Support the author!

What does Russia’s future look like after Putin? Scientific Director of the Levada Center, Lev Gudkov, responds

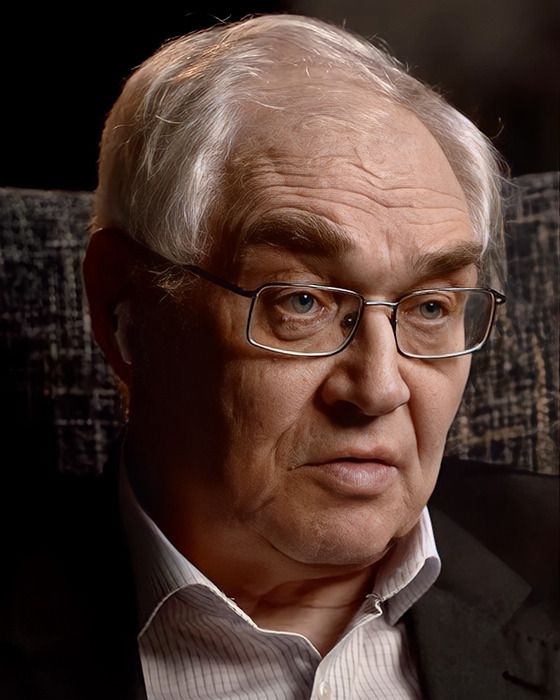

Sociologist Lev Gudkov has been studying public attitudes in Russia since the time of Perestroika. In the late 1980s, he worked at the All-Union Center for the Study of Public Opinion, from which he left in the early 2000s along with Yuri Levada’s team. From 2006 to 2021, Gudkov headed the Levada Center—the largest independent organization conducting sociological surveys in Russia—and then became its scientific director. Both the Levada Center and Gudkov himself have been designated as foreign agents by the Russian Ministry of Justice. Drawing on years of sociological surveys of post-Soviet society and the historical experience of countries that went through fascism in the 20th century, we spoke with the renowned researcher about the most likely scenario for Russia’s future.

- In your opinion, what awaits Russia in the future? Naturally, I mean the future after Putin: what is in store for the country under his rule is generally clear.

- In my view, a bureaucratic system has developed in Russia today, which will continue to reproduce itself even after Putin. Unless, of course, there is some extremely severe crisis. So far, there are few signs of such a turn of events, apart from Prigozhin’s mutiny.

What we are currently seeing in our surveys is the consolidation of the masses around the authorities, based on a very deep neurosis—if we can make such an analogy between society and the consciousness of an individual. This is connected to the failure of democratic reforms. Out of spite, we will continue this war, support it. Although all the indicators from the past year show that (in Russia) people are already very tired of the war. The ratio between those who want to continue the war until a victorious end and those who want to start peace negotiations immediately is about 1 to 2. As of the end of November 2025, that’s 26% versus 65%.

But if we start to ask what the negotiations should be about, the picture reverses—negotiations should only be about Ukraine’s capitulation. That is, if Putin decides to end the war and withdraw troops from the occupied territories, this will lead to a drop in his ratings and intense dissatisfaction.

In general, all these war years, as during other military campaigns under Putin, we observe consolidation around the authorities, a decrease in all complaints against them, a calming, a reduction in fear, and an increase in satisfaction with life—even without any particular economic basis for it. After all, practically all systems are degrading, including the social system. For example, the number of elderly people is rising, while the healthcare system is falling apart.

- I agree with you. But in addition to the degradation of Russian education and healthcare, there is also a monstrous moral and ethical degradation of the people. State officials, journalists who have become propagandists—like Dmitry Medvedev or Vladimir Solovyov, and many others—speak about the need to destroy Ukrainian cities along with their inhabitants, threaten Europeans with mass killings.

The Soviet regime committed terrible crimes both in its own country and abroad; for instance, in Afghanistan, Soviet troops killed between 1 and 1.5 million people, the vast majority of whom were civilians. But even so, in the USSR there was almost never such misanthropic rhetoric in mass propaganda (except perhaps for some articles by Ilya Ehrenburg at the end of World War II), as there is now in Russia. On the contrary, in words, in mass propaganda, the Soviet authorities stood on humanistic, internationalist positions. Today, Russian bloggers who promote hatred and mass killings have millions and hundreds of thousands of followers on Telegram, and no one in Russia is prosecuted for it. More than that, they are the regime’s support.

At the same time, Putin, who nurtures and supports all of this, plans to live forever. He has been in power for 26 years already, and with current advances in medicine could easily rule for as many more. Will Russian society be able to revive after all this?

- It’s not just a degradation of Russian society, but also a cynical adaptation to a repressive state. This continues and will continue. Firstly, because (in Russia) there is no idea that other types of relationships with the authorities are possible. Or if there is, it exists only among a very small, more educated segment of the population. According to our data, it’s just a few percent, and this share has been shrinking over the past few years.

