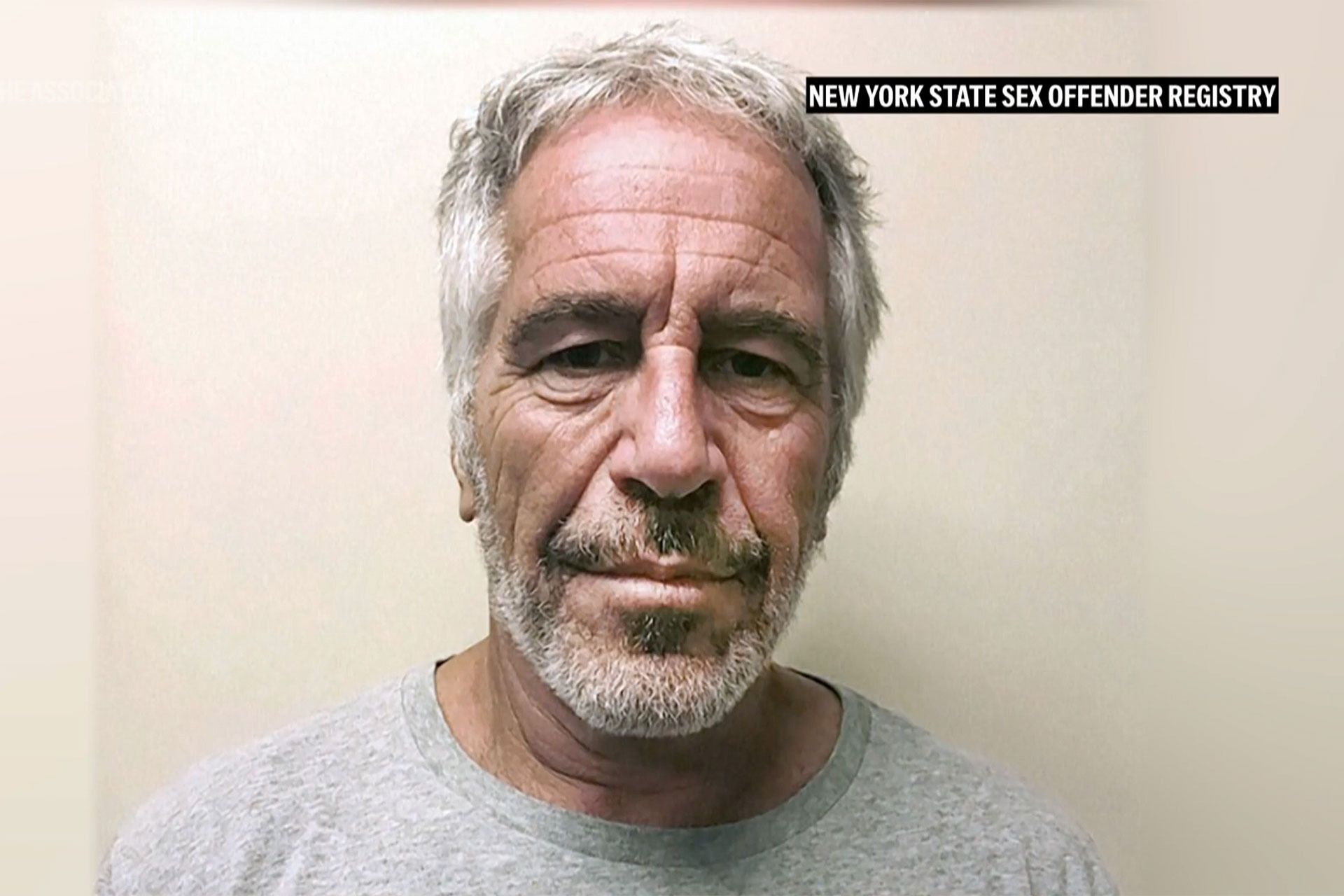

Declassified security archives now reveal hundreds of such informers. For example, Dr. Gheorghe Toabeș “worked” in Vâlcea County in the south. Over the years, Toabeș reported thirteen neighbors to the Securitate. Twelve were caught merely intending to have abortions and got off with warnings. But one was caught after an actual operation. She was prosecuted, and the informer received a small bonus of 200 lei; just over $30 at the official rate, about 10% of the average salary.

At the same time, security forces conducted a ruthless hunt for illegal abortionists and their clients. If in 1974 the regime conducted fewer than 250 abortion-related court cases, by the late 1980s the number rose to 1,300–1,350 annually. According to modern researcher Florian Soare, in practice only about one in five women actually served time. Usually, those caught performing self-induced abortions—such as by puncturing the uterus—were imprisoned. Those who used (and usually named) abortionists were fined or sentenced to corrective labor.

The “black” practitioners themselves were treated much more harshly. Courts rarely gave them less than three to five years in prison, and if a woman died, the sentence rose to 10 years. But new practitioners always replaced those caught by the authorities.

“I Would Have Killed Him for That Decree Alone”

Neither the risk of criminal prosecution nor the fear of death stopped desperate Romanian women from seeking banned services. The sky-high fees of underground abortionists did not deter them either: by the end of the regime, a single operation cost 5,000–10,000 lei—about two to four average monthly salaries.

