Support the author!

160 years ago the South lost the Civil War in the USA. What would the world be like if they had won?

The Civil War in the USA is a significant watershed not only for America's past but for the entire world. This conflict was the last war of the Modern Era and the first of contemporary history. It began with volunteer militias whose commanders emulated Frederick the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte, and ended with mass professional armies fully prepared for the meat grinders of World War I. Ironclads, submarines, repeating firearms, field trenches, and the telegraph—all were first used in the war of 1861–1865. The political consequences of the American conflict were no less important.

“Any understanding of our nation must be based on studying the Civil War. It defined us. The Revolution contributed its part. Our involvement in European wars, starting with World War I, also played a role. But it was the Civil War that made us who we are, defining both our strengths and flaws. And if you want to grasp the American character, you need to study the great catastrophe of the mid-19th century,” wrote American historian Shelby Foote.

An alternative outcome of the conflict—the victory of the Southern Confederacy over the government in Washington—would have changed the history of the entire planet. Alaska might have remained Russian forever, and perhaps another state in the Americas would have grown into the world's leading economy. The United States themselves might have permanently fractured by the end of the 19th century. On the 160th anniversary of the end of the American civil strife, we offer some reflections on what happened and what might have been.

One victory—and several surrenders at once

The American Civil War is an event with a well-known starting point. On April 12, 1861, in South Carolina, rebels shelled the island fort of Sumter, whose garrison had sworn allegiance to the federal government and refused to surrender the fortress to the self-proclaimed Confederate States of America (CSA) on the mainland. President Abraham Lincoln's administration used the incident as a pretext for a military campaign against the separatists.

However, as often happened in world history, the planned pinpoint operation turned into a multiyear bloody slaughter. A slaughter that cost the States over 600,000 lives (more than the USA later lost in both World Wars, Vietnam, and Iraq combined) and whose definitive end is hard to determine. American tradition places special importance on April 9, Appomattox Day. On this day in 1865, in the town of the same name in Virginia, the Army of Northern Virginia under General Robert E. Lee, the key force of the Confederate troops, surrendered.

By spring 1865, the South's strategic position was dire. The rebels controlled less than half of the claimed territory, which was split in two by enemy forces. But the tireless Lee initially refused to surrender without a fight. In early April, his troops abandoned the CSA capital Richmond and retreated deeper into friendly territory. The Southern command hoped to replenish supplies there and continue resistance.

However, the enemy was unwilling to give the Confederates any chance. On April 6, 1865, Union General Philip Sheridan caught the retreating Southerners near Appomattox, and a day later, two US armies united there. On April 9, Lee's staff attempted a counterattack but immediately revealed a glaring disparity in forces. The famed commander was forced to accept the offer of his counterpart, Federal Commander Ulysses Grant, for unconditional surrender.

“I have nothing left to do but to meet General Grant, though I would rather die a thousand deaths.”

- Robert E. Lee before surrender at Appomattox

That evening, over 28,000 soldiers and officers of the Army of Northern Virginia laid down their arms. The victors fed the defeated and sent them home on their word not to take up arms against the US government again. Here, one historical curiosity must be mentioned. The surrender documents at Appomattox were signed by Lee and Grant in the home of local grocer William McLean, where the Southerners had their headquarters.

The mentioned businessman had previously lived in another Virginian town, Bull Run. There, in July 1861, he witnessed the first major battle of the Civil War. The Confederates then also chose McLean’s mansion for their headquarters. The house was heavily damaged by federal artillery, after which the grocer decided to move to a quieter place in Appomattox. There he witnessed the war’s end, giving rise to a common joke among American historians: the war started in Bill McLean’s backyard and ended in his living room. But let’s return from the unlucky grocer to the soldiers in gray uniforms.

