Support the author!

The Origins of the Islamic Revolution and the Inevitability of Its Defeat

Now, with hostilities between the two states at their peak and the United States coming to Israel’s aid, it is highly likely that the chances of an uprising in Iran are slim. However, if the Iranian regime is defeated, a popular explosion of outrage will most likely indeed overthrow it. Moreover, this will happen largely for the same reasons that led to the collapse of the USSR.

At first glance, there is nothing in common between the Soviet Union and the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI). After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran has a theocratic regime where all public, political, and personal life of citizens is strictly regulated by Sharia law. The USSR, on the other hand, was an atheist country, which, by the way, provoked pathological hatred from the founder of the IRI, Ayatollah Khomeini.

However, it’s not that simple. In reality, Soviet atheism had traits of a secular religion. Its main characteristic was recently naively repeated by Vladimir Putin: there are people who believe in God, and there are those who believe there is no God, but both groups believe in something. Here Putin, of course, has an advantage — for decades he himself was a follower of this secular Soviet religion.

Scientific atheism, that is, a worldview based on scientific achievements, was only tangentially related to Soviet atheism. Religious philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev rightly noted in his work “The Origins and Meaning of Russian Communism”: “Russian atheism, which turned out to be connected with socialism, is a religious phenomenon.”

In turn, a mandatory state religion, whose dogmas must govern all aspects of society and human life, inevitably turns into ideology. This is exactly what happened after the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

Both ideologies — Marxism-Leninism in the USSR and Islamism in the IRI — converged in their key aspects. The main principle for both was national sovereignty, which in practice meant the sovereign right of their rulers to do whatever they pleased with their subjects, regardless of global public opinion. Within this principle, both states relied on ideas of national exceptionalism, uniqueness, and a glorious past.

Notably, both ideologies promised their subjects a kingdom of God on earth. And as can be seen from the example of the Islamic Republic, they partly succeeded in this.

The so-called Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran was actually one of many national revolutions of the 20th century, just heavily tinged with religious tones. Its main goal was the same as other national revolutions: the creation of an independent state.

However, the similarities between the USSR and Islamist Iran do not end there. Both countries faced similar socio-economic problems at different times, as well as similar socio-demographic processes (in Iran, albeit delayed by several decades).

The Protest Potential of the Islamic Republic

Mass protests shook the country in 2022-23 following the killing of Kurdish girl Mahsa Amini by the “Morality Police” in Iran. She was arrested on September 14, 2022, for “improper hijab wearing” and was beaten to death in a police station.

Demonstrations in memory of Mahsa Amini, spanning 16 of the country’s 31 provinces, were held under slogans like “Woman, Life, Freedom,” “Death to the Dictator,” “Morality Police — Murderers,” “I will kill the one who killed my sister,” “I swear by Mahsa’s blood,” “Iran will be free!,” “Khamenei is a murderer, his government is illegitimate,” “Oppression of women from Kurdistan to Tehran.” Thousands participated nationwide.

At least 200 people died during the suppression of these protests (some estimates say 342). Among the killed protesters were schoolgirls. The story of 16-year-old Nika Shakarami, who was abducted by security forces during protests in Tehran and tortured to death in prison, gained wide attention.

Students and teachers mainly took part in the demonstrations, but they received active support from workers at oil refineries in Bushehr and Damavand, who threatened to strike and chanted “death to the dictator.” In Bushehr, workers temporarily blocked the road to the petrochemical plant. Merchants also supported protesters by closing their shops and stalls in protest against the authorities’ actions.

In some cases, when authorities opened fire on protesters, people resorted to armed resistance. For example, on September 30, 2022, in Zahedan (Sistan and Baluchestan province), at least 96 people were shot by police during protests that erupted after news of the rape of a 15-year-old girl by the local police chief. Citizens demanding punishment for the criminal gathered near the police station and were attacked by a police helicopter from the air. In retaliation, the police station was burned down at night. Many members of the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps — one of the main pillars of the Islamist regime in Iran) were killed. State media reported 19 protesters and 32 police officers dead.

In 2009, Iran experienced the so-called Green Revolution, when despite a ban, 100,000 people took to the streets of Tehran protesting election fraud in the presidential elections. Police also opened fire to kill protesters then.

At the same time, real power in Iran belongs not to the president or parliament but to the unelected lifelong “Supreme Leader.” Formally, 88 “experts” representing the Islamic clergy can remove him from power, but in 40 years, no such precedent has occurred.