Secondly, the entire preceding culture that we had is a hypocritical adaptation to the existing order, to the repressive state. This state has developed its own type of person, living their own life and demonstrating surface-level loyalty to the authorities, on the condition that this display of obedience keeps them safe. This experience from Soviet times has been revived during the decades of Putin’s rule. There was some weakening of this state in the 1990s, but back then people didn’t want freedom—they wanted to improve their consumer status, to live like in Western countries, but without doing anything for it, expecting that the authorities would provide such a level of well-being.

The basic type of person that we described back in the days of the August 1991 GKChP was always rather amoral: hypocritical, narrow-minded, sycophantic, revering superiors. Of course, this person is outraged by corruption, but if you dig deeper, you find that what outrages them is not its existence, but that they don’t get a share of it.

In other words, there’s a different logic at play: “I’m just not in the right place.” But “to be by the water and not drink”—that is, not to take [bribes or kickbacks]—is unrealistic for such a person. Survival, both in Soviet times and now, has always been possible here only through a network of informal connections, which in turn creates at best doublethink, hypocrisy, sanctimony, and cynicism.

- Are changes possible in Russia under such conditions?

- Change is only possible if there is training of new bureaucratic personnel who have practical management experience.

- But who will train such personnel for today’s Russia?

- That’s exactly my point. Who will train them? There are no underground flying universities today, as there were, for example, in Eastern European countries in the 1970s–80s. At that time, in Poland and partly in the Baltic countries, there was covert work to form a different civic culture—under the guise of Catholic parishes or Polish “Solidarity,” workers’ or folklore organizations, as in the Baltics. In Russia, I know of no organizations of this kind, let alone on such a scale [in Poland, the number of members of the independent union “Solidarity” in the 1980s at one point exceeded the number of members of the ruling party – A.Zh.].

In our case, relatively mass civil society organizations only began to appear in the 1990s, and even then they survived mainly thanks to foreign grants. Of course, there were environmental, journalistic, and research organizations like our Levada Center, but it can’t be said that they enjoyed much popular support. They were isolated, and the general population viewed them very negatively. They were seen as covert “grant-eaters,” living on Western money. The only ones who enjoyed real authority were organizations of soldiers’ mothers, which arose during the First Chechen War, and to some extent “Memorial.”

It’s very difficult to break this feature of Russian political culture. Successful reforms of totalitarian regimes usually took place under the umbrella of military occupation. But Russia is too big a country for anyone—even the richest countries or groups of countries—to imagine helping it. And even among Russian reformers and democrats in the 1990s, the bet was on economic reforms. Economic determinism prevailed—a legacy of Soviet Marxist education. They didn’t realize that it was also necessary to reform the basic institutions of a totalitarian society: the army, the KGB, the judicial system. The KGB was partially divided, but in principle today’s FSB is an unreformed structure. There were no purges or lustrations. If you visit the FSB website, you’ll see how they openly position themselves as successors to the KGB-NKVD-ChK, completely denying any guilt before society and defending their right to unlawful repression. These institutions define the structure of power in Russia today; their ethics, spirit, and worldview are becoming the state ideology.

- In your opinion, is this ideology accepted by the Russian population today?

- It’s not so much that it’s accepted, but the population perceives it as a given, since there are no other influential political or ideological forces in the country today.

But if we recall world experience, after two decades of fascism in Italy, former fascist regime officials were banned from certain professions.

- The same measures were taken in postwar Germany...

- Absolutely right—Verbot. Nazi officials were largely barred from holding government posts and teaching in schools, and many were put on trial. We had nothing of the sort! In Russia, the trial of the CPSU ended in disgrace, and there was no assessment of the Stalinist state as criminal. So it’s no surprise that Stalin is now held up as a “highly effective manager,” as a model statesman... According to all our surveys, he tops the list of the most outstanding people in our country.

- We lived through Soviet times and remember Soviet history. It’s well known that the Soviet state committed terrible crimes against its own people, especially in the Stalin years, and against the peoples of other countries. For example, in Afghanistan, Soviet troops killed, by various estimates, between 1 and 1.5 million people. But even then there wasn’t the kind of misanthropic propaganda, calls for genocide, and mass killings of Ukrainians and Europeans that Russian TV and other Russian media, including electronic ones—not to mention pro-government bloggers—now broadcast almost daily. So the question arises: how will these people live on?

Another point is that despite the fact that propaganda was also total in Soviet times, in August 1991 in Moscow, about a hundred thousand people came to the White House during the GKChP and essentially overthrew the regime.

There’s also the example of Portugal, where the regime of dictator Salazar was overthrown by a group of military officers after his death, the country embarked on a democratic path, and is now a member of the European Union. Yet in 2007, Salazar took first place in a TV show poll to determine the greatest Portuguese person.

