Support the author!

«I can’t return to Russia. But staying in the US is also unsafe»

After Donald Trump returned to power, many Russian political emigrants found themselves facing the threat of deportation from the US. In the summer of 2025, one of them, Leonid Melekhin, was denied political asylum and deported to Perm, where he was detained right at the airport. For six months now, he has been awaiting trial in a local pre-trial detention center on criminal charges of justifying terrorism. Under Russian law, Melekhin faces two to five years in prison. To prevent more cases like this, “Most.Media” launched a petition to the US authorities in late July, which has been signed by more than 31,000 people. Among them are many political activists who, if deported from the US, face repression in Russia. We are beginning to publish their stories.

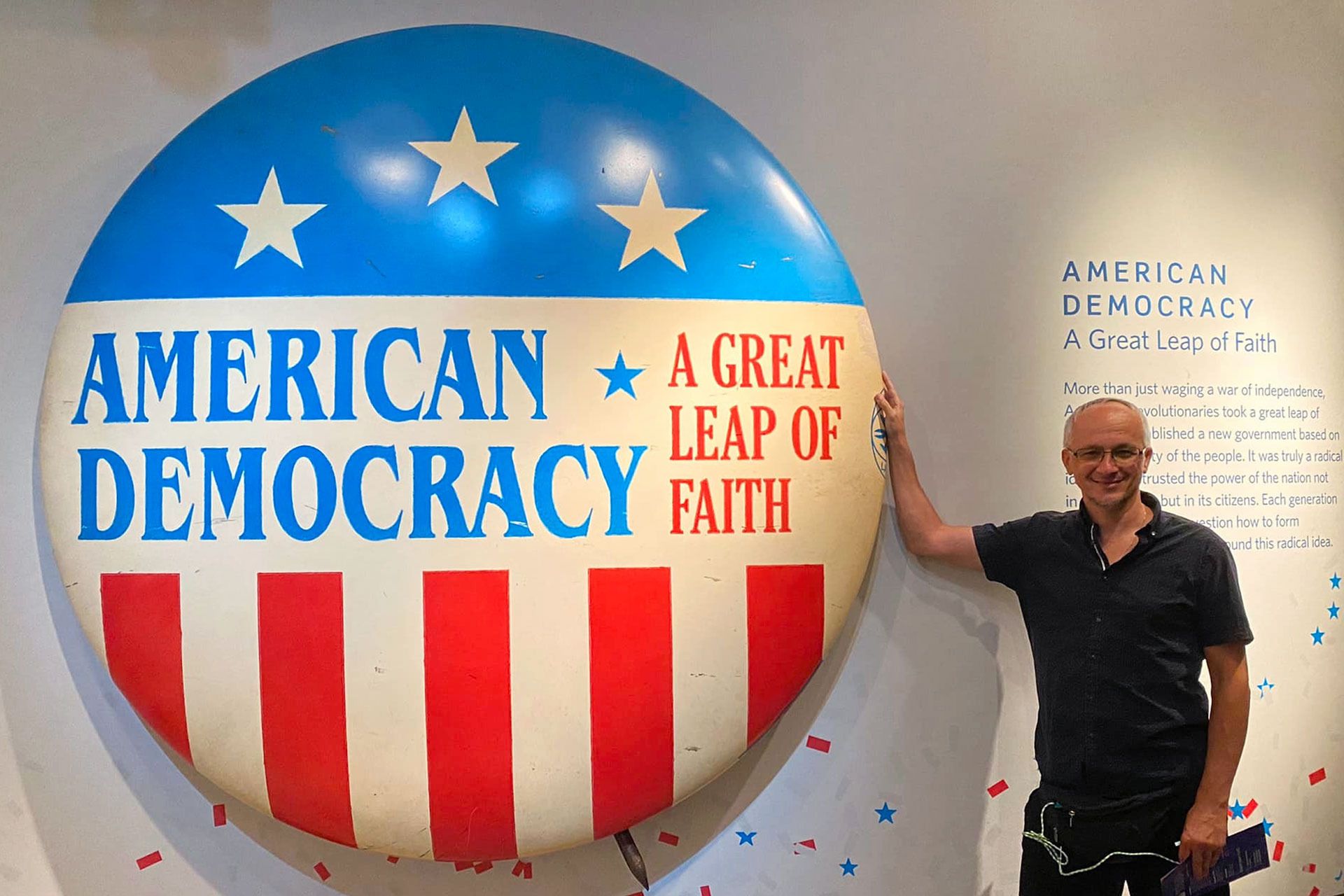

“My ‘American dream’ turned into a nomadic lifestyle. I travel across all the states in a huge truck. My work schedule: about a month on the road and three days at home,” says Russian civil activist Eduard Glezin, who became a long-haul truck driver in the US. “The downsides: 14-hour workdays and being far from home. The upsides: the chance to see America, even if only through the truck window.” However, in recent months, Glezin anxiously watches for ICE immigration police raids from his truck window, because his name is on the deportation list.

Glezin ended up facing deportation from the US after 10 years of waiting for political asylum. He left for America in 2014 to avoid Russian prison because of his political stance. Now, an American immigration court may send him back to Russia.