Laws in Iran are strict. The death penalty is regularly applied for acts that in normal countries would not even be considered crimes. For example, for “propaganda of obscenity” or behavior classified as “earthly debauchery,” for homosexual relations, “adultery,” prostitution, “enmity against God,” “defiling the earth.”

The use of the death penalty in Iran is among the highest in the world. The country ranks second only to China, but China’s population is roughly 15 times larger. In 2022, Iran carried out at least 553 executions; in 2023, at least 834, accounting for 74% of all executions worldwide that year (!). In 2024, the number of executions reached 901. The age of criminal responsibility in Iran is 9 for girls and 15 for boys. Executions are applied to children from age 15, including for charges like “blasphemy.” As noted above, extrajudicial killings are also regularly practiced here.

And yet, hundreds of thousands of Iranians take to the streets in protest. How is this possible in a country with an unchangeable theocratic dictatorship?

To answer this question, it is worth returning to the events of the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

Mosques versus Televisions

Today, against the backdrop of the current Israel-Iran war, hardly anyone fails to recall that Iran before 1979 was a very secular country. Tehran was called the “Paris of the East.” Many photos and videos of Iranian women of that time in European clothes, miniskirts, and swimsuits circulate on the internet.

Indeed, the then Iranian constitutional monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and before him his father Reza Pahlavi, did a lot to make their country a modern, modernized state.

From his accession to the throne in 1941 until 1949, the young Shah Mohammad hardly interfered in state governance. This was handled by a secular government under the control of the Majlis (parliament). However, after an assassination attempt by a Muslim fanatic in 1949 (he was declared a communist, and the Communist Party of Iran, called the “People’s Party,” was banned), the Shah gradually began to take power into his own hands. The secular character of the state did not change.

Iran, like many other developing countries at the time, was entering a new era. The Shah appealed to the great history of the “land of the Aryans” (the literal Persian translation of Iran’s name). But reminders of a glorious past alone were not enough.

To stand alongside the developed countries of the world, the country needed serious reforms. And the Shah’s government tried to meet the challenges of the time.

Recall that Persia from the 18th to the mid-20th century was a battleground for the British and Russian empires. Even the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s accession to the throne in 1941 was due to a coup largely carried out by British and Soviet troops brought into the country — then allies in the anti-Hitler coalition.

The reforms planned by the Shah required considerable funds. These could be obtained from the developing oil industry, then mainly under British colonial control.

Iran is the second country in the world after Saudi Arabia in proven oil reserves. A debate began over the fate of the oil fields. Some politicians advocated their nationalization; others, including the Shah himself, were categorically against it. We will omit here the dramatic story of the struggle for the Iranian oil industry, which led to political assassinations and a coup. Ultimately, control over Iran’s fuel and energy complex passed to a consortium of Western oil companies, and the country received 50% of their profits.

In 1963, the so-called White Revolution began in Iran — a set of economic reforms including land reform, nationalization of forests and pastures, privatization of state enterprises, profit-sharing among workers and employees, granting women the right to vote, and combating illiteracy.

In essence, this was a program of bourgeois revolution for a society far behind the most advanced countries of its time. In Japan, a similar reform package — the “Meiji Restoration” — was launched in 1868 (also, by the way, under a monarch’s aegis).

The land reform of the Iranian “White Revolution” involved forced purchase of land from Iranian feudal lords and subsequent sale in small plots to 1.5 million peasant households at prices 30% below market value. Peasants were given preferential loans with very low interest, repayable over 25 years.

Privatization of state enterprises was also progressive, especially given Iran’s semi-feudal system at the time, where “state” property actually belonged not to the state as a whole but to the specific ruler — the Shah. Enterprises passed to bourgeois (or, as we would say now, efficient) owners. To reduce capitalist exploitation costs, workers and employees were to receive 20% of profits from the new private companies, plus bonuses for increased labor productivity and reduced production costs.

Women’s suffrage was undoubtedly also a huge step forward.

However, the generally progressive reforms of the government caused problems and dissatisfaction not only among representatives of the old order — landlords and clergy — but also among broad layers of Iranian society.

For example, the Shah widely opened doors for agricultural imports, which hit the Iranian agricultural sector hard. New small, poorly mechanized peasant farms could not compete with cheap imported products and went bankrupt en masse. Moreover, land did not reach all peasants. One member of a large Iranian family became the landowner, while his brothers had to seek their fortune in the city.