So my question is: what path might Russia take? On the one hand, we see that its current authorities are doing everything possible to make the stupefaction of the Russian population irreversible. On the other hand, as we saw in Moscow in August 1991, there’s a chance for democracy even after decades of brainwashing. On a third hand, the example of Portugal shows that remnants of authoritarian thinking can remain even in a country that overthrew a dictatorship and has followed a democratic path for decades.

- Nothing is predetermined. Of course Russia has a chance, but it’s a weak one.

As for the aggressive tone, the sadistic calls of certain people in Russian power, sociological surveys show that society, the population, does not really accept them. Nor do people in Russia much like extremely nationalist statements. People want some predictability, stability, and such statements don’t appeal to most, they offend their underlying moral sense. Even if that sense is flawed, it exists in a vague, suppressed state. The only justification—in the mass consciousness—for this public cruelty and aggression is the idea that Russia is at war not with Ukrainians, but with Ukrainian “Nazism” and “fascism,” “paid for by the West.” In this case, the anger and aggression of Russian propagandists gets justification and support.

- This is very similar to how in the USSR before the attack on Finland in 1939 they came up with the word “White Finns,” and in the eyes of Soviet people the war was immediately justified...

- In fact, all the arguments used in Stalin’s Soviet Union to justify and glorify the Winter (Soviet-Finnish) War of 1939–40 were repeated in relation to the war against Ukraine. So, once again, certain layers of political culture are being reproduced by the conservative power institutions of modern Russia. Some of these interpretations were reproduced in the school system and in the state’s philosophy, which was very weakly reflected upon by the democrats at the time. The latter offered almost nothing in return. For this reason, such arguments are taken for granted.

Notably, in the 1990s, the Soviet-Finnish war was seen by Russian society as an absolutely unjust and predatory war by Stalin. Today, people repeat Stalin-era arguments that the war was preventive, against Finns who were about to attack the Soviet Union. People don’t think about the fact that Finland then had 3 million people and the Soviet Union 190 million—completely incomparable. For them, propaganda rhetoric is more important than the factual side of things. People in Russia today think in the clichés provided by propaganda.

Nevertheless, despite all the propaganda, there is a growing desire in Russia today to end the war. People are tired of it.

As for the Portuguese support for Salazar, the problem of mass support for totalitarian ideologies like fascism or communism has been analyzed in detail in the works of Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, and others. In a situation of uncertainty, the average person tries to hand over responsibility for themselves to a bearer of superpower, a charismatic leader who knows what to do. This is a well-studied mechanism of transferring responsibility, trust to the party, the state, to power, which promises a way out of crisis, a dissolution in that power. The authoritarian syndrome is a serious thing. And what can we say about Russia, if we see how America voted for Trump? And that’s with all the democratic institutions, the balance of powers, and the stable democratic culture of that country. In Russia, this syndrome is even more important, especially as it is reinforced by hatred of the West.

- But all this leads to the self-destruction of the nation…

- Yes, I repeat, everything is heading toward slow degradation. Slow, because the regime has enough resources. And it’s not about Putin; he is merely the expression of everything worst in this country. His system is held together by the bureaucracy. It is the middle layer of the bureaucracy that gives it stability. The top can change—as a result of open conflict, clashes of interests, elite contradictions, and so on. But the inertia of the system comes from the bureaucracy, which has no replacement. No one, as I noted, is cultivating a different type of bureaucracy, and no one understands how to put it under control and make it accountable when the population refuses to participate in politics. According to our data, 80–85% of Russians surveyed do not want to participate in politics, saying that it’s a “dirty business” or that they have no time for it.

- Again, this is reminiscent of Soviet practices, when people in the USSR also distanced themselves from politics, realizing they couldn’t change anything in the existing system and simply retreated into their own shell…

- Exactly! It’s simply a way of existing and surviving, when all a person’s relationships are focused on family or small groups, and on consumption.

- On the question of the continuity of the current Russian system with previous forms of Russian statehood. I recently reread Lenin’s article “On the Question of Nationalities or of ‘Autonomization’,” where Ilyich writes that our entire Soviet state apparatus “was borrowed from Tsarism and only slightly smeared with Soviet varnish.” Does it turn out that our state apparatus is reproduced almost continuously, regardless of political upheavals?

- Indeed, the Bolsheviks took the apparatus of the police state and reinforced its worst features, turning partial control into total control. At the same time, the USSR became a completely lawless state, where the police were given the right to decide for themselves what was a crime and what was not. All this dates back to the laws introduced in Russia under Alexander III.

- So I ask again about changes in Russia. All normal people want them. But are they possible?

- Give me at least some signs or symptoms of these possible changes. So far, I don’t see them. The most likely scenario is Russia’s gradual slide into the status of a regional power, weak and corrupt, a kind of pariah state dependent on more powerful countries like China. Democratic states will build some kind of fence, a barrier, to cordon off this disaster zone—and the country will stew in it.