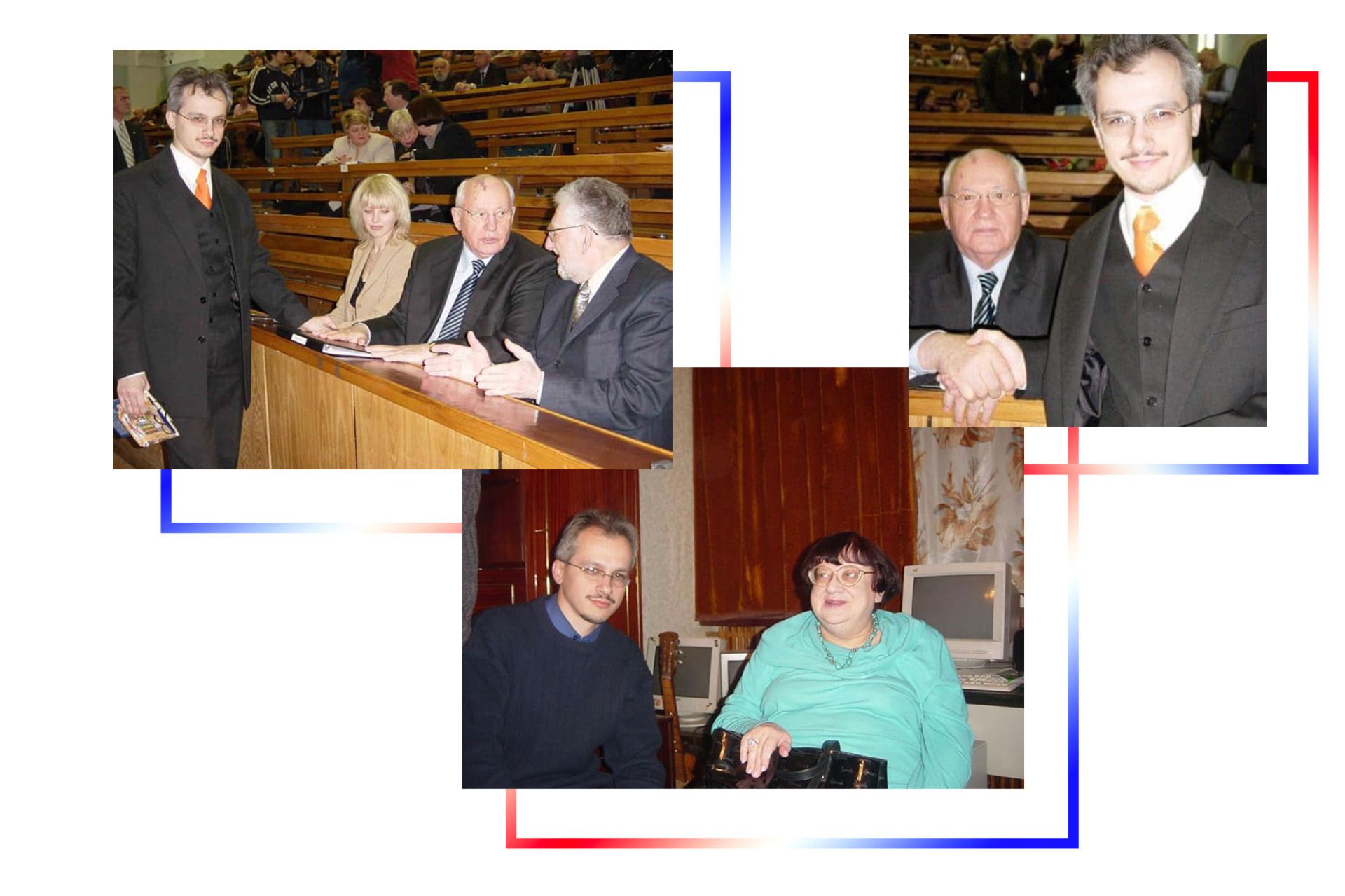

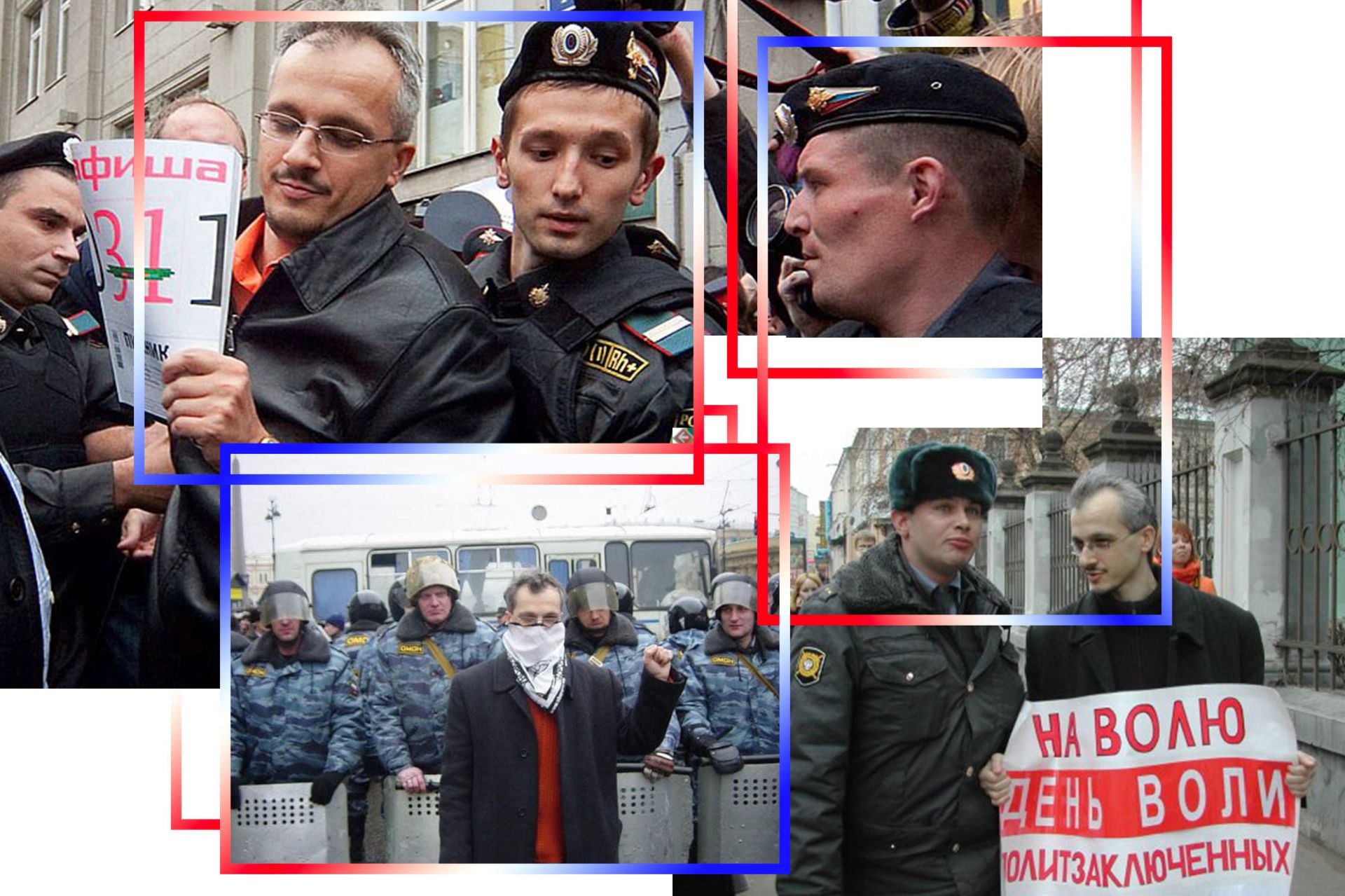

Before emigrating, Glezin lived in Moscow, worked in the press office of the Russian Federation’s Commissioner for Human Rights, and was a coordinator of the democratic movement “Oborona.” He regularly participated in protest rallies, during which he was detained by the police a total of 15 times.

Detentions at rallies didn’t interfere with Glezin’s work as long as Vladimir Lukin was the Commissioner for Human Rights—they both belonged to the same democratic camp. Lukin, for example, was one of the three co-founders of the Yabloko party and publicly defended protesters.

In 2014, Lukin resigned, and the State Duma appointed Ella Pamfilova, who was more loyal to Putin, in his place. “For me, this ended with the head of HR, a former FSB officer, showing me a folder with compromising materials and telling me he was handing it over to the FSB,” says Glezin. According to him, the HR manager threatened to initiate a criminal case for public calls to extremist activity—at the time, this charge could mean up to five years in prison. After that, Eduard was fired from the ombudsman’s office. Because of threats to his life and safety, he left for the US, where he applied for political asylum.