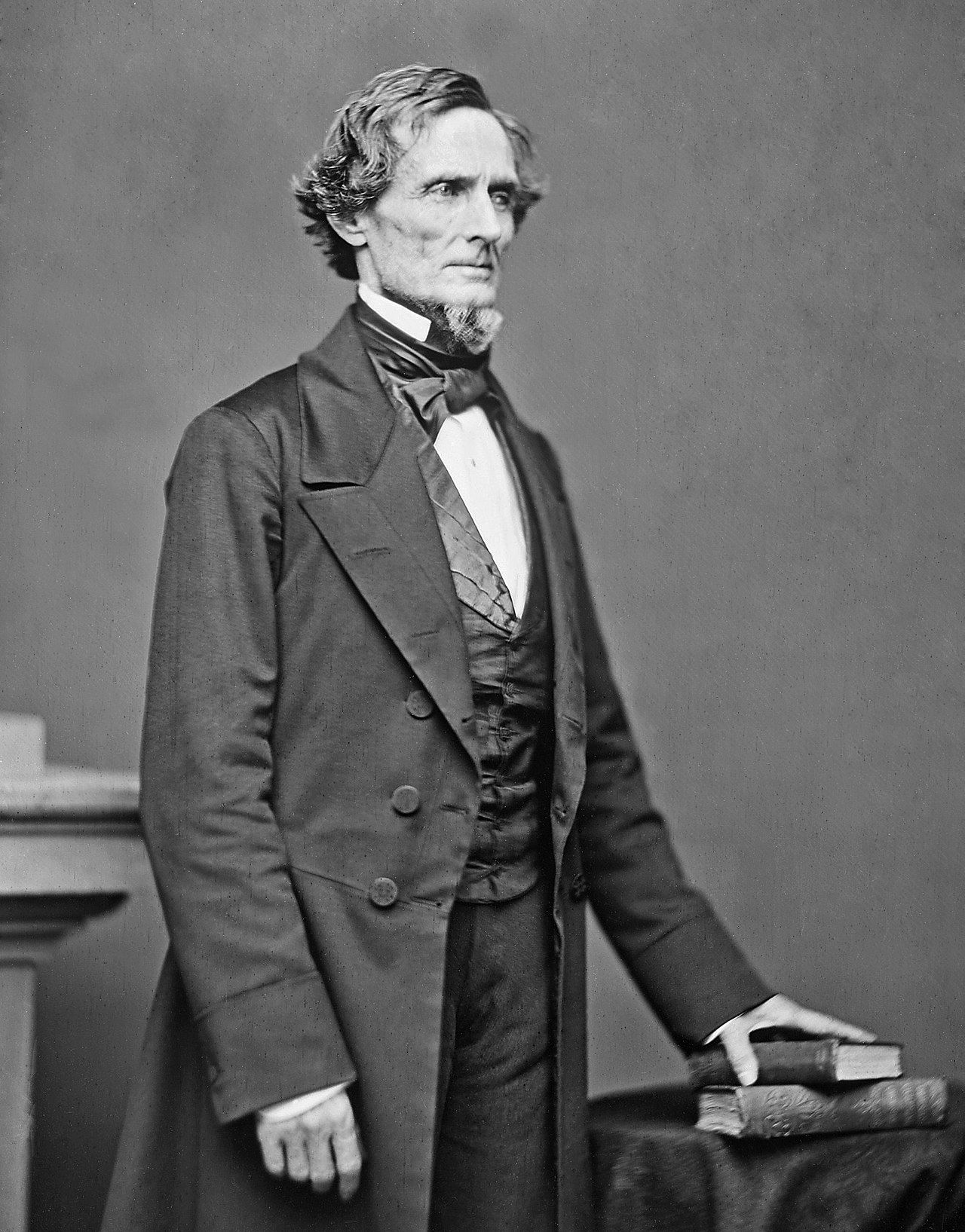

Formally, Lee’s surrender did not mean the capitulation of all rebel forces. However, in other Southern armies, the gray-bearded general’s decision was seen as a precedent, despite calls from CSA President Jefferson Davis to fight to the end. On April 26, 1865, a 50,000-strong group under General Joseph Johnston surrendered in North Carolina. On May 26, a 20,000-strong army of the Trans-Mississippi District under General Kirby Smith followed suit in Texas. The soldiers of this unit were the last Confederates still technically capable of engaging in frontal combat with the Federals. Therefore, most historians in the 21st century consider May 26 the de facto end date of the war.