Thus, millions of ruined young Iranian peasants with their archaic worldview, where loyalty to tradition and Islam was paramount, flooded into cities. Primarily into prosperous Tehran, whose central streets looked as if they had come straight from glossy magazines about Western life. But even in Tehran, many of these young people, deprived of everything and often uneducated or simply illiterate (the illiteracy rate in Iran among those aged 15 and older in 1976 was about 64%), could not find decent jobs or means of subsistence, swelling the lumpenized population of the prosperous capital.

“Rapid economic growth was not balanced, and was accompanied by extremely high economic inequality... The gap grew rapidly not only between city and countryside but also between rich and poor neighborhoods within cities. Northern Tehran reached a very high, Western European standard of living, while many districts of Southern Tehran lacked not only infrastructure but even basic housing conditions. A colossal gap was also observed between the capital and the rest of Iran: by the mid-1970s, less than 20% of Iranians lived in Greater Tehran, but it concentrated 42% of hospitals, 50% of doctors, 66% of students, and about 70% of car owners.”

Opponents of the Shah among conservatives campaigned against his policies primarily in mosques, since poor peasants and workers from the southern outskirts of Tehran living in slums had no televisions. Mullahs explained to them that all their troubles stemmed from the rampant corruption around them, which was itself the result of forgetting the glorious traditions of the past and religion.

