Support the author!

«All holders of Russian passports end up on the blacklist. There simply aren’t any white lists anymore»

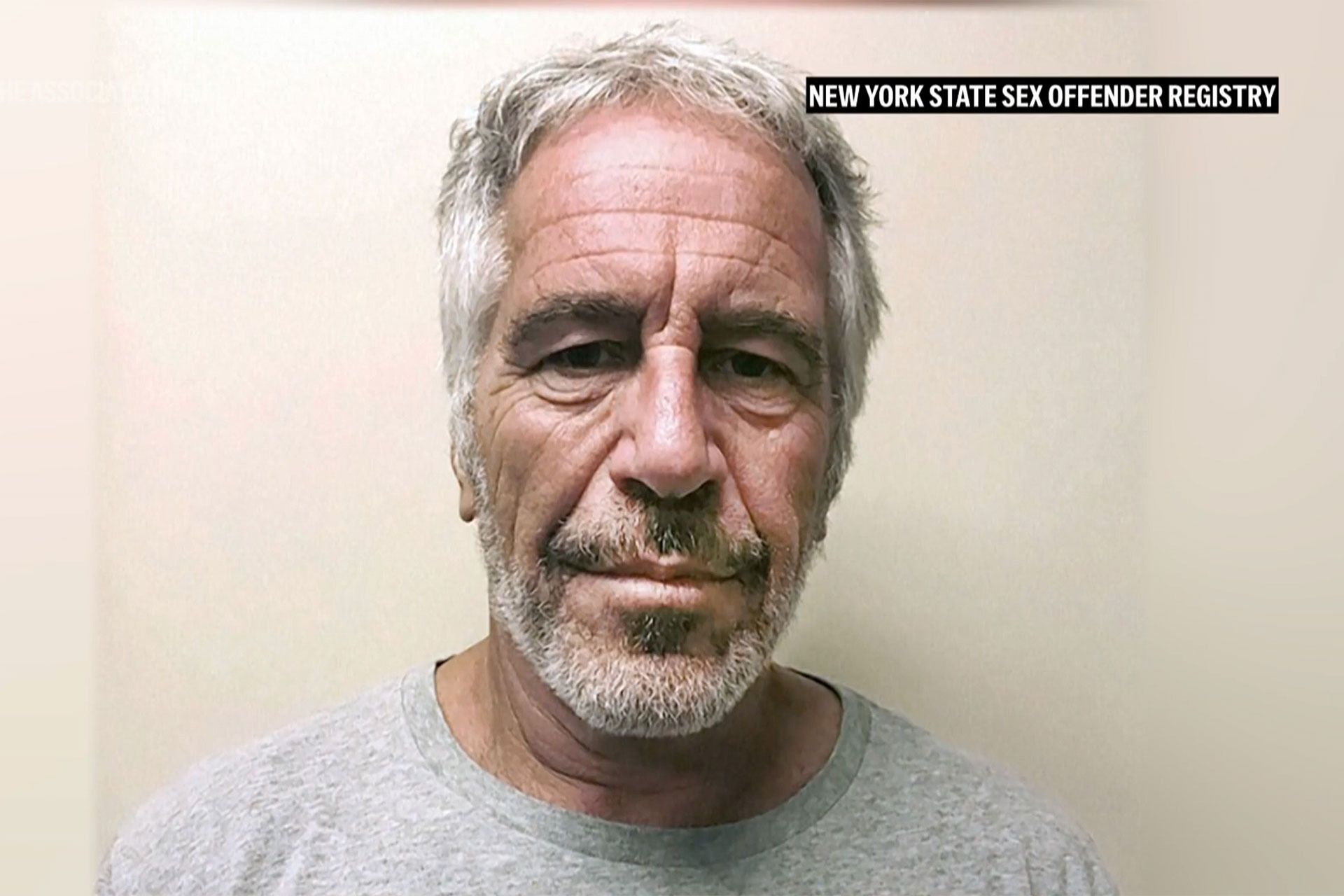

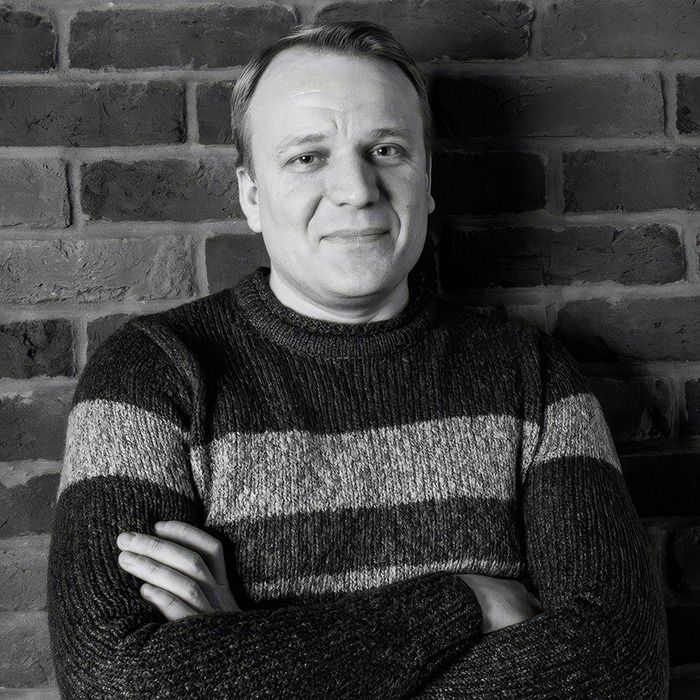

One of the main economic news stories this week for Russian citizens is the European Commission’s decision to include Russia in the list of high-risk jurisdictions. Officially, it is set to take effect at the beginning of January 2026. We speak with anti-corruption expert and founder of the NGO “Arktida,” Ilya Shumanov, about what problems to prepare for after the New Year holidays—and what his own plan is.

- On Wednesday, the European Commission published a decision to include Russia in the list of high-risk jurisdictions; officially, it should come into force in a month. Is there a chance it won’t? In this case, does it require the consent of all EU member states—or, say, could Hungary, whose prime minister sympathizes with the Russian political regime, protest and block the decision, as has happened before?

- The decision to include a country in this blacklist is made by the European Commission based on a combination of factors: it evaluates both the technical implementation of anti-money laundering recommendations and the political context. These are the two factors that led to Russia being included in the list.

By default, this decision should take effect a month after publication, but it can be postponed if further consultations or analysis are needed. If there is no consensus at the level of the EU Council of Ministers or the European Parliament, the decision won’t pass. But as far as I understand, there is already an agreed position from all sides. According to my information, the decision to include Russia in the EU blacklist was ready at the end of 2023 or the beginning of 2024. And by the end of 2024, the full justification for its adoption was also prepared.

Why wait until the end of 2025? I think the main strategy of the European Union was to wait and see.