Why de facto? Because in reality, the surrender of small garrisons, partisan units, naval crews, and Indian allies of the CSA dragged on until November 1865. Legally, the war ended only on August 20, 1866. On that day, President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s tragic successor, declared: “The mentioned rebellion is ended and peace, order, tranquility, and civil authority now exist throughout the United States of America.” But what had shattered that very order five years before Johnson’s proclamation?

A war over slavery, but not against it

It is tempting to reduce the causes of the American Civil War to a simple model. For example, to put slavery at the forefront: the North had no slaves, while in the South they formed the economic foundation. This shameful institution hindered the development of all states and tarnished their Union’s global image. But Southerners were unwilling to free slaves voluntarily, so the central government had to resort to force.

Conversely, one could reduce the conflict to defending local identity. Claiming that Lincoln’s 1861 administration’s policies opposed not only slavery but the entire Southern distinctiveness. The threat of destruction loomed over a local culture built around plantation agriculture. Thus, the Southerners peacefully separated into a separate Confederacy, and only Washington’s aggression forced them to take up arms.

In reality, the truth lies somewhere in between. Initially, President Lincoln and his team did not seek the destruction of slavery per se. The Republican Party’s 1860 platform did not call for the emancipation of black people. It only demanded the enforcement of the ban on the African slave trade (introduced back in 1808) and the prevention of slavery in new western states.

The famous presidential Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863—i.e., a year and a half after the war began. However, a special clause in the document stipulated that slaveholders in territories controlled by Washington were not affected by this measure. It is quite likely that had Lincoln not been assassinated on April 14, 1865, he would have chosen a much milder path to abolishing slavery than his successors did.

“I have no intention, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I intend not to do so.”

- Abraham Lincoln, inaugural address, March 4, 1861

On the other hand, slavery in Dixie (as the Southern states were collectively called then) was impossible to contain within existing limits. The nature of plantation agriculture required constant expansion of lands. Moreover, the local elite had no desire to confine themselves within their borders. In the 1840s and 1850s, Southern elites persistently lobbied for three federal measures unacceptable to Northern states:

- Legality of slavery in new states created as the USA expanded westward to the Pacific. This ambition discouraged poor Northerners from moving west in search of a better life;

- Recognition of slavery throughout the Union, including states that had abolished it long before the mid-19th century. Northerners were required to extradite fugitive blacks to the South and refrain from any criticism of slavery;

- Abolition of protective tariffs on European manufactured goods. Southerners wanted to trade directly with Europe, caring little about the young industry in other US regions.

It seemed the economic balance favored Dixie. Northern industry was barely getting on its feet—big money was made by the Southern states. Before the war, the future CSA accounted for more than two-thirds of American exports, primarily due to cotton picked by black slaves. Planters also held the key political power of the time—the Democratic Party.

Yes, administrations in Washington changed every four years, but successive White House occupants always listened to voices from Charleston, New Orleans, or Atlanta. Everything began to change in 1854, when a group of reformers disillusioned with the old order formed the new Republican Party in Ripon, Wisconsin. The new party’s agenda directly challenged Southern interests: it declared that Union rights were more important than states’ liberties and that there should be no slavery in the West.

Initially, Southerners mocked the Republicans in their newspapers as a “gathering of greasy artisans, dirty mechanics, and small farmers,“ but by the late 1850s, the Republicans had become the second party in the USA. On November 6, 1860, their candidate Abraham Lincoln decisively won the presidential election (180 of 303 electoral votes). Much of the Illinois native’s success came from divisions among his opponents: three candidates defending slaveholders’ rights split the vote. After the loss, Dixie concluded it no longer needed the Union with its Northern-dominated administration in Washington.

