Support the author!

More than Two Thousand Hostages, Dozens of Victims, and Lies from the Security Services: 30 Years Since the Kizlyar and Pervomayskoye Terror Attack

In the winter of 1996, nearly twice as many hostages were taken in Kizlyar as in Budyonnovsk just six months earlier; in terms of sheer numbers, the terrorist attack in Dagestan remains the largest in Russian (and apparently world) history to this day. This crisis taught Russian ministers and generals that force is preferable to words, and any loss of life is better than losing face.

Exactly 30 years ago, on January 22, 1996, security officers were buried in Moscow. These were members of the Moscow SOBR who did not return from a mission to the North Caucasus to free Dagestani residents taken hostage by Chechen separatists. The newspaper “Kommersant” published a notable report on the funeral ceremony and the press conference of the security leadership at the time (read the report here). Today, it serves as a quality snapshot of that distant era—when the Russian state did not yet control all its claimed territory, but media close to the authorities could still publish the gritty truth of war without consequences.

The headline itself is telling: “Hungry Assault.” The fact is, in Pervomayskoye, federal forces suffered not only from poor weapon supplies but also from a basic lack of food and warmth. The security forces went into the decisive attack hungry and freezing, while nearby, the headquarters with top brass and journalists had no such problems. As one SOBR officer told “Kommersant” reporters, “We were so frozen that we didn't care what killed us: cold or a bullet. Good thing someone thought to bring vodka.”

But by the mid-2000s, these details and the tragedy of Kizlyar and Pervomayskoye as a whole had quietly been forgotten. However, those two dark January weeks in Dagestan in 1996 are crucial for understanding modern Russian history. In handling that hostage crisis on the fly, Russian leaders and their security forces developed algorithms they would follow for decades to come.

A Remake Nobody Asked For

The separatists' plan is easy to understand—they intended to repeat and surpass what they achieved in June 1995 in Budyonnovsk, Stavropol Krai (that tragedy was covered in detail by “Most”). Take hostages, bargain with Moscow for political concessions, and return to territory controlled by the “ChRI” leadership. And, once again, remind the world that Russian authorities are not only powerless to reclaim Chechnya, but can't even truly control regions neighboring the rebellious republic.

In the summer of 1995, after the Budyonnovsk tragedy, field commander Shamil Basayev secured a favorable ceasefire for his comrades from the federal authorities. It was shaky and violated many times, but lasted until late autumn. Then the separatists decided they had gathered enough strength to resume hostilities. In December 1995, “ChRI” forces engaged in a week-long battle for Gudermes. The federals held onto Chechnya's second city, but psychologically, the victory went to the militants—Russian society was once again convinced that its army was not winning the war.

“ChRI” leader Dzhokhar Dudayev decided to build on this success with a second major raid outside Chechnya. In the summer of 1995, the separatists spontaneously chose Budyonnovsk as their target. This time, Dudayev deliberately selected Kizlyar—a small (43,600 residents at the time), multiethnic town in northwestern Dagestan. On one hand, Kizlyar was geographically close, just a few kilometers from the Chechen border. On the other, it housed federal infrastructure: an Interior Troops unit, a military airfield, and a defense-related factory.