- But this wasn’t just passive waiting. According to a recent study by the Finnish CREA Institute, in 2024 alone, EU countries spent €21.9 billion on oil and gas from Russia. Ukraine, which was attacked by Russia, received €18.7 billion in financial aid from the EU during the same period. And since February 2022, according to CREA, the EU has bought energy resources from Russia worth €205 billion, while total European aid to Ukraine over three-plus years of war amounted to €133.4 billion.

Do you think that including Russia in the EU blacklist means that from next year this surprising phenomenon will end? And EU countries will redirect all the money that used to go to Russia for energy purchases elsewhere—maybe even to help Ukraine.

- That’s a tough question…

- Seriously, the European Commission waits three years, and all this time EU countries continue to buy oil and gas from Russia in large volumes, despite all the sanctions. The money paid by Europeans is spent by Russia on the war in Ukraine. After the European Commission’s decision comes into force, any European bank will be able to block any transaction with a Russian counterparty. Will this finally prevent the EU from buying oil and gas from Russia?

- First: of course, restrictions will arise in all sectors without exception. Second: the decision to include Russia among countries with high risks of money laundering and terrorist financing goes hand-in-hand with decisions, for example, to restrict the supply of Russian gas to the EU by 2027. The EU is putting its foot down—Russian gas will stop flowing to Europe in November 2027.

- And that deadline is about two years away. There’s still time to buy up megacubic meters of Russian gas and store them.

- You’re right, but in addition, each EU country is required to prepare a plan to gradually reduce consumption of Russian gas. This is an obligation for every EU country. I can’t say it’s all so hypocritical. Of course, some countries say, “No, it’s more profitable for us to buy Russian gas and oil, and we’ll keep doing it,” but then they’ll have to forget about European subsidies. And those are five, seven, or ten times more beneficial than Russian gas.