In winter 1861, seven states of the so-called “Deep South”—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—declared secession. On February 4, their representatives proclaimed a new Confederacy. After the April 12, 1861 events and the war’s actual start, four more states joined the CSA (Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee). Missouri and Kentucky tried to secede but were preemptively occupied by federal troops in fall 1861.

Arrogant South versus cunning North

In retrospect, the Southern rebellion against the federal government looks like a sophisticated suicide: the military resources of the two sides were too unequal. To start with, the CSA had nearly half the population of the Union-loyal states: 9.1 million versus 22.1 million. Moreover, a third of those nine million were black—dangerous in the rear and fundamentally unacceptable on the front lines armed.

The Confederacy hopelessly lagged behind the USA in all other crucial war metrics. Ten times less industrial output, four times less wheat harvested, two and a half times shorter railroads… No wonder that during 1861–1865, Southern soldiers regularly marched barefoot in homemade uniforms and often “bought” food from Northern enemies. Between battles, Confederates secretly traded tobacco—a rare commodity that did not become scarce in the South after the Sumter bombardment.

“The last few years I spent in the North. And I saw many things none of you ever saw. I saw thousands of immigrants ready to fight for the Yankees for a piece of bread and a few dollars. I saw factories, shipyards, mines, and coal pits—everything we lack. And we have only cotton, slaves, and arrogance. It’s not us who will defeat them, but they will defeat us in a month.“

- Rhett Butler’s monologue from “Gone with the Wind”

The literary character seriously underestimated the factor of “arrogance”—in other words, the specific Southern mentality. Here lay the main (if not the only) advantage of Dixie over the enemy. Less than a quarter of white families owned slaves in the South. Large planters owning 20 or more slaves made up about 1% of that group. But all their neighbors—from craftsmen and small farmers to journalists and lawyers—thought like their oligarchs: cotton is our breadwinner, slavery is the foundation of normal life, and anyone who disagrees is a mortal enemy.

By the late 1850s, Southern politicians and journalists had pumped their compatriots with toxic propaganda. Contrary to facts, they claimed that a Republican victory in the presidential election would be a mortal threat to good old Dixie. Terrifyingly, the brazen “Yankees” would declare “Negroes” equal to whites and confiscate private property from rightful owners! The only way to stop this madness was secession, even if protecting their new state required war.

These narratives sharply contrasted with the tone of Northern press. There, in the same years, discussions focused on how to avoid the Union’s collapse and find a compromise with restless neighbors. Many newspapers directly accused Republicans of provoking Southerners to bloodshed.

It is no surprise that the prolongation of the conflict was perceived differently by ordinary people in the CSA and the USA: the former with stoicism, the latter with clear indignation. Desertions in Union armies numbered in the tens of thousands, and their rear was shaken by the “Copperhead” faction of the Northern Democratic Party. Opponents of Lincoln demanded the immediate resignation of the “usurper” and an end to the “Negro war.”

The faction members preferred to call themselves “Peace Democrats.” They were dubbed “Copperheads” by supporters of the president after a poisonous snake of the same name, creating something like the Russian idiom “snake in the grass.”