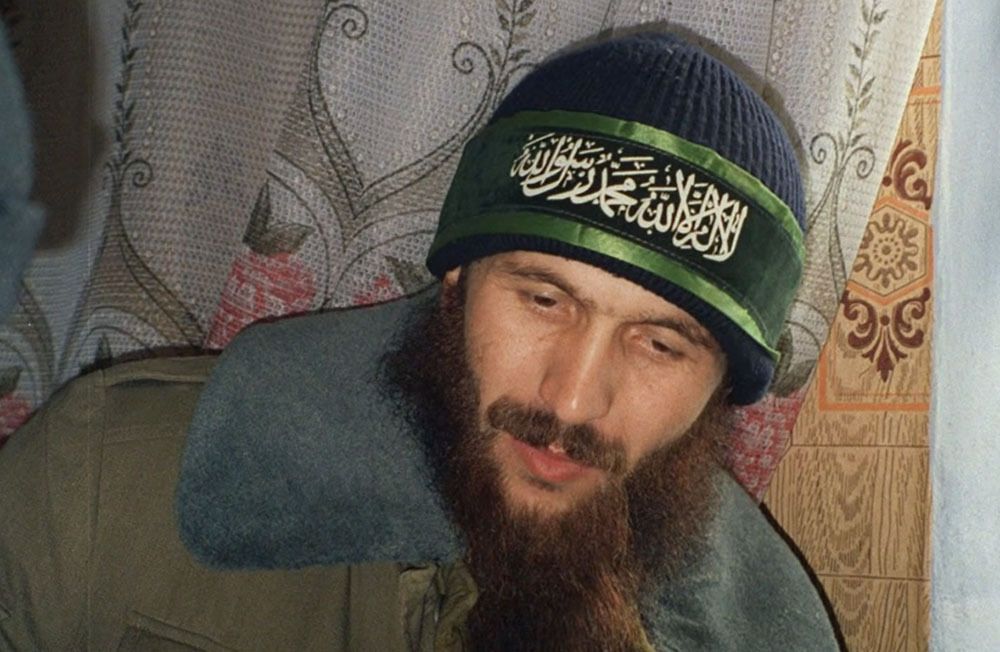

These were the targets meant to suffer the most damage, and, “by tradition,” as many hostages as possible were to be taken in Kizlyar. But Dudayev made a miscalculation when planning the raid. In Budyonnovsk, Basayev was the sole commander; for the new operation, two leaders were appointed. In practice, the militants were to be commanded by Khunkar-Pasha Israpilov, who had a higher military education from Soviet times and had fought in Nagorno-Karabakh (for the Azerbaijanis) and Abkhazia (on the separatist side). Politically, however, Salman Raduyev was to be the figurehead—his influence came from elsewhere: he was married to Dudayev's niece. Unlike most “ChRI” figures, Salman had no military or even criminal background. Until 1991, he was a loyal member of the CPSU and built his career along Komsomol lines.

The lack of clear unified command played a cruel joke on Dudayev's men during the crisis in Dagestan. The “chemistry” between the two leaders was clearly lacking. Israpilov even complained about Raduyev's decisions in front of Russian TV cameras.

No Third Time

Behind the two commanders stood a sizable group for “ChRI” standards—250 volunteers: experienced, motivated, and well-equipped. According to eyewitness accounts, the Dudayevites in Pervomayskoye—unlike their opponents—had no problems with weapons, ammunition, equipment (even night vision devices), or communications. Throughout the raid, separatists routinely intercepted federal communications, while the federals themselves sometimes couldn't contact their own units if they belonged to different agencies.

The Russian side later attributed the enemy's combat effectiveness to the alleged presence of Middle Eastern militants rather than Chechens in Israpilov and Raduyev's group. That wasn't the case, though some Arab mercenaries did participate in the Dagestan raid. More interestingly, among them were former Russian soldiers who had switched sides to “ChRI.” Journalist Valery Yakov later recalled meeting a Russian conscript among the attackers in Kizlyar—he had converted to Islam as a POW and embraced separatist ideas. While waiting for the standoff to end, the defector sent a note to his family through Yakov, saying: “God willing, we'll meet again. For now, I will fight for the freedom and independence of Chechnya. Love you.”

This would happen a bit later, in Pervomayskoye. But what happened in Kizlyar? Early in the morning on January 9, the Dudayevites—who had secretly entered Dagestan in small groups the day before—attacked the city. The element of surprise was on their side, as Russian security services ignored warnings about the impending attack. But the militants also made mistakes: their intelligence gave them inaccurate data on federal forces in the city. As a result, Israpilov and Raduyev's units failed to capture the airfield, the Interior Troops garrison, and other targets, losing a couple dozen comrades. After failing against armed opponents, the attackers turned on the unarmed—repeating Basayev's crime in Budyonnovsk.

Here, the militants had no problems, especially as the city was in chaos after the sudden attack.

Taking advantage of the chaos, the separatists gathered at least 2,117 hostages in the city hospital on January 9. Those who tried to resist were shot on the spot.

Then, as in Budyonnovsk, the Dudayevites mined the building, invited journalists, and put forward political demands—the withdrawal of federal troops from Chechnya, a personal meeting between Yeltsin and Dudayev, and the annulment of election results Moscow had managed to hold in the controlled part of the republic.

Israpilov believed the separatists could wring significant concessions from the Kremlin and even outdo Basayev's summer success.