The consequences of clandestine abortions, combined with the appalling state of Romanian medicine, multiplied maternal mortality. By 1989, there were about 169 maternal deaths per 100,000 births in Romania—much higher than even in Hoxha’s Albania, the statistical bottom in Europe at the end of the Cold War. This fact alone explains why Romanian women were so reluctant to give birth. Many, especially in cities, also feared they could not feed a child—under Ceaușescu, the country lived in dire poverty even by the standards of other socialist states.

From the mid-1970s, all citizens paid for the dictator’s ill-conceived policies. In his early years in power, he took out massive loans from the US and Western Europe, which were soon squandered on giant, unprofitable construction projects. Romania repaid its debts through total austerity—even heat and electricity were rationed in residential buildings. Unsurprisingly, by the end of the regime, the fertility rate had dropped to 2.2 children per woman—almost back to its original level. The total population in 1989 was just 23 million—likely, the small increase came from rural areas, where people had many children even without government coercion.

Another consequence of Decree No. 770 was a spike in infant mortality. Between 1967 and 1989, about 10 million children were born. But 340,000 of them died before their first birthday.

- Manuela Lataianu, Romanian sociologist

In the winter of 1990, just after the fall of the communist dictatorship and Ceaușescu’s execution, Western journalists interviewed many witnesses of the regime. One was 29-year-old Bucharest resident Maria Dulce, who had just survived an illegal abortion and removal of her uterus. She had the life-threatening operation while the “Genius of the Carpathians” was still alive; the new authorities repealed Decree No. 770 as one of their first acts.

Dulce told an American Newsweek correspondent that she terminated her pregnancy because of poverty. All her and her husband’s income went to support their two children, the youngest just 18 months old. With their last money, Maria and her husband bought a heater for the baby’s room and paid for the illegal abortion. Dulce did not hide her joy that the president under whom she had spent her whole adult life had been executed: “I would have killed him for that law alone.”

Cursed and Forgotten

The story of Decree No. 770 is a tragedy not only for would-be mothers, but also for unwanted children. In Romania, they were ironically called ceausei and decreței: something like “Ceaushats” and “Decretians.” Those born in the artificial baby boom of 1967–1971 (about 2.5 million people) later recalled a lifetime of chronic deprivation.

Parents did not give “Ceaushats” enough attention; many did not hide from their children that they were born not out of desire, but by government decree. In schools, children studied in three shifts, classes of 40. Graduates faced a shortage of university places and jobs. They could not try their luck abroad—the borders were closed. And the 1989 revolution brought no happiness to this unwanted generation. As the market economy took hold, large enterprises closed or downsized, and young specialists suffered first.

A significant number of “Decretians” never knew parental love. Their biological mothers, unable to risk an underground abortion, took the path of least resistance. They dutifully gave birth to unwanted children—and handed them over to orphanages. By 1989, up to 170,000 children were in Romanian orphanages (almost 0.9% of the population), and about half a million minors passed through the system during Ceaușescu’s rule.

The totalitarian state did not care at all about the “excess” little citizens it had demanded be born. According to survivors of Romanian orphanages, they were run like prisons. Older children beat and raped the younger ones; in search of food, the children stole and begged; randomly hired staff offered no help. The situation was even worse in special institutions for “defective” children—those with congenital disabilities. These resembled leper colonies, where residents were seen as doomed from the start. Western volunteers and journalists who visited such institutions in the 1990s compared them to Nazi concentration camps.

The two things I remember most clearly, which will stay with me forever, are the smell of urine and the silence of so many children. Usually, when you enter a room full of children, you expect noise: talking, shouting, or crying. But these children made no sound, even though none of them were asleep. They lay in their cribs, sometimes two or three to a bed, and silently watched what was happening.

- Bob Graham, British journalist, Daily Mail

The fall of the dictatorship did not end these children’s suffering. The executed dictator left his successors with too dire a legacy for them to have time for unwanted children.

***

As we can see, the story of Decree No. 770 in Romania is more than just a failed experiment to boost the birth rate. It is the story of how one foolish man, having seized unlimited power, imposed his mad will, threatening thousands of lives and millions of people. And a fragmented society, lacking the courage for mass protest, turned into a nation of silent saboteurs and sly informers.

Enduring poverty, lack of rights, and pervasive absurdity, Romanians survived both the hated regime and the dictator himself. And then chose not to dwell on the dark past. In this sense, the final line from the aforementioned “4 Months, 3 Weeks…” is telling: “You know what we’ll do? We’ll never talk about this, okay?” But sometimes, “this” must be remembered.

Main sources for this article:

- Breslau K. Overplanned Parenthood: Ceausescu's cruel law

- Coman O. Guardians of the Decree: The Hidden World of the Anti-Abortion Enforcers

- Lataianu M. The 1966 law concerning prohibition of abortion in Romania and its consequences. The fate of one generation

- Kligman G. The Politics of Duplicity: Controlling Reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania

- Bazanova E. Record maternal mortality and thousands of orphans. How Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu forced women to give birth and what came of it

- Legeido V. “Children of the Dictatorship: How Several Generations in Romania Were Doomed to Life in Orphanages”