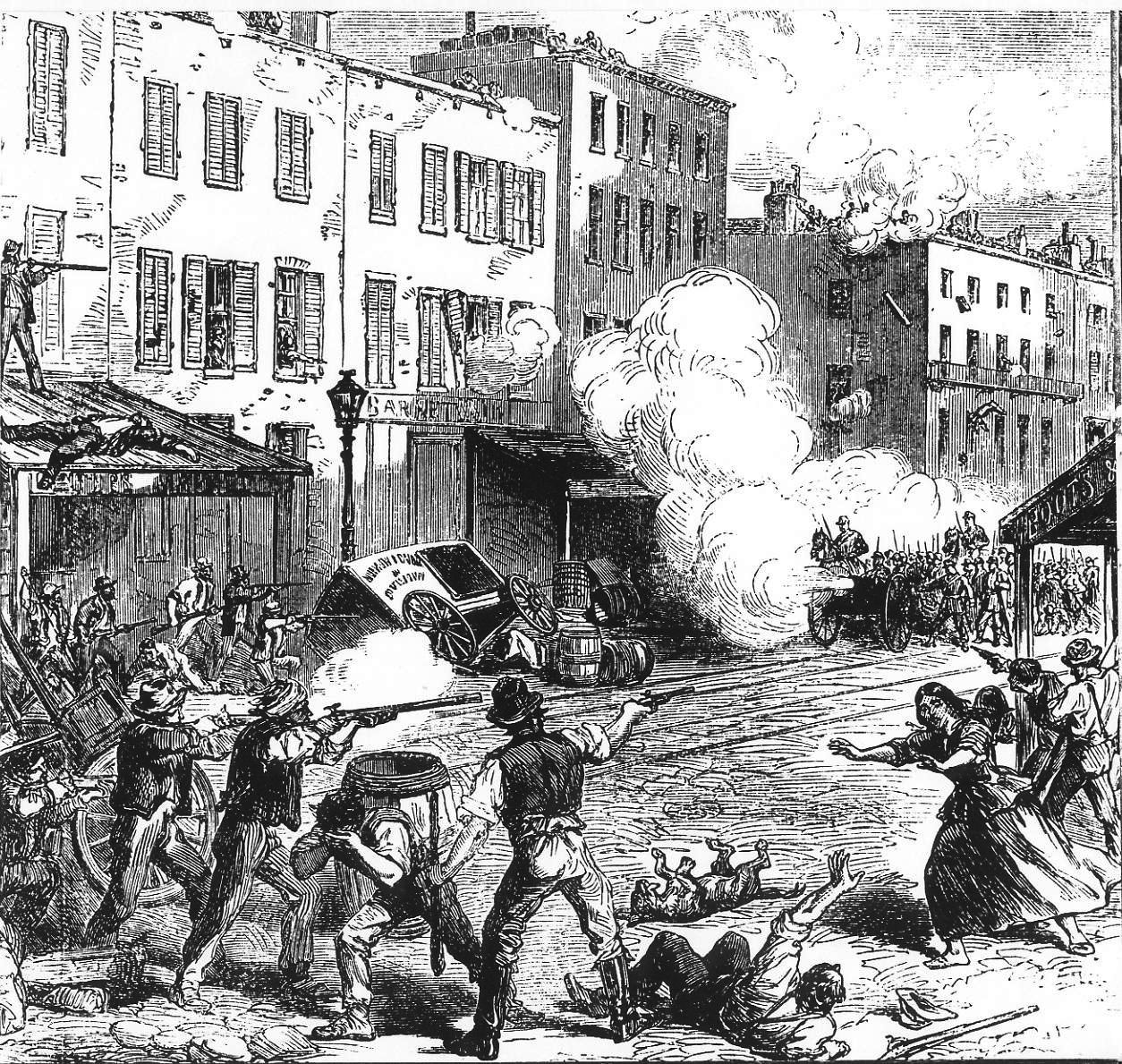

It is telling that the largest draft riot in the USA—in New York in mid-July 1863—occurred just a week after two pivotal victories by allied armies. On July 3, General George Meade’s Potomac Army defeated the rebels at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and on July 4, General Grant’s Tennessee Army captured the vital fortress of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Within two days, the Northerners forced the Southerners to flee their territory and split the Confederacy in two.

The rioters in New York could not have been unaware of these victories—the telegraph reliably brought front-line news to city residents. It’s just that too many people there under any circumstances did not want to wear blue uniforms. By the way, early in the war, New York elites openly discussed leaving the USA to then join the Confederates as a free city. The conspirators lacked the spirit for such an adventure, but their city never became a reliable rear for the warring army.

How enemies helped Lincoln win the election

But could Southern solidarity have translated into military-political victory? Under certain circumstances—yes.