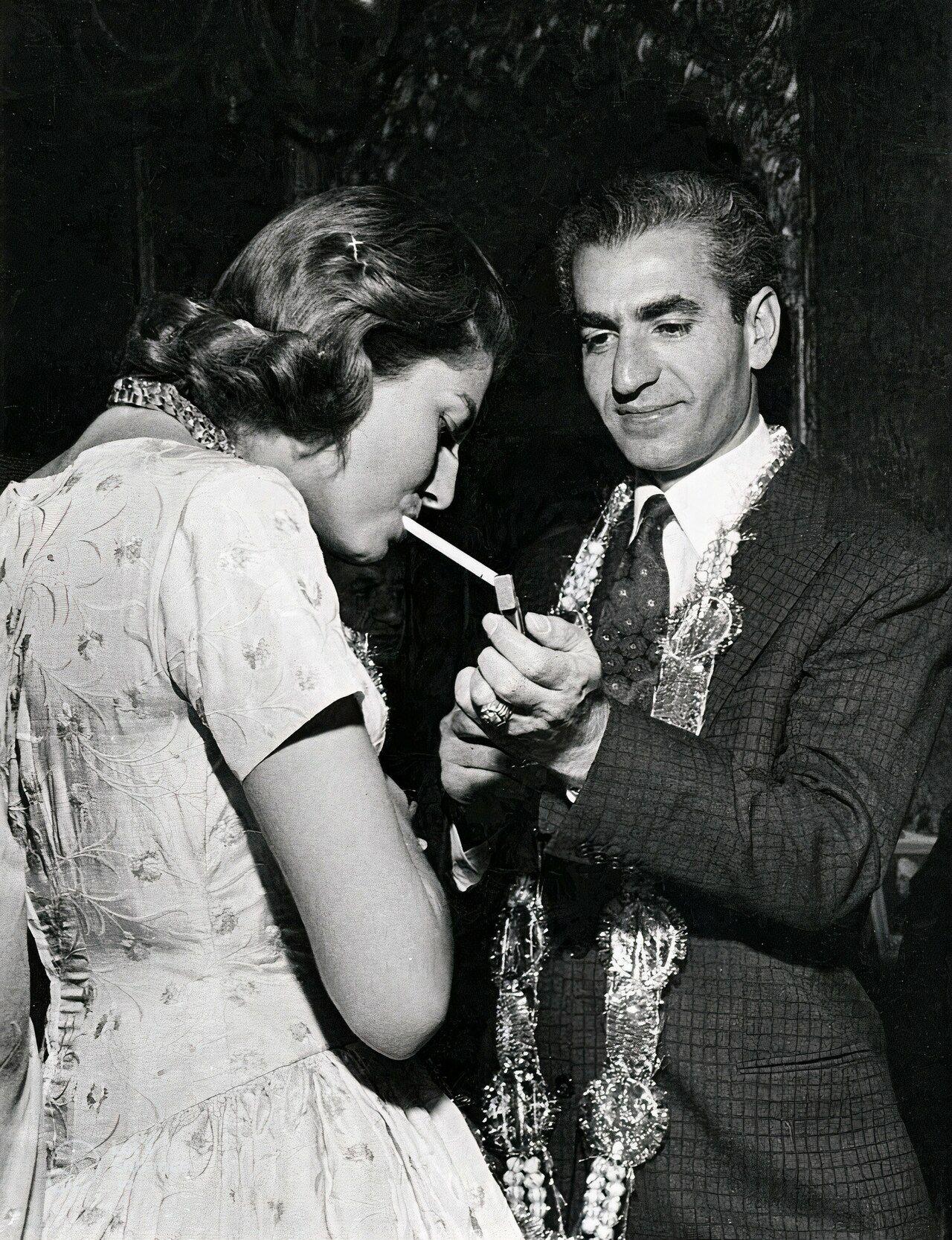

Meanwhile, the Shah and his close circle indulged themselves in everything. For example, the wedding dress of Mohammad Pahlavi’s second wife Soraya was made of 900,000 gold grains, 20,000 marabou feathers, and 6,000 diamonds. The dress was so heavy that, contrary to tradition, its train had to be carried not by girls but by adult women, and the bride nearly fainted.

At the same time, the state spent huge sums on military expenses. From 1954 to 1977, they increased 120-fold (!) — from $60 million to $7.2 billion in 1977 (1973 prices).

The relations between Shah’s Iran and Israel were friendly, which was also a reason for accusations against Mohammad Pahlavi by Islamic orthodox circles that he was a protégé of the “Zionists.”

At the same time, the secret police SAVAK, created in 1957 with the help of the CIA and Mossad, flourished. In 1973, all political parties were banned in Iran, and in 1975, a single ruling party, Rastakhiz, was established.

Authoritarian tendencies in the Shah’s policy increased. In the mid-1970s, he announced an ideological trinity: “God, Shah, and Homeland” (very much like “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality” in Nicholas-era Russia). At the same time, Pahlavi proclaimed himself the successor of all previous Persian dynasties.

The oil boom triggered hyperinflation in the early 1970s and a prolonged economic crisis, worsening the situation of those already in dire straits — primarily peasants and urban lower classes.