Indeed, nearly twice as many hostages were taken in Kizlyar as in Budyonnovsk; by this measure, the Dagestan terrorist attack remains the largest in Russian (and apparently world) history.

But Raduyev, though he played the role of a tough bandit for the cameras, was in no hurry to risk his life. By satellite phone, he described the situation to Dudayev, who gave the go-ahead for the squad to return to Chechnya without any political results: the shock content from Kizlyar on TV was already enough of a “ChRI” victory.

This line of thinking suited the Dagestan authorities. Regional head Magomedali Magomedov immediately entered negotiations with Raduyev, seeking the prompt departure of the uninvited guests from his republic. After some hesitation, the militants agreed, and the parties reached a consensus. The militants and Dagestanis agreed: the former would release the captured Kizlyar residents, while the latter would provide buses and ten local officials as a human shield. Together, they would travel to the Chechen-Dagestan border and part ways—just like the Budyonnovsk scenario.

But Russia's top leadership saw the situation differently. Their intense emotions and thoughts boiled down to this: Kizlyar is a second Budyonnovsk, and there will not be a third such terrorist attack.

Komsomol Member in Pervomayskoye

In the first hours after the tragedy, “hawkish” positions were taken in Moscow by Interior Minister Anatoly Kulikov and FSB chief Mikhail Barsukov. They were immediately supported by the commander of the federal group in Chechnya, General Vyacheslav Tikhomirov. The top security officials categorically rejected the idea of letting Raduyev and Israpilov's group return to “ChRI,” regardless of what the Dagestan authorities had promised them.

President Boris Yeltsin backed the “hawks.” In the winter of 1996, he decided to run for a second term, aware of his low popularity. The incumbent's rating barely exceeded 5%, and in December 1995, the pro-presidential bloc “Our Home—Russia” failed in the Duma elections with just over 10% of the vote. Yeltsin and his team understood the reasons for this electoral nightmare. In addition to all the socio-economic difficulties caused by the USSR's collapse, people were irritated that the Kremlin, having launched the Chechen campaign, clearly didn't know how to conduct it.

Army failures were discussed in prime time on federal channels, and the funeral of almost every dead soldier turned into an anti-war rally.

Video footage from January 1996 shows how angry Yeltsin was. He lashed out at his own security forces, denounced journalists, and hurled threats at Dudayev and his henchmen. But much of this anger stemmed from Boris Nikolayevich's frustration with himself. In the summer, during the Budyonnovsk crisis, the president distanced himself from the problem. Security services botched the storming of the hospital seized by militants, and Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, who took responsibility, allowed Basayev's group to leave in exchange for the hostages' release. In winter, Yeltsin made it clear—he wanted a forceful solution, not a deal.

“I believe that we cannot... A state with power, a state with strength, [should not] tolerate such groups on its territory. No! This must end! Journalists are also to blame: back then [in Budyonnovsk] the issue could have been resolved, but journalists made a fuss. As if the bandit suffers when he's wounded! There! They feel sorry for the bandits!”

—from Yeltsin's press approach in Moscow, January 15, 1996

On the morning of January 10, the bus convoy with militants and Dagestani officials left Kizlyar. At the last moment, Raduyev changed his mind about releasing all the “ordinary” hostages and kept about a hundred local residents as a precaution. Around 11:00, the convoy reached Pervomayskoye—a small village on the right bank of the Terek River, right at the border with Chechnya. There was a federal checkpoint manned by fewer than 40 police officers from the Novosibirsk region. The Siberians had been ordered in advance not to open fire on the unexpected guests.

Then the irreversible happened. Military helicopters caught up with the convoy and struck the bridge over the Terek. The structure immediately collapsed, and Raduyev's unit lost its escape route to “ChRI.” The separatists realized they were trapped and would soon be attacked on the ground (in fact, special forces—due to poor coordination among Russian security agencies—arrived an hour or two after the bridge collapsed). The Dudayevites then seized the checkpoint and disarmed the disoriented police. The former Komsomol leader's men occupied Pervomayskoye, from which nearly all local residents fled in panic.

The situation took a strange turn. Russian security forces achieved the withdrawal of militants from Kizlyar but inadvertently gave them a new potential defense point. The enemy was now right on the border of their territory but cut off from “ChRI” by the cold waters of the Terek. However, a week later, Raduyev and Israpilov found a solution to the river puzzle.