It should be noted that the American war, due to its complicated course (about 10,000 clashes), is rich in episodes that, many years later, can be presented as decisive. Had a certain rebel division arrived in time to aid surrounded comrades, or had a certain CSA commander led his men not to the right but to the left of enemy positions, perhaps General Lee would have been the one accepting Grant’s surrender.

The start of this intriguing game was set personally by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. During the war, he claimed it could have ended in a few months. After the first major battle at Bull Run on July 21, 1861, his generals Joseph Johnston and Pierre Beauregard should have finished off the “Yankees.” But instead of a swift march on Washington, just 30 miles (about 50 kilometers) away, a couple of negligent commanders chose to rest in their camps.

However, contemporaries immediately accused Davis of boasting. Johnston’s and Beauregard’s troops needed rest after Bull Run, and Washington was still guarded by a strong garrison. Moreover, capturing the enemy capital did not automatically mean the Federals’ surrender and recognition of CSA independence. Lincoln’s team would have suffered a significant defeat but could have continued the war from Boston or Philadelphia.

Equally speculative is the claim that the war’s course could have been reversed by Lee’s victory at the aforementioned Gettysburg in July 1863. It is often asserted that such a triumph would have led Britain and France, secretly aiding the Confederates, to officially recognize them. Allegedly, Europeans would have sent not only diplomats but expeditionary forces, ending the war like the Crimean conflict eight years earlier. But in reality, there is no evidence for this.

The bloody experience of the Crimean campaign made Paris and London more cautious about overseas “special operations.” Moreover, the Confederates’ image was severely damaged by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

From freedom fighters for their homeland, the Southerners became defenders of slavery in foreign eyes, and this institution was much disliked in mid-19th-century Europe; Lincoln issued the fateful document with this calculation. Finally, it’s unclear why the British and French would have been so impressed by Lee’s victory at Gettysburg, an unremarkable farming village—by then, the Virginian had already fiercely beaten the Northerners in many places across the American map.

Paradoxically, politically, the CSA could have won the conflict in summer-autumn 1864, when militarily they had no strong cards left. The fact is that Northern society then again slid into anti-war sentiments: last year’s victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg brought no immediate results. Federal troops wasted month after month in futile “meat assaults” on two key Southern cities, Richmond and Atlanta. Nothing good happened in the rear either: only taxes, inflation, and crime grew.

Against this backdrop, the Republicans’ idea to bring Lincoln to a second term in November 1864 seemed a hopeless adventure. At that time, Americans generally disliked reelecting incumbents—the last such precedent dated back to 1832. Observers believed that if the “Copperhead” Democrats fielded a convincing candidate, he would easily defeat the incumbent and then conclude an “honorable peace” with the CSA.

However, Lincoln was saved by his own enemies in a hopeless situation. In July 1864, Southern President Davis considered his troops’ actions in Atlanta too passive and appointed his confidant John Hood as the new commander there. The reckless general, eager to justify his patron’s trust, launched a counteroffensive. The ill-conceived operation failed spectacularly, and on September 2, the disgraced Hood surrendered Atlanta to the enemy.

Lincoln’s team rejoiced: finally, a major victory just two months before the historic vote. In the CSA, news from Georgia was rightly seen as the beginning of the end.

“Is it not cruel that the struggle of millions, sacrificing their lives, should end in nothing, should end in the ruin of all of us to indulge the petty whims and antipathies of one man [President Davis]?”

- Southern newspaper Richmond Examiner after Atlanta’s surrender

At the same time, the “Copperheads” also helped the White House. In August 1864, the Democratic Party adopted a sharply racist and openly pro-Confederate platform ahead of the elections. But the opposition nominated an unsuitable candidate—General George McClellan. A personal enemy of Lincoln, the officer openly supported restoring the United States.

McClellan failed to convince the protest audience and suffered a crushing defeat on November 8: 21–212 electoral votes in favor of Lincoln. Only six months remained until the surrenders of Lee, Johnston, and Kirby Smith.