The more complex the system, the harder it is to reach agreements, including at the EU level. And of course, there will be special conditions and exceptions that Russian companies can take advantage of. It’s impossible to break contracts [for LNG supplies to the EU] with, say, Novatek, because there are futures issued for them, storage capacities reserved, and so on. So, everything won’t collapse at once. But in the medium and long term, this will certainly have a big impact on major Russian suppliers. And it’s not just about oil and gas—there are also metals, fertilizers, and much more.

- European companies continue to operate in Russia because they couldn’t or didn’t want to leave—take Raiffeisen Bank, for example. What happens to them now?

- Yes, I really don’t envy Raiffeisen Bank and its management right now, especially in the Russian office. Why? Because they’re caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, they can’t sell the Russian division. On the other, a large stream of funds has flowed through Raiffeisen Bank, legally transferred from Russia to the EU.

Now Raiffeisen Bank will be in a paradoxically difficult situation, because the waiting strategy has led it to an even worse position than at the start. After the European Commission’s decision takes effect, all transactions by Russian citizens will have to go through so-called enhanced due diligence—meaning stricter checks on counterparties, their transactions, payments, sources of funds, etc. To process these transactions, Raiffeisen Bank would have to hire as many employees as it already has. It’s easier to close or wind down activities in Russia, make a deal, and hand over the office to some local company or bank. In reality, Raiffeisen Bank is already not handling transactions from Russian individuals to the EU.

European businesses operating in Russia have already found it nearly impossible to transfer funds out of the Russian Federation. All revenues of companies from so-called “unfriendly” countries are stored in special accounts. The further process of moving these funds is very complicated.

There’s another group of companies that dared to leave Russian jurisdiction and fell under review by the government subcommittee on foreign investment control, headed by [Russian Prime Minister] Mikhail Mishustin. These companies are now in limbo—they’re waiting their turn for Russian authorities to approve the sale of their assets to Russian or foreign partners.

I think the Russian authorities will respond asymmetrically to the step taken by the European Commission. What could they do?

It seems to me that traditionally the Kremlin acts this way: those companies that are “hostages”—that is, still operating in Russia—will have to suffer in some way.

Either their assets will be nationalized, or their activities made more difficult, for example, by imposing additional restrictions on citizens of EU countries. In other words, a demonstrative maneuver toward the European Union.

- In general, the political line we’re discussing has existed among European authorities since 2011, with the first personal sanctions against those involved in the Magnitsky case. So we’ve basically been living in this regime for almost 15 years. Does what’s happened now really make things significantly worse for Russian citizens in Europe?

- In principle, Western sanctions against Russia were initially very targeted. They concerned specific companies and individuals. It was a kind of “wall of shame”: everyone except those on the sanctions lists could travel to the EU and US and do business there—those on the lists could not. Then came sectoral sanctions, which restricted certain industries, regions, types of activity. The sanctions noose tightened gradually. In 2022, the pace of tightening increased. Since then, the EU has introduced 19 sanction packages, and it’s already hard to count everyone affected. The lists have swollen so much that it’s impossible to keep track.

And the fundamental difference with including a country in the blacklist, as opposed to sanction packages, is that there are simply no white lists anymore. All holders of Russian passports end up on the blacklist. In other words, they lose certain rights. With your Russian red passport, you’re seen as a higher-risk subject in terms of money laundering and terrorist financing.

How does this look in practice: a transaction comes through, a bank manager opens it and checks who it’s for. If it’s a North Korean citizen, a red flag pops up by their name, because they’re from a high-risk jurisdiction. The same goes for citizens of Iran, Afghanistan. And from next year—any citizen of the Russian Federation.

The reputational costs of Russia being added to such a blacklist will, of course, be felt far beyond the EU and will affect countries that work with both the EU and Russia. And these countries will have to choose: lose their euro correspondent accounts for their banks, or continue cooperating with Russia.

The choice in such a situation is obvious: to keep the ability to operate in euros, they’ll want to maintain relations with the EU. That means they will have to restrict Russian citizens’ rights and comply with restrictions introduced in the EU.