Fire, Water, and a Pipe

Yeltsin appointed FSB chief Barsukov to head the Dagestan operation. Everyone saw this as another signal that the president wanted a military victory. Barsukov's predecessor, Sergei Stepashin, had lost his position precisely for failing to organize a competent operation in Budyonnovsk.

Barsukov himself had no objections to “cleansing” Pervomayskoye. The operation's chief of staff, General Dmitry Gerasimov, felt differently. Unlike his boss, who had made his career in the Kremlin commandant's office, Gerasimov was a true special forces officer, a veteran of the Soviet GRU and the Afghan intervention. He was skeptical about storming a village with dozens of hostages and reasonably suggested luring the militants out of Pervomayskoye and attacking them again on the road.

But there was another problem—after the bridge over the Terek was destroyed, Raduyev and Israpilov no longer trusted Russian representatives. Now they demanded official guarantees and the arrival of top federal politicians in Pervomayskoye. Barsukov's headquarters could not agree to this—the “cleansing” of the village could only be prevented by the enemy's unconditional surrender, which was unacceptable to “ChRI” militants. It was a vicious circle.

Over several days, the federals amassed a force of 2,000–2,500 troops from the Interior Ministry, FSB, and Russian Armed Forces around Pervomayskoye. This was a highly diverse force, including FSB special unit “Alpha,” similar Interior Troops units, SOBR officers from various regions, and, inevitably, conscripted motorized riflemen and artillerymen. These units had very different levels and standards of training. In addition, the combined force had to go without proper food and warm shelter during the standoff: soldiers slept in holes and hunted cows fleeing the village. By the climax of the crisis, many security officers were barely standing from hunger, exhaustion, and cold.

On January 14, Raduyev finally rejected the surrender ultimatum from Barsukov, who had arrived at the scene. On January 15, the federals attacked the Dudayevites from several directions, citing allegations that the militants had executed some hostages and certain Dagestani elders who had supposedly come to reason with the fanatics. The fighting lasted all day, claimed dozens of lives on both sides, and brought no success to the security forces. “ChRI” militants retained control of the village center, where most hostages were held.

“They [the special forces] could barely walk anymore—wet, frozen, hungry. Sick with fever. Tomorrow morning, they'll have to storm again with fevers, hungry, and without enough fire support.”

—Pavel Golubets, Internal Troops general, commander of the assault on Pervomayskoye

The same thing happened on the 16th and 17th of January. The federals acted too disjointedly, while their opponents had managed—using captive police from the checkpoint—to fortify themselves well in Pervomayskoye during the standoff. Out of desperation, the besiegers increasingly fired blindly at the village: with unguided rockets from helicopters and Grad rocket systems from the ground. FSB press secretary Alexander Mikhailov told journalists on site that “the air force is working with surgical precision, not a single object with hostages has been hit,” and that there was no threat to the hostages—the terrorists “practically have none left.”

It seemed that in another day or two, nothing would remain of Raduyev and Israpilov's group. The militant Israpilov suggested placing the remaining hostages around the perimeter of the half-ruined village and making a last stand. But the less suicidal Raduyev proposed a new route to Chechnya—via a gas pipeline running over the Terek next to Pervomayskoye. The structure was wide enough for the retreating militants to use it as a bridge rather than crawl inside, risking their lives. Crucially, federal forces' cordon was weakest at the Terek—either the besiegers didn't know about the pipeline or underestimated its potential.

In any case, on the night of January 18, the Dudayevites broke through enemy defenses in fierce hand-to-hand combat and headed to the pipeline, taking some hostages with them. “ChRI” did not achieve an unambiguous victory. Nearly the entire vanguard of the group was killed during the breakout, and then Russian helicopters struck the militants as they crossed the pipeline. Dozens more militants died, and the survivors on the western, Chechen bank of the Terek had to scatter in all directions.

A few days later, FSB director Mikhail Barsukov explained the partial success of the enemy's escape at a press conference by their unusual tactic— “the militants took off their boots and crossed barefoot.” The chief security officer put himself in a ridiculous position. Even Russians far removed from security agencies understood that the boots from the militants' corpses—shown to Barsukov by his subordinates—had been taken by chronically under-equipped Russian soldiers. Either Mikhail Ivanovich believed an obvious lie or thought the public would swallow it. The notoriously outspoken 1990s journalist Alexander Minkin summed it up: “If the Federal Security Service is in the hands of such a man, there's no doubt—the country is in danger.”