Alaska ours, States divided, and Brazil a superpower?

And yet: what if? At the moment of truth, the Confederates only needed to avoid major mistakes and prolong the fighting for six months to a year. After all, Lincoln himself, during the tough summer of 1864, did not rule out compromises with the South and even secretly sent emissaries to the proud Davis (who set as a precondition the full release of the CSA’s claimed territory).

Suppose a black swan had arrived in America in 1864. Either Davis had the sense not to touch Atlanta, or Lincoln was ousted by opponents within the Republican Party, or General Lee performed another miracle and pushed the Northerners away from Richmond. In any case, Washington would have recognized the Confederacy’s existence—even if in reduced borders.

In such a virtual reality, the 1870s and 1880s would have been clearly better for the American South (or more precisely, for its white inhabitants) than in known history. Former rebels would not have experienced the hardships of the radical Republican Reconstruction, decades of economic depression, and cultural shock from federally enshrined racial equality. Yes, some time would have been needed to heal wounds: cotton production alone shrank fivefold in the Confederacy during the war. But the Confederates could have balanced things out with a clever annexation—perhaps by seizing Cuba from declining Spain; this idea was discussed in the South as early as the 1850s.

However, it is unlikely that the victorious CSA would have become a truly formidable empire that later subdued both Northern states and Central American countries.

For such triumphs, Southerners would have had to abandon their fragile confederate structure and industrialize. But both ideas seemed outrageous heresy to arrogant planters. So by the late 19th century, the Confederacy, amid falling global cotton prices, would have firmly fallen into stagnation—unless new elites emerged there, eager for fundamental reforms (especially abolition).

Things would not have gone much better in the North. After the inglorious war defeat, Lincoln’s successors (physically alive but politically dead) would have felt tied hand and foot. Most likely, they would not have bought Alaska from the Russian Empire. The 1867 deal met disapproval even in real history. After a lost war, no American politician would have risked such folly—trying to “replace” lost Southern fields with a cold Arctic peninsula. Alaska would have remained Russian, and the Klondike’s gold veins might have been discovered by imperial geologists suddenly sent to the distant land.

Meanwhile, the “Yankees” would have lost Dixie as a reliable supplier of raw materials and a market for their industrial products. So no Gilded Age, the foundation of a future superpower, would have occurred in this timeline. Postwar United States would likely have been shaken politically: old parties and federal bodies losing trust, workers fully embracing trendy Marxism and anarchism. State authorities, in any dispute with Washington, would have kept the February 4, 1861 precedent in mind. It is possible that by 1900, sovereign California, Vermont, or Utah would have appeared on the political map, and the “rump” USA would have shrunk to New England.

Northern and Southern heirs of the once United States would barely live in peace. Whatever terms Richmond’s and Washington’s envoys agreed on a “divorce” in 1864, new conflicts would surely erupt later—the impoverished planters would need to seize new lands from Northern settlers to survive. European immigrants in such conditions would not flock to the former USA: there’s no capital to be made, but joining any active army to divide another Nevada or Arizona would be easy. Better to go to Canada or Brazil and Argentina: there, there is no war, and there are plenty of lands and wealth.

Of course, after years of decline and discord, stability and a new rise would inevitably follow. Perhaps in the 20th century, the reconciled States would partially make up for lost time and again become magnets for migration and capital. But it would inevitably be a very different country in a completely unfamiliar world.

Main sources of the article:

● Gaivoronsky K. “Atlanta is ours!”: how President Lincoln almost lost the election and the Civil War;

● Latov Yu. New economic history of the US Civil War and the abolition of economic slavery;

● McPherson J. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era 1861-1865;

● Mal K. The Civil War in the USA;

● Popov A. Freedom granted by necessity: how the USA abolished slavery;

● Rimini R. A Brief History of the USA;

● Tippot S. USA. Complete history of the country.

Main photo — a scene from the film “Gone with the Wind” (1939)