- The EU blacklist currently includes 27 jurisdictions, among which are recognized pariah states: besides Afghanistan and North Korea, there’s Iran, South Sudan, Myanmar, Syria, Venezuela. On the other hand, in June, when the list was last updated, Lebanon, Laos, Vietnam, Nigeria—one of the world’s largest oil producers, which Europe surely buys from—and even Monaco were added. So, do European banks treat all countries on this list the way you described? Or are some more equal than others? Does a citizen of Monaco also get a red flag when opening an account in a French bank?

- Yes, and moreover, I know of cases where people with Monaco passports had their Revolut accounts closed after the high-risk jurisdictions list was updated. And I understand why Monaco is on the EU list: it really does have a very weak anti-money laundering system.

What do we know about Nigeria? Yes, it’s one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa. But there are plenty of Nigerian corrupt officials buying real estate worldwide. The level of corruption there is quite high compared to other countries. Each country is different, of course…

- …corrupt?

- Not corrupt, but each has different corruption risks. In fact, one of the key elements of the anti-money laundering and terrorism financing system is monitoring politically exposed persons. High-ranking officials who can enrich themselves illegally by accessing the state system are automatically high-risk for laundering, regardless of which country they’re in. And if the country is on the high-risk jurisdictions list, it’s a compliance officer’s nightmare. Now, the family of a Russian official is a huge red flag.

- However, such politically toxic figures and their associates often simply obtain passports from other countries—Croatia, Bulgaria, whatever—and present those passports when opening accounts in European banks. What will this EU blacklist change for them?

- Indeed, there is such a procedure for obtaining citizenship—often a personal decision by a country’s leadership. For example, there’s a strange story about high-ranking Russians getting Serbian passports, and there are “golden” passports from Malta or Cyprus.

- Or remember how Pavel Durov got French citizenship.

- Yes. But here, it doesn’t make sense to single out France. A passport from any country can be granted for special merits. For example, Vitalik Buterin, creator of “ether” [the Ethereum cryptocurrency], got Montenegrin citizenship. Countries hunt for big businessmen, tech magnates—it’s not just about reputation, but also about taxes, and that’s normal.

But now all possible schemes for obtaining an investment passport or visa are de facto closing for Russians—at least in the EU or the European Economic Area, which is a bit wider than the EU. And now, just because the source of the money is Russia, many financial institutions will refuse to treat those funds as legally acquired.

- In June, when 10 countries including Monaco were added to the EU blacklist, several others were removed. Among those removed were, above all, the UAE, where much Russian capital has moved due to Western sanctions. Or, for example, Barbados, which sold passports for investments starting at $230,000 and had simplified entry rules for Russians. So, if a country ends up on this list, it’s not forever.

- Right, but I’ll remind you how the United Arab Emirates got off the list. Money laundering problems still exist there. But the Emirates launched a series of reforms to counter corruption and money laundering in various sectors—for example, real estate, crypto services, and so on. I can’t say they’ve made huge progress, but at least they have a plan, it’s been accepted by the FATF, and as far as I know, at the international level, the removal of the UAE from the list was discussed with the possible addition of Russia. Some Arab countries were determined to keep the UAE as a partner, not Russia.

For the EU, the Emirates are an important economic partner; no one is cutting ties with them. The real issue was that the UAE became a hub for laundering Russian money, a transit point for bypassing sanctions. And the EU didn’t like that. In the end, it was a political trade-off.

Strong lobbying by the Emirates also played a role: they pressured certain EU countries, and those helped the UAE get off the list in two or three years.

- So now wealthy Russians will launder their capital through the UAE with even more energy?

- No, their transaction costs will rise, so it won’t get easier. Now, for example, a Russian citizen opens a company in the UAE and can freely conduct euro transactions with EU partners if it’s not a sanctioned business. For example, importing phones from one country and selling them through the UAE to Russia. After Russia’s new status formally takes effect, such operations will be more difficult. Because European banks will be looking at who the ultimate beneficiary is. If it’s Russian citizens, there will be questions.

- There’s a practice of using front men—“drops” with EU residence permits—to bypass Western sanctions against Russia. Obviously, the European Commission’s decision will hit that practice, but it can still be circumvented. For example, by hiring drops with EU citizenship. That’s also a matter of transaction costs, of course.