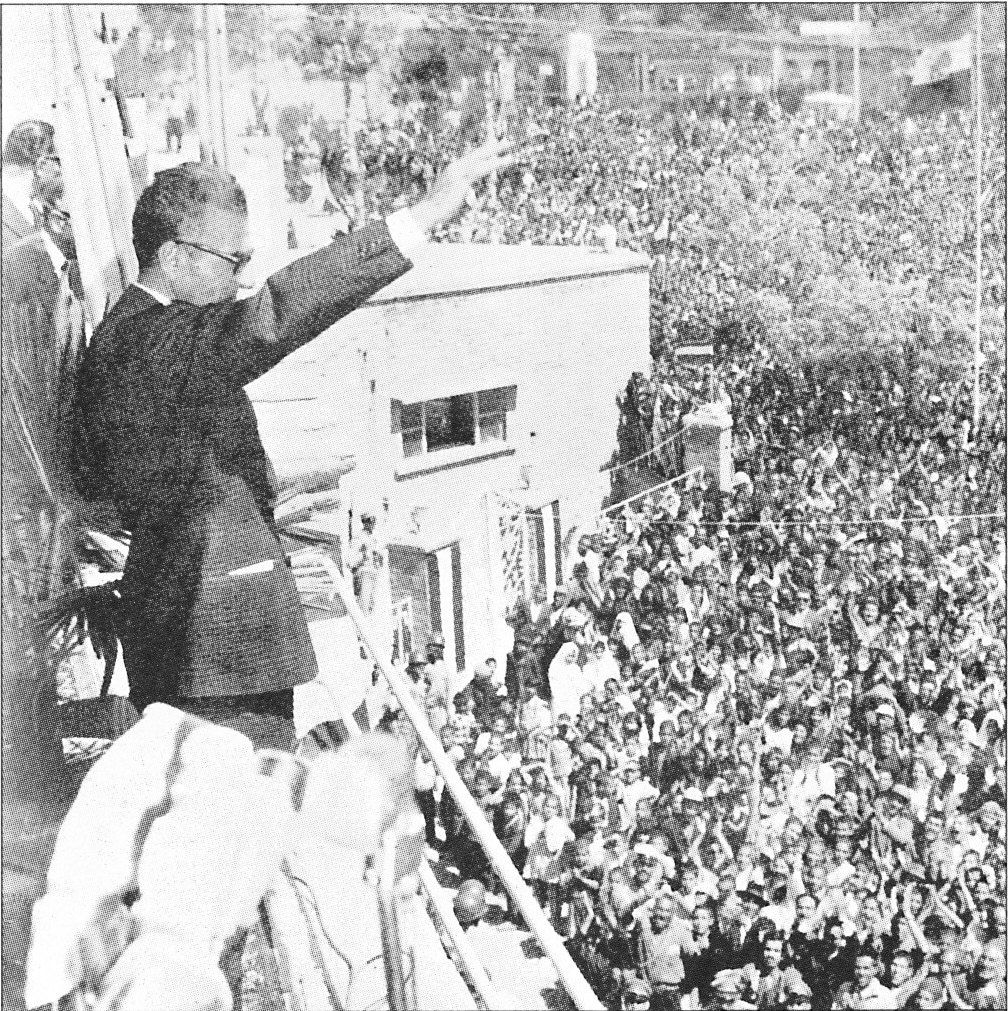

It is no surprise that on February 1, 1979, millions took to the streets of Tehran to welcome the nation’s new savior — Ayatollah Khomeini, who returned from 15 years of political exile.

After the Islamic Revolution

With the victory of the Islamic Revolution, Iranian society suffered a monstrous regression to medieval times. However, this phrase does not fully capture what happened in the country. After all, even in Iranian medieval times, there were periods much freer than Khomeini’s theocratic dictatorship.

However, after the establishment of the mullahs’ dictatorship, for their own survival they had to solve a number of social and economic problems. Their logic was similar to that of the hated Soviet leaders under Khomeini.

For their survival, they needed a modern army — and accordingly, a modern, as independent as possible from other countries, military-industrial complex. Creating the MIC required many educated people — engineers, scientists.

To train such personnel, modern secular scientific and technical education (universities) was needed. For producing and operating modern equipment — mass primary, secondary, and vocational education (schools, vocational schools, technical colleges).

For the accelerated industrialization Iran needed then, many workers were required. The countryside could and did provide these at that stage. This, in turn, meant fairly rapid urbanization. The urban population increased, the rural population decreased. For example, in 1976, urban population was 47%, rural 53%; by 1986, the proportions changed to 54.3% urban and 45.7% rural.

According to the 2016 census, Iran’s urban population rose to 74%, comparable to highly and moderately developed countries such as Russia. The only difference is that this percentage of urban residents in Russia has remained almost unchanged for about 40 years.

The average level and quality of life in Iran rose significantly — both in cities and in rural areas.

For example, in 1977, only 22.6% of city dwellers and 3.2% of villagers had televisions; by 1984, televisions were in 79% of urban and 25.6% of rural households. By 2004, these figures were 97.5% and 89.1%, respectively.

In 1977, refrigerators were used by 36.5% of city dwellers and 7.6% of villagers. By 2004, 98.5% of urban and 92.4% of rural residents had them.

Telephones were in 21.3% of city households in 1984 and 81.2% in 2004. In rural areas, usage was 0.4% in 1977 and 49.4% in 2004.

Electricity was almost universal in cities by 1984 — 99.5%, and 100% by 2004 (in rural areas, 57.1% and 98.3%). Clean drinking water was available to 96.2% of urban and 43.9% of rural residents in 1984, and to 99.1% and 89% respectively in 2004.

As of 2011, 18% of Iran’s population had higher education. There is no more recent data, but considering that higher education in Iran is free (though there are commercial universities) and the government encourages its citizens to obtain it according to the constitution, it can be assumed that today this figure is no less than 20%.

For comparison: in the Soviet Union two years before the August 1991 revolution, only 11% of the population had higher education.

All this indicates that

the mullah regime in Iran, guided partly by ideology and partly by pragmatic considerations of survival, like the ruling class in the USSR once, has itself nurtured its gravedigger — a modern educated urban middle class.

Once established, this new class always begins to demand from the aging ruling elite the return of its rights: freedom of speech, thought, assembly, association, public and private life. Ultimately, power itself.

Now, these demographic and social processes in Iran are compounded by war. If Iran loses, the fate of the theocratic regime will be sealed.

Main photo — Iranian Revolution 1978-1979. Protesters carry the body of one of the dead, 1978. Photo: Public Domain