White and Black Swans

The Kizlyar and Pervomayskoye crisis was extraordinarily bloody by the standards of the First Chechen War. There is still no universally accepted casualty count, but it is certain that the number runs into the hundreds on both sides.

During the militants' attack on the city alone, 34 local residents died, including law enforcement personnel. During the “cleansing” of Pervomayskoye, another 23 to 26 federals were killed. Under various circumstances, at least thirteen hostages did not survive until the morning of January 18—some were indeed killed by the captors, but many were likely killed by the fire of their would-be rescuers. Many dozens of civilians and security personnel were wounded to varying degrees.

Irrecoverable losses for “ChRI” are estimated at about a hundred fighters. In other words, about half of Raduyev and Israpilov's original group died—an unacceptably high number for the self-proclaimed republic, especially given the political senselessness of the raid. Unlike Basayev in the summer of 1995, Raduyev in the winter of 1996 brought home no agreement or deal with the enemy. Many in “ChRI” were outraged by the results of the raid for other reasons as well. During the breakout from Pervomayskoye, Israpilov and Raduyev left dozens of their comrades' bodies and at least 20 prisoners behind. By mountain tradition, such disgrace is unforgivable for a commander. In exchange for the dead and captured, the separatists had to release all remaining hostages.

Both field commanders nevertheless remained prominent figures in the political life of the unrecognized republic, but neither survived the Second Chechen War. On February 1, 2000, Israpilov was killed in a new battle for Grozny. A month later, pro-Russian Chechens handed Raduyev over to the federals—Salman was sentenced to life in prison by a Russian court. On December 14, 2002, the Komsomol leader-turned-terrorist died under unclear circumstances in the infamous “White Swan” prison.

Their adversaries in Kizlyar and Pervomayskoye had less dramatic fates. However, after the Dagestan crisis, the careers of key security officials from Yeltsin's team began to decline. In June of that same 1996, Barsukov lost his position as FSB chief. Against the backdrop of the presidential campaign, the security director got involved in intrigues within Yeltsin's circle and fell victim to the notorious “Xerox box” scandal. Interior Minister Kulikov stayed out of backroom games and remained in office until the “default” of 1998, when he had to leave with Chernomyrdin's entire government. Only former United Group commander Vyacheslav Tikhomirov remained influential into the 2000s—he was forced to resign only in 2005.

The double terrorist attack in Dagestan left Russian society with mixed feelings. On the one hand, it once again showed the ineffectiveness of command in the Caucasus and highlighted the dire situation of ordinary soldiers and police. At the same time, a nation increasingly suffering from a Weimar syndrome could not help but feel a fleeting pride that the authorities no longer negotiated with terrorists but tried to destroy them. Not coincidentally, from January 1996, Yeltsin's approval rating among Russians began to rise steadily. Russian military personnel also warmed to the government.

“No matter how hard the militants tried, they couldn't repeat Budyonnovsk. By the way, after Pervomayskoye, militants never again dared such large-scale raids.”

—Gennady Troshev, Russian Army general, 2001

In retrospect, the Pervomayskoye operation looks like a watershed for all post-Soviet Russian history. It was then that the authorities first—albeit very timidly, almost surgically—constructed an alternative narrative of events for TV viewers, and the public, though irritated, accepted it. The country's leadership also truly realized a crucial, if unpleasant, truth: in a crisis, the silent majority is more likely to accept the “collateral” deaths of fellow citizens than tolerate a public display of weakness toward the enemy. The Kremlin's adherence to this lesson was evident during the “Nord-Ost” siege, the Beslan school takeover, and, as we see now, in the war against Ukraine approaching its fourth year.

Main sources for this article:

Zygar M. “Everyone is Free: The Story of How Elections Ended in Russia in 1996”;

Kaluga E. “Kizlyar and Pervomayskoye. January 1996”;

Kozlov S. “GRU Special Forces. Fifty Years of History, Twenty Years of War”

Leonov M. “The Hostage-Taking and So Many Victims Could Have Been Avoided”

Project “Minute by Minute.” “2,000 Hostages”

Project “Indigenous Workers' Council.” “Kizlyar and Pervomayskoye. How Raduyev Lost Face Twice”