- Yes, it’s all about transaction costs and declining quality of life. You can hardly say citizens of North Korea or Iran feel good in the EU.

Living without access to financial services, using a drop’s card, and waiting to be caught and expelled from the EU is no pleasure. In a digital state, there are almost no options to exist in a reality parallel to the state.

You’re forced to interact with either the private financial sector or government agencies, because you need to maintain your social status, have legal standing, not be someone excluded from all financial processes and paying only in cash.

- Have you come across any specific cases involving Russian companies, including sanctioned ones, and drops with EU residence permits?

- You just have to go to the dark web and see how Russian-language shadow forums sell business accounts with connected banking or payment services from EU countries. The transaction limit is about a million dollars. Obviously,

these accounts are registered to nominees. For example, Ukrainian citizens with EU residence permits, or residents of the Baltic states. There are a lot of such offers.

Eastern Europeans cost a bit more as shareholders or owners of such companies. Nominees from Western Europe are hardest to find—and cost two or three times more than a Ukrainian willing to be a nominal owner.

- And how much do the services of such a drop cost?

- Not very expensive. I won’t name prices, because that would be advertising such a way of earning money.

- Who uses drops from the EU? Who needs this most often?

- People engaged in parallel imports, for example, who can conduct such operations. Or pure dirt: drug dealers, child pornography sellers, financial fraudsters.

Ordinary people also get caught up, who just need to transfer money. They don’t understand how to organize a legal transfer procedure without big losses. So they try to use these things.

But now it’s much easier to move Russian-origin money through cryptocurrency. That’s now a bigger, more acceptable model for a wide circle, including business.

Remember the story of the son of the former Krasnoyarsk governor, Artem Uss? A sanctioned Venezuelan state company sold oil to a company of a Russian oligarch and received crypto as payment. [The governor’s son] Artem Uss was at the center of the scheme, helped its participants, and used the proceeds to buy dual-use goods, which were then supplied to Rostec. He made money on these transactions.

It’s a complex process that can involve shell companies, nominal directors and owners, and “factories” producing fake documents that just forge invoices. But it all gets uncovered pretty quickly. Usually, such schemes last no more than one or two years. For those supplying dual-use goods, that’s enough. You can throw someone under the “justice train” and find another intermediary, who’ll open a scheme through Hong Kong—which is now trendier than the UAE.

- You are a well-known anti-money laundering expert and at the same time a Russian citizen. Obviously, the European Commission’s decision to include Russia in the high-risk jurisdictions list will affect you personally. What’s your plan?

- The simplest plan and solution is not to play cat-and-mouse, not to try to trick the system, because every move is recorded. When you get a residence permit or some kind of visa, you declare a lot of information about yourself, which is enough to check whether you’re telling the truth. I think this is critically important for any citizen of any country with EU residency.

Already, there are restrictions in the EU for Russian citizens who are EU residents on access to accounts in Russian sanctioned banks—regardless of whether you’re an EU citizen or got your residence permit yesterday.

So, if you have an account in Sberbank, which is under EU sanctions—in some EU countries, bypassing sanctions is already a criminal offense. Even paying utility bills for an apartment you rent out in Moscow, or sending money to a relative via Sberbank Online, could be interpreted that way.

There are already many such restrictions, but so far the EU is fairly lenient about them. There’s no hunt for Russian citizens with EU residence permits—yet. Though there are cases, for example, in the Baltic states.

As for me personally, I don’t plan to play the game of nominal directors or owners. The very fact of a country being on the EU’s black or grey list doesn’t mean I’m not allowed to receive money or sign contracts. I’ll just have to spend more time justifying my transfers and transactions. That is, I’ll be more thorough in gathering documentation, explaining to my contractors and counterparties where my money comes from, how I conduct operations, who I am, why I’m involved. Maybe that won’t be enough. Time will tell.

It’s still possible to conduct transactions outside the EU. There are third countries in the Global South that aren’t involved in this process—there, Russian citizens will face fewer risks.

But for those who are in the EU, you need to be ready to justify and argue your case. In case of unfair or illegal actions by financial institutions, don’t be afraid to go to court. I’m ready for that myself and will recommend the same to people who contact me. In cases of clear discrimination in financial institutions, I’d recommend suing. The European judicial system is stable and open to protecting human rights, regardless of what passport you hold.