For 10 years, Glezin waited to be called for an interview with an immigration officer to prove the facts of political persecution in Russia. In the end, due to the officer’s bias, his and his wife’s asylum applications were rejected. “Technically, I’m already in the deportation process,” he clarifies. A hearing on his case is scheduled for June 22, 2026, with a judge who, statistically, denies 90% of cases.

Since 2014, Eduard has been in the US legally, with a tax number and work permit. For the past five years, the former human rights press officer has worked as a truck driver in Florida. “But now I could lose my job, because under new regulations, only US citizens or green card holders can drive big trucks,” he says. And if he loses his only source of income, Glezin won’t be able to pay his lawyer.

The situation is made worse by the fact that Eduard and his wife Svetlana are already on ICE’s deportation lists. Any work trip could end in arrest during an immigration police raid. In that case, the couple will be sent to immigration detention (detention center) to await trial and likely deportation, separately. This will double their legal expenses, which in the US are not cheap: legal support for one case now costs about $20,000.

In the more than 10 years Glezin has waited for a decision on his asylum application, political repression in Russia has become harsher. “Now, I face prosecution at home under six articles of the Criminal Code, including treason, which can mean a life sentence,” says Eduard. All these years, he has not hidden his critical stance toward the Russian authorities, and they can easily gather evidence from his social media.

According to him, waiting over 10 years for political asylum in America is not unusually long: “Actually, this is typical not only for Florida, but for the US in general.” “Many asylum seekers were retroactively declared criminals. ICE is literally hunting people. This happens both in big cities and on the roads. You can be arrested during an asylum interview, or in a grocery store—anywhere,” he lists.

Theoretically, it is possible to self-deport from the US to a third country, but that also depends on the immigration court’s decision. “I have to provide them with a bank statement and coordinate my departure route—they might not approve it and still deport me to Russia. There have been such cases,” says the activist. — I can't return to Russia. But staying in the US is also unsafe.“

***

You can join the open letter “Most.Media“ against the deportation of Russian political activists from the US